What was the ark of the covenant? You’ve heard of it. You’ve read of it. Maybe you even saw it in Raiders of the Lost Ark. But what was it really? What did it look like? And why was it so important?

In the desert, after the Exodus from Egypt, the Lord told Moses to make a ceremonial ark or aron – a wooden chest – as a sign of the covenant made at Mount Sinai.[1] The ark was made of acacia wood—a box within a box within a box—a metre long, and overlaid with gold.[2] On top was a solid-gold cover called the kapporet, where two golden keruvim or ‘cherubim’ faced each other, wing-tips touching.

WHAT IS A KERUV?

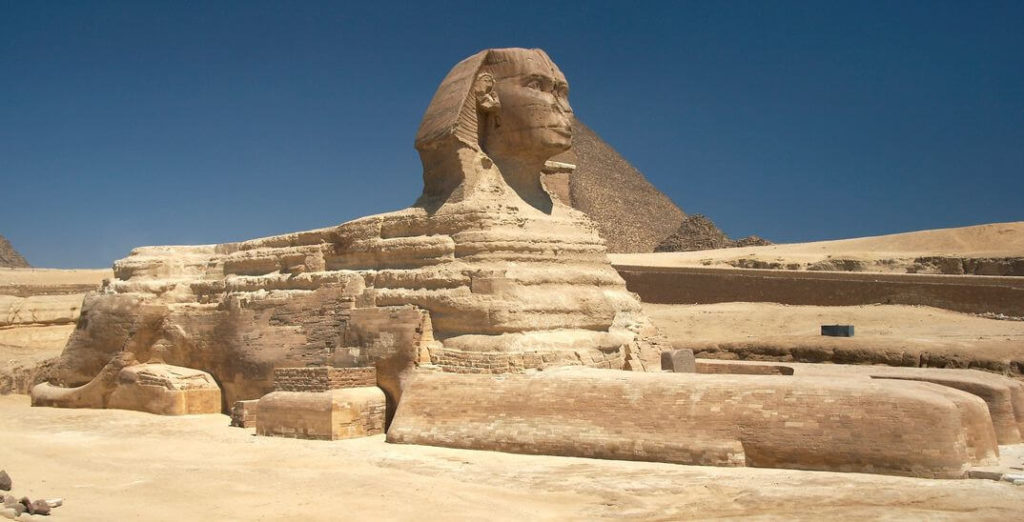

The keruv or cherub is a being whose general type is well known to us from ancient eastern iconography. It was not a winged man; much less a little flying putto or baby boy. Rather it was a being combining human characteristics with those of fierce animals and birds, and representing a solar or stellar deity. The best-known example is the great man-headed lion the ancient Egyptians called Re-Hor-Akhty – ‘Ra-Horus of the two horizons’ – better known nowadays as the Great Sphinx of Giza.

Photo by Barcex (Wikimedia commons)

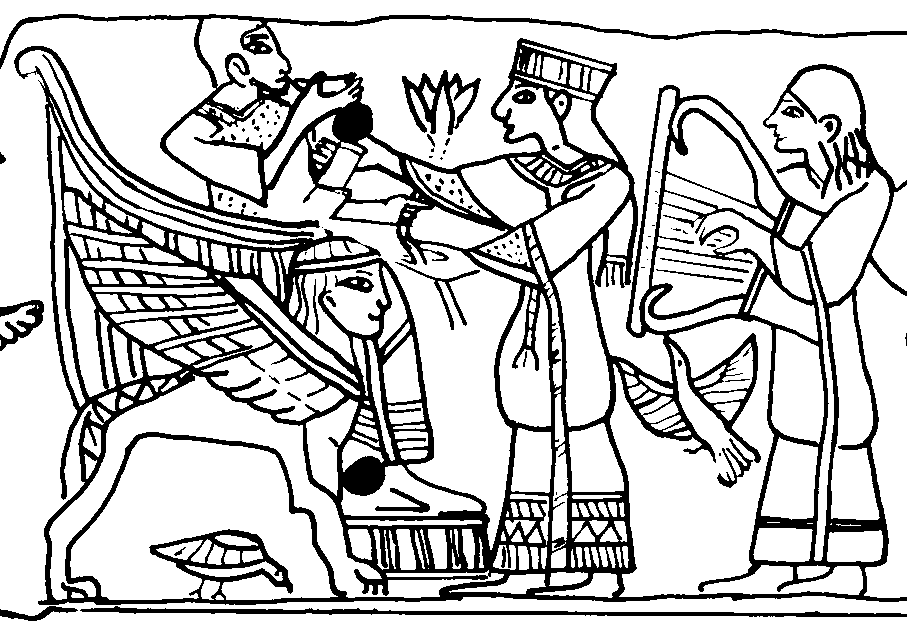

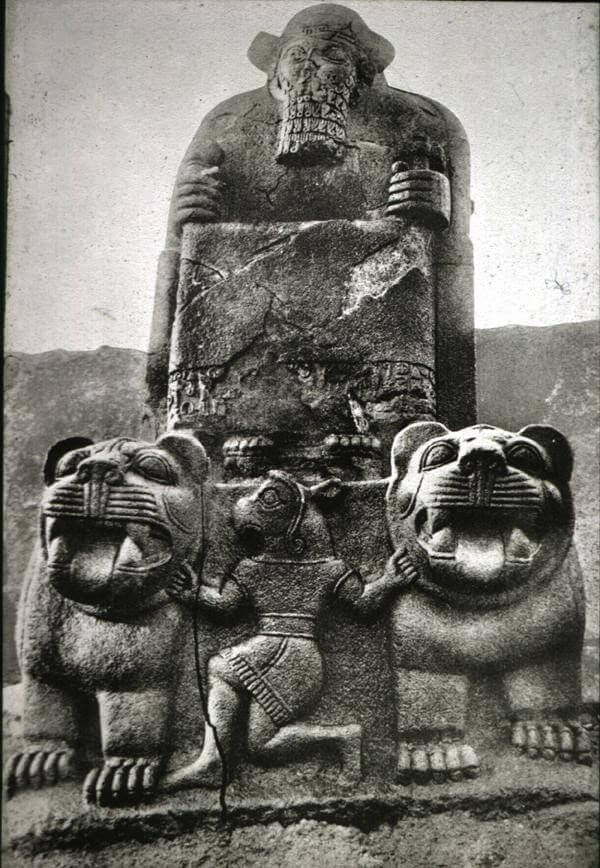

And while the Egyptians do not seem to have had a generic name for such creatures – ‘sphinx’ is a Greek word – they had many of them, winged and wingless. King Tut-ankh-amun’s throne is upborne by winged sphinxes. Further eastward, the Levantine sphinx or lamassu is routinely a winged man-headed bull or lion. The king of 13th century BC Megiddo sits on a throne supported on each side by lion-bodied lamassu: stellar deities to attend a heavenly king. He sips his wine, unaware that the sword of Joshua is raised to cut him from his celestial throne.[3]

The ‘Ain Dara temple in northern Syria, which stood from about 1300 to 740 bc, has man-headed, eagle-winged, bull-bodied lamassu on each side of the entrance. Similar images were made in Assyria, to Israel’s north-east. Two colossal winged man-headed lions, from the entrance to the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) at Nimrud are preserved in the British Museum. Colossal man-headed bulls, from Ashurnasirpal’s palace and from the palace of Sargon II in Khorsabad, can also be seen there.[4] Further east, Persian sphinxes featured the head of King Darius upon the lion body.

The Israelite keruv must have shared similarities with its ancient counterparts, but it had distinctive features of its own. The keruvim seen by Ezekiel, for instance, have the form of a man, with calves’ feet, human hands, four wings, and four faces; the faces are those of a man, a lion, a bull, and an eagle; or alternately, of a man, a lion, an eagle, and, yes, a keruv.[5]

Israelite artisans apparently knew what keruvim –even their faces – looked like. After all, they embroidered and carved their images throughout Moses’ Tabernacle and the temple. But no image of Israelite keruvim has survived to this day. Yet, like sphinx or lamassu, Israel’s keruvim were guardian deities, manifestations of heavenly bodies, waiting upon the divine king. Given Israel’s cultural and geographical proximity to Canaan, it is likely that the keruvim of Moses’ and Solomon’s time resembled the creatures flanking the Megiddo throne.

HOW WAS IT CARRIED?

The ark was carried by means of gold-plated acacia poles which ran along the sides of the ark, inserted in the rings attached to its feet; these poles were a permanent feature of the ark and were not removed from their rings.[6] Inside the ark, beneath the kapporet cover and the keruvim, Moses placed the two stone tablets of the ten commandments – Israel’s covenant obligations to their divine king – together with Aaron’s staff and a jar of manna. The ark, borne aloft on the shoulders of the Kohathite Levites, accompanied the Israelites through the wilderness, thrice-shrouded from prying eyes beneath coverings of sanctuary curtain, dugong skins, and cloth of heavenly blue.[7]

The Israelites also made a magnificent tent, the Tent of the Tabernacle of Meeting to house the ark when resting. (This ornate tabernacle should not be confused with the simpler Tent of Meeting set outside the camp.[8]) Inside the great Tabernacle, once a year, the blood of the sacrifice of atonement was sprinkled upon the kapporet, so that the Holy One, looking to the commandments beneath, might see the atoning blood and pardon his people.

WHAT DID THE ARK OF THE COVENANT REPRESENT?

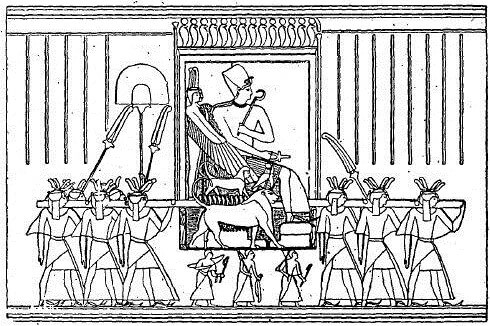

What did this artifact represent? Some suggest that it represented a portable throne for the deity. Such an idea finds support in the ancient prototypes that lay behind Moses’ ark, not only the thrones of Tut-ankh-amun and Megiddo but also the sphinx-palanquins in which the Pharaohs were borne forth, like this one where Ramses III has lion-keruvim on either side.

Various Bible verses in English translation initially seem to support this idea.

The ark of the covenant of the Lord of hosts enthroned upon the keruvim (1 Sam. 4.4).

The ark of God which is called by the name, the name of the Lord of hosts enthroned upon the keruvim upon it (2 Sam. 6.2).

Lord God of Israel, enthroned upon the keruvim (2 Kgs 19.15).

Lord of hosts, God of Israel, enthroned upon the keruvim (Isa. 37.16).

O One enthroned upon the keruvim, shine forth (Ps. 80.1).

He sits enthroned upon the keruvim; let the earth quake (Ps. 99.1).

It was perhaps such an understanding of the ark that led the King James Bible to translate kapporet – the ark cover – as ‘mercy seat’. But the Hebrew and Septuagint Greek terms, kapporet and hilasterion, contain no idea of a seat. They speak rather of atonement, of the place where the atoning blood was sprinkled. And indeed, the whole idea of the Holy One sitting on the ark is suspect. For why would one sprinkle blood on a seat? And while a one-metre-wide seat might be fine for a man, it suggests a smallish deity. Nor do these phrases contain any Hebrew word meaning ‘on’ or ‘upon’. In fact, the verb yashav, above translated as ‘sit enthroned’, can also mean ‘dwell’. A neutral translation would be as follows.

The ark of the covenant of the Lord of hosts dwelling the keruvim (1 Sam. 4.4).

The ark of God which is called by the name, the name of the Lord of hosts dwelling the keruvim upon it (2 Sam. 6.2).

Lord God of Israel, dwelling the keruvim (2 Kgs 19.15).

Lord of hosts, God of Israel, dwelling the keruvim (Isa. 37.16).

O One dwelling the keruvim, shine forth (Ps. 80.1).

He dwells the keruvim; let the earth quake (Ps. 99.1).

This more neutral translation allows us to see the two passages from Samuel as somehow representing the Lord ‘dwelling’ the keruvim on the ark, without being actually seated upon them. What would this mean? Well, let us begin with the last four texts. They date from temple times, and one may therefore suspect that they are not speaking of the keruvim upon the ark at all. Rather, they are speaking of the great golden chariot of the keruvim that spread their wings, which David planned and Solomon built in the holy of holies.[9]

David’s golden keruvim-chariot was designed as the earthly counterpart of the divine chariot-throne on high, from which the Holy One rode out across his heavens. David believed that Israel’s God rode forth on a chariot to defend him (Ps. 18.10). But this idea neither began nor ended with him. Its roots lay in Mesopotamian beliefs of the third millennium bc, and it flourished later in the chariot visions of Elijah, Elisha, Ezekiel, and the medieval kabbalists.[10] So David, under the guidance of the divine spirit, designed a keruvim chariot-throne for the invisible deity who would dwell in the house in Jerusalem. And beneath it, under its overspreading wings, was the place of the ark.

WHAT WAS THE ARK OF THE COVENANT

Therefore a likelier explanation altogether is that the ark represented the footstool of the Holy One. In this sense, he could remain or dwell upon the ark, as in the texts from Samuel, for his feet rested upon it. For the footstool, like the sceptre and crown, is a perennial symbol of royal estate. The king puts his royal feet up, while others attend him, standing in the dust. No self-respecting monarch goes without one. Tut-ankh-amun had a footstool. The king of Megiddo, shown above, has a footstool. The kings of Israel had footstools.[11] Even in 1953, Great Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II was crowned with her feet on a footstool. And so the ark was the footstool of the Lord. We find this in the same passage of Chronicles that speaks of the keruvim chariot.

I had it in my heart to build a house of rest for the ark of the covenant of the Lord, for the footstool of our God (1 Chr. 28.2).

We find it also in the Psalms, including one of the Songs of Ascents:

Extol the Lord our God and worship at his footstool (Ps. 99.5)

Let us go to his dwelling place and bow down at his footstool.

Arise, Lord, to your resting place, you and the ark of your power (Ps. 132.7).

We find it too in the prophets, in Isaiah, where the Jerusalem sanctuary (where the ark sits) is the place of the Holy One’s feet, and in Lamentations, where he spurns his footstool, the ark, in the day of Jerusalem’s devastation.

The glory of Lebanon will come to you,…

to adorn the place of my sanctuary;

and I will glorify the place of my feet (Isa. 60.13).

He has not remembered his footstool in the day of his anger (Lam. 2.1).

The idea of the ark as a footstool is confirmed by other ancient texts which show that a covenant or treaty was placed in a chest beneath the feet of the god who served as witness to it. Ramses II, making a treaty with the Hittite king Hattusil, wrote to him as follows:[12]

The writing of the treaty which I have made to the Great King, the king of Hattu, lies beneath the feet of the god Teshup: the great gods are witnesses of it. The writings of the oath which the Great King, the king of Hattu, has made to me, lies beneath the feet of the god Ra: the great gods are witnesses of it.

In the same way, the ark was a footstool, and Israel’s covenant obligations – the commandments within – rested under the invisible feet of Israel’s deity.

Seeing the ark as a footstool may help us better imagine what it looked like. The keruvim and their wings would not enclose all sides of the ark, as is sometimes depicted. Rather, the keruvim at the ends of the ark would have touched each other with one raised wing-tip each on one long side, while their other wing would have been lowered and not touching, so forming a periphery of keruvim wings and bodies on three sides of the ark, but leaving one long side of the cover open to receive the feet of the invisible king.[13] Indeed, it may be that the keruvim were not entirely located on top of the golden cover. It is more likely that, like the Megiddo throne, their heads, bodies and wings rose on the cover on three sides, while their legs and feet formed the feet of the ark itself (Exod. 25.12).

Finally, here is a statuette from Carchemish in Syria, dating from around the same time as Solomon’s temple, which may help to give a sense of the structure of the ark and of the keruvim chariot in the holy of holies. The Hittite storm-god Atarsuhis rides forth to battle on a great lion-headed chariot. Between the lion-keruvim, his feet rest on a footstool.

Thus the gods of the ancient east went forth to war. In the same way Israel’s God in his throne room sat on a chariot of keruvim, attended head and foot by these heavenly beings, ever ready to go forth, as the prophets depict him, his footstool borne aloft by his earthly ministers, to save his people and execute judgment upon the earth.[14]

This post is an extract from Chapter 5 of my book, The Songs of Ascents (2015).

| What is the Ineffable Name of God? | What happened to the ark of the covenant? | Where is the ark of the covenant? (No, really!) |

NOTES

[1] Exod. 25.10–22; 37.1–9. The ark’s having the same name as Noah’s boat derives from Tyndale, who employed English ‘arcke’ – a wooden vessel – for both. But the Hebrew words are as different as the objects themselves. The sacred chest is aron; Noah’s boat is tebaḥ.

[2] For the ark’s three-shell construction, see B. Yoma 72b. The kapporet sat upon the inner boxes, and lay within the outer one.

[3] Other depictions of a king on a keruvim throne, dating from 1200 to 800 B.C., have been found at Byblos (King Hiram) and Hamath. See Albright 1961: 96.

[4] The bull-lamassu are each one of a separated pair, with their original twins in the Metropolitan Museum of New York and the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago. Sargon’s lamassu weigh over forty tons.

[5] Ezek. 1.5–10; 10.14.

[6] Exod. 25.15. For the poles being on the short sides of the ark, see Appendix II.

[7] Num. 4.4–15.

[8] The first Tent of Meeting (ohel mo‘ed), outside the camp,is described in Exod. 33.7–11; 34.34–35. The ark’s Tabernacle of Meeting (mishkan mo‘ed) was built after it (Exod. 36.8–38; 39.32-43) and superseded it, as is implied in the repeated use of ‘Tent of Meeting’ and even ‘Tent of the Tabernacle of Meeting’ (ohel mishkan mo‘ed) to describe the newly-built Tabernacle (cf. Exod. 40.2, 6, 29, 34, 35).

[9] 1 Chr. 28.18; cf. 1 Kgs 6.23–28; 2 Chr. 3.10–13.

[10] Chilton 2011: 20.

[11] Ps. 110.1; 2 Chr. 9.18.

[12] Text from De Vaux 1961: 301.

[13] Likewise Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1386–1349 BC) is shown seated upon a throne with sphinx side-arms (see Plate 111 in G. Steindorff und W. Wolf), as is King Ahiram on a stone sarcophagus from 12th century BC Byblos. All these kings, incidentally, are drawn with footstools.

[14] Ps. 18.10; Ezek.1.4–28; 10.9–22, where the wheels of the chariot, the ofanim, are heavenly beings; Dan. 7.9; Hab. 3.8, 13.