THE LORD’S PRAYER IN ARAMAIC

JESUS originally taught the Lord’s prayer in Aramaic. But how did that sound? Can we learn to say it in Aramaic too? Or sing it according to its melody sung in the churches of the east? You can read all about it here…

JESUS SPOKE ARAMAIC

Jesus taught the Lord’s prayer to his disciples in the Aramaic language. This comes as a surprise to some folk who think Jesus taught in Hebrew or in Greek. But all the evidence is that Aramaic was Jesus’s own tongue. The story of Aramaic is a big story. Although it now has very few first language speakers, it was once one of the greatest languages in the world. As the language of the Assyrian empire, it went from being a tribal language of Syria to becoming the lingua franca of the entire east—from Egypt to India—in the period 700 BC to 200 AD. As a result, we now know it by many names—not only Aramaic, but Syriac, Chaldean, Osroenian, and Assyrian.

Because of this expansion, Aramaic became the language of the ordinary people of Galilee in the time of Jesus. And, of course, Jesus was a Galilean. And so, in the gospels, the little phrases that Jesus speaks from time to time in his own language—Ephatha or talitha qum—are Aramaic.

Of course, Jesus knew Hebrew and Greek well too. There is evidence that he spoke Hebrew (or Hebraeo-Aramaic) sometimes. For instance, he says, “If your eye is good your whole body is full of light. But if your eye is evil, your whole body will be full of darkness” (Matt. 6:22-23). This really makes sense only in Hebrew. A “good eye” and a “bad eye” is a Hebrew way of saying a generous or ungenerous spirit. But it doesn’t have the same sense in Aramaic or Greek. In fact, in Aramaic, the “evil eye” is the power of a sorcerer, which isn’t the meaning here. And we know Jesus spoke Greek. Almost everyone in first-century Israel spoke Greek just like almost everyone in modern Israel speaks English. Greek was the language of the Mediterranean world after the time of Alexander the Great.

ARAMAIC—THE ANCIENT LANGUAGE OF ISRAEL

But Jesus’s default language, the language of his heart, was Aramaic. You might think that is strange. Surely the son of God should have Hebrew as his first language. But it’s not so much a departure as a return. Remember, Aramaic was also Abraham’s native language. Moses even taught the Israelites to say, “My father was a wandering Aramean” (Deut. 26:5). So Aramaic is an ancient and authentic language of the Israelites. So there is really no surprise that the son of God should take it as his own.

Like I said, Aramaic was the language of Galilee. That means that when Jesus spoke to his disciples, he spoke Aramaic. And when he spoke to the crowds beside the Lake, he spoke Aramaic. And when he spoke in their synagogues, he spoke Aramaic (but read the scriptures there in Hebrew). It follows then that when he taught the Lord’s prayer, he taught it in Aramaic.

THE OLD ARAMAIC TEXTS OF THE LORD’S PRAYER

By the early Christian period, the form of Aramaic spoken in the Levant was called Syriac, while, east of the Euphrates, it was called Osroenian. Today, we use this term, Syriac, to refer to the form of Aramaic used by the old churches of the east. Meanwhile, we tend to use “Aramaic” to refer to “Imperial Aramaic“, the classical Aramaic spoken in the Persian empire, which features in the Book of Daniel, or, in a later form, for the language of the targums, the Jewish Aramaic translations of the Bible. There are many different versions of Aramaic. But Syriac has a cursive script, a bit like Arabic. But when we speak of “Aramaic” we usually mean the version of the language using the square letters familiar to us from Hebrew. (In fact, these square letters were originally Aramaic. During the Babylonian exile, the exiled Judeans adopted them and neglected their own Paleo-Hebrew, or “Libona’a” alphabet.) Linguistically, Aramaic sits halfway between Hebrew and Arabic, just like Dutch sits halfway between English and German.

The most ancient Syriac-Aramaic gospels are now called the Vetus Syra or Old Syriac texts. Only two representative manuscripts survive. One, from the Library of the Convent of St. Mary Deipara in the Natron Valley of Egypt, is now called the Curetonian text. The other, discovered by discovered by Agnes Smith Lewis in Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai in 1892, is called the Sinaitic Syriac text.

However, the everyday Aramaic Bible of the Aramaic-speaking churches of the east is the Syriac Peshitta. (Peshitta means “plain” or “simple”.) It’s hard to be dogmatic about the exact date of the Peshitta New Testament. There are no truly ancient texts of it in existence. The Peshitta text, as it now stands, probably dates from the late fourth or early fifth century. But, as said, the Curetonian and Sinaitic texts are older. And the Church Fathers speak about the existence of Syriac gospels in the second century AD. Scott Callaham speaks in this Daily Dose video about how the

NO SINGLE TEXT

It follows that the closest we will get to the exact words of Jesus is in these old Aramaic texts of the Lord’s prayer. But they do not always agree. For instance, the Curetonian text, says Your will be done on earth as in heaven. That’s the same word order as in the Greek versions of the gospels. But the Peshitta text says Your will be done as in heaven so on earth. So, in this case, it looks like the older Curetonian text is the original, for it resembles our Greek New Testament text. Scott Callaham also points out in this Daily Does video (starts at 23:19) that the Peshitta text is older than the Greek text of Matthew because it closes with the doxology (Thine is the kingdom) which isn’t found in the earliest versions of Matthew. And the same is true of the Curetonian text and the Vetus Syra, whose Matthew text looks like a copy of the Curetonian. In general, the Curetonian seems oldest, then the Vetus Syra, and then the Peshitta. And it’s likely that none of them contain the exact words of Jesus, yet all of them reflect maybe 85% or 90% of Jesus’s words. The only way you could be sure of the 100% original text would be if you had been present at the Sermon on the Mount.

For now I’m going to concentrate on the Peshitta. It’s not the oldest text. But it is the accepted Bible of the churches of the East. On that basis, it deserves our attention. If you want to know a bit more about the older Syriac texts, see the links at the end of this blog.

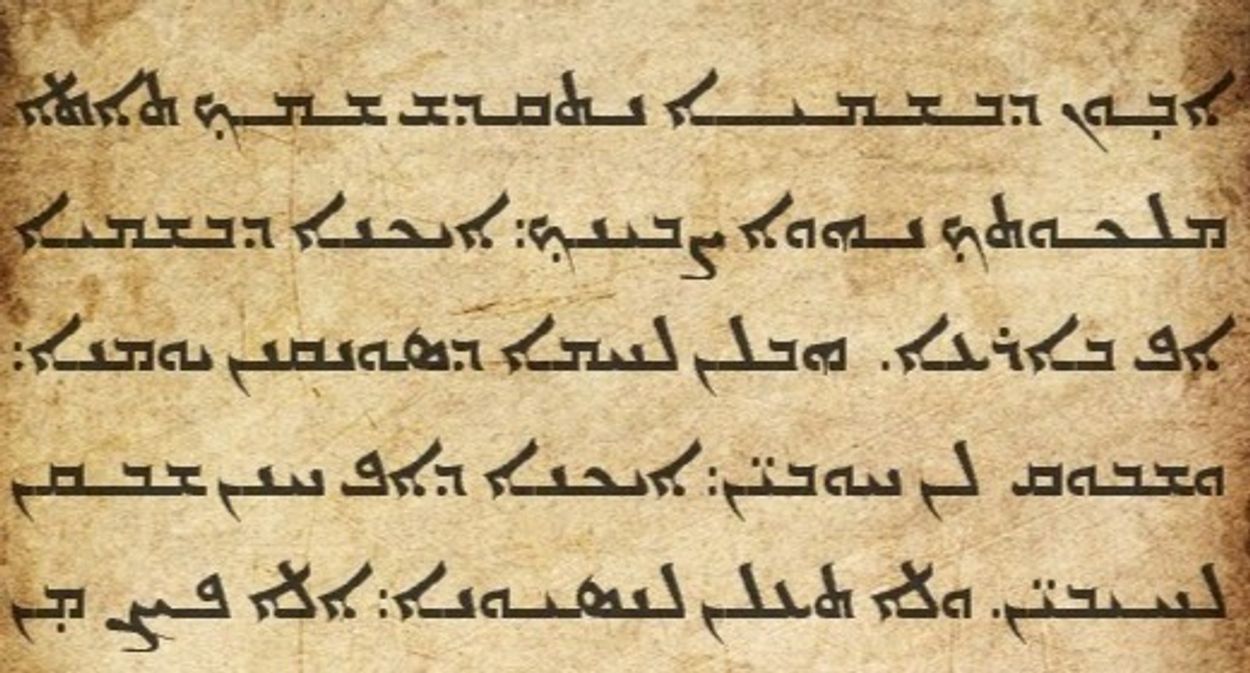

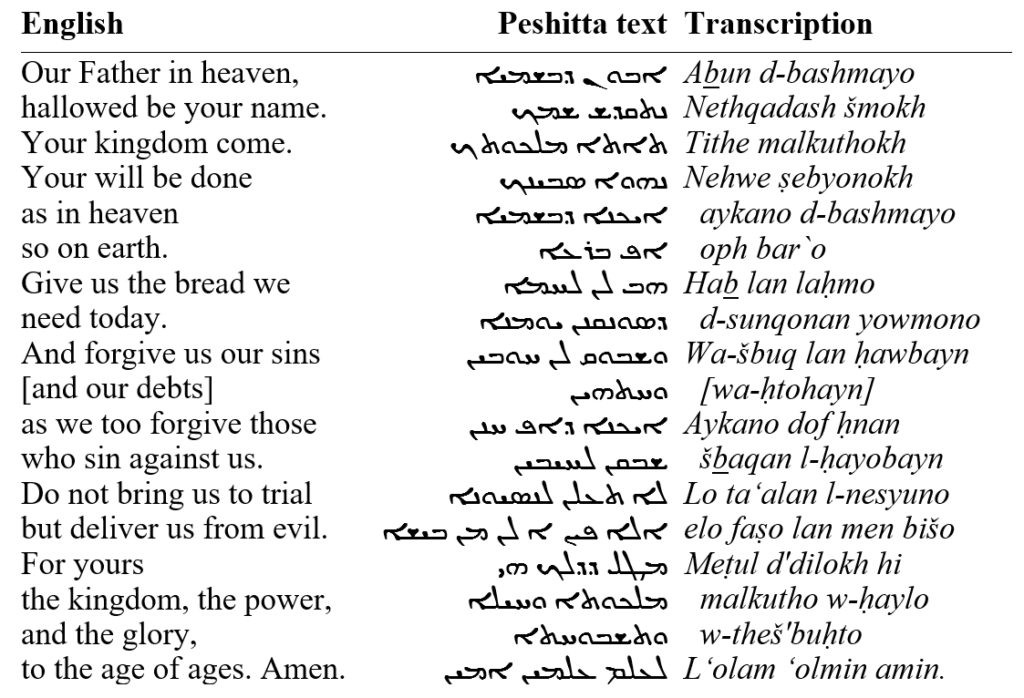

Here is the Peshitta text of the Lord’s prayer in Syriac with a transcription. The words in brackets—and our debts—are an addition found in the sung version of the prayer, as described below.

AN OLD MELODY FOR THE LORD’S PRAYER

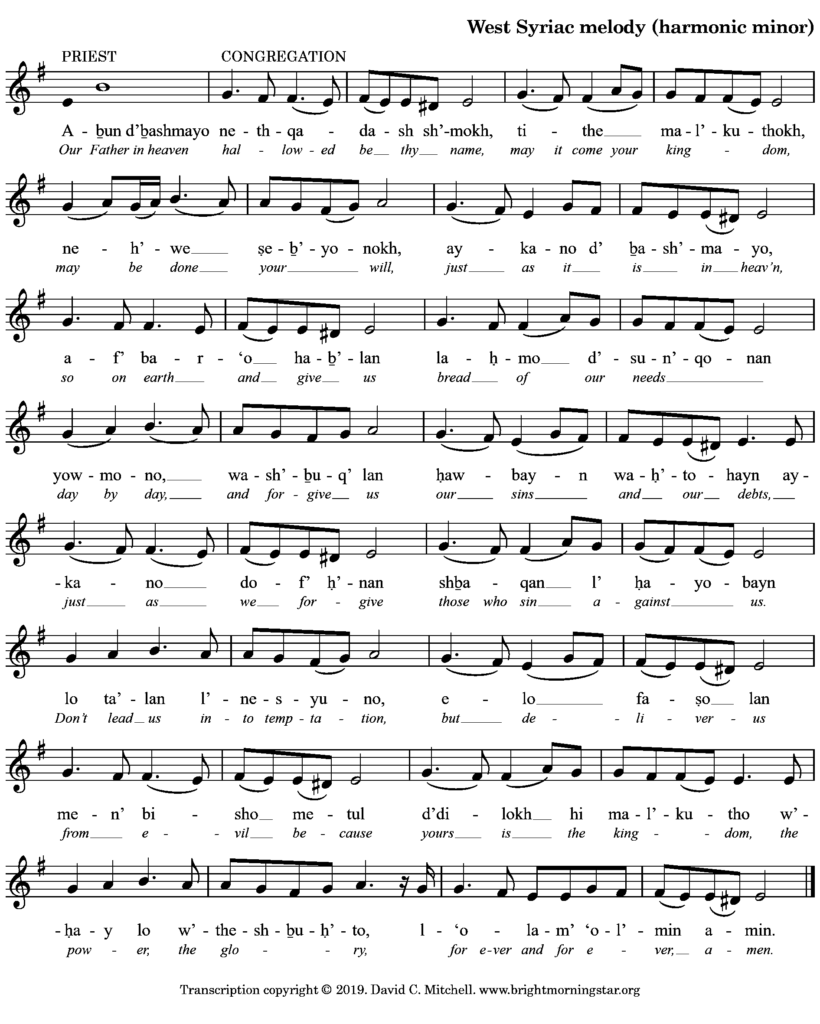

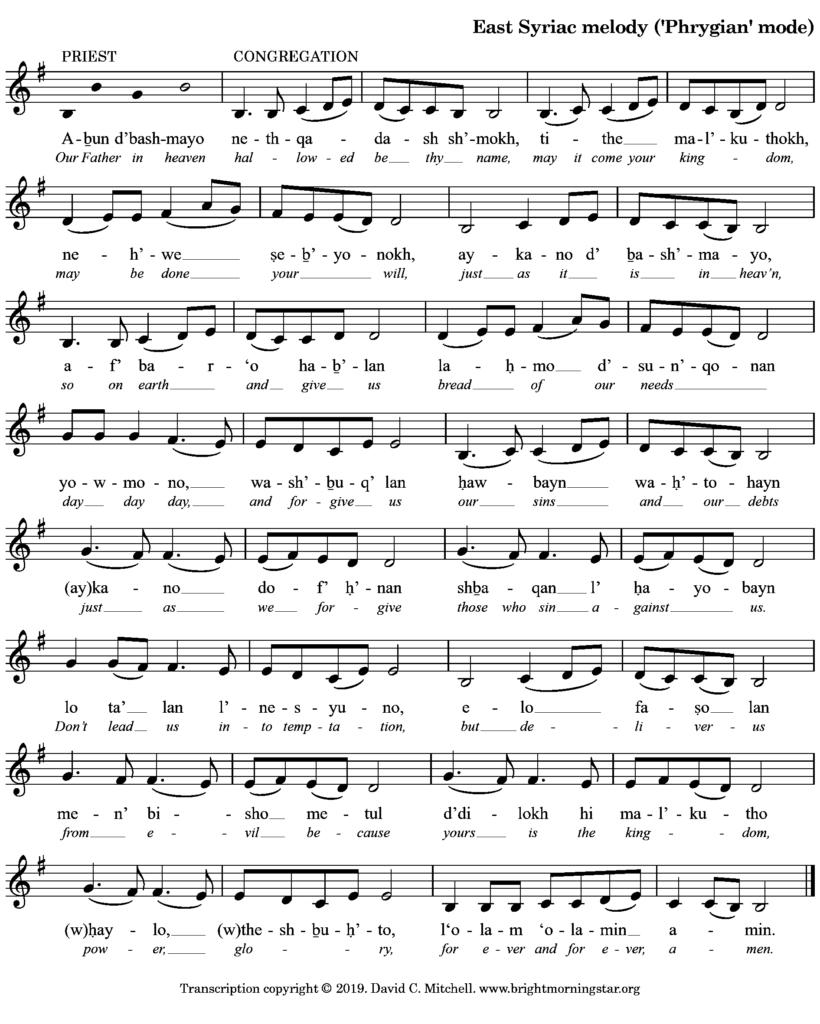

The churches of the east have sung the Lord’s prayer since ancient times. And they have different versions of the melody for it. I say the melody because both versions fit the words to the same rhythm in the same way. But the west Syriac churches (in Syria and Palestine) sing it to a harmonic minor melody, while the east Syriac churches (in Iraq) sing it to a melody in the Phrygian mode.

Personally, I think this sung version of the prayer is well worth learning so you can speak or sing the words which Jesus taught his disciples. In my house, we sing it en famille once a week, on Sunday evening. And now my kids can sing it by heart. I think that is a beautiful thing for them to have learned while they are still young.

If you’d like to know more about what the Lord’s Prayer can do for you in your day to day life, then you might like this book, How To Be Happy For Ever (No, Really!!). Who knows, it might turn your life around.

Here are both versions with links to recordings on Youtube.

WEST SYRIAC MELODY

Here is Lina Sleibi singing it in the Catholic Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. Brava, Nina! I’m a huge fan!

EAST SYRIAC MELODY

And here is the melody as they sing it in the Syriac-speaking churches of the east. As I said, it’s in the Phrygian mode. Plato called this the noblest of all the modes (Republic III: 398-400). But Plato actually called it the Dorian mode. (That’s what the ancient Greek music theorist Aristoxenos called it. But the Swiss musicologist, Henricus Glareanus, mixed up the two modes in the sixteenth century, and they have been called by each other’s name ever since.) So it’s in the “Phrygian” mode of B. Watch out for those C naturals!

Here is the east Syriac melody, as sung in Iraq. In the first video, there is no incipit (abun d’bashmayo), and the singing starts at 1’35. The second video has the incipit (Abun d’bashmayo), and the singing, by Father Tony Kasih, starts at 0’57.

THE ARAMAIC TEXT OF THE LORD’S PRAYER

Like I said, there are little differences between the words of the Peshitta text and the sung version of the Lord’s prayer in Aramaic: while the Peshitta has only “Forgive us our sins”, the sung text says, “Forgive us our sins and our debts (wahtohayn).” It’s pretty clear that this extra word has been added to the Peshitta text. But people have been singing it that way for quite a long time.

Here are overviews of the Curetonian and Sinaitic manuscripts of the Old Syriac texts. You can also see the first and second volumes of Burkitt’s Evangelion da-Mepharreshe (Cambridge University Press, 1904), containing the text of the Curetonian and Sinaitic manuscripts. Here is the Lord’s Prayer from Matthew 6 in the Curetonian text. To date, very little of the Vetus Syra is available online.

Want to know a bit more about how the very earliest Christian communities used and understood the Lord’s Prayer? If so, see my blog on the mysterious SATOR Square. The SATOR square is all about the Lord’s Prayer. And we can trace the square and its high Christology right back to the Roman church of the days of the apostles. You might also like Praying the Lord’s Prayer.