In the Bible, the Ineffable Name of God is spelled with the letters YHVH. But in biblical times, Hebrew had no written vowels. So how was the name actually spoken? Some folk think it was pronounced Yahweh (or Yahveh). But the evidence for this is so small that it doesn’t hold up at all. In fact, the evidence suggests they pronounced it Yehovah or Y’hovah, with the accent on the final syllable. Don’t believe me? Follow it with me here.

The Ineffable Name name of God—his personal and most sacred name—occurs 6,828 times in the Hebrew scriptures. It is written with the Hebrew letters yodh-heh-vav-heh – equivalent to the English letters YHVH. It looks like this. (Remember, Hebrew reads from right to left.)

יהוה

HVHY

Hebrew speakers call it the shem meforash or ‘explicit name’. In English, we usually called it the ‘ineffable name’ or, more often, the ‘Tetragrammaton’, a Greek word meaning ‘four letters’.

THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD IN ANTIQUITY

The Ineffable Name of God is very ancient. It appears in three Egyptian lists, from Soleb (late 15th century BC), Amarah-West (13th century BC), and Medinet Habu (12th century BC). The Soleb list, of which the later two seem to be copies, was written by the scribes of Pharaoh Amenhotep III. It speaks of six different groups of Shasu – Asiatic semi-nomads – known to the Egyptians as living in the Levant. One of these groups is the ‘Shasu of Yhw’.

The phrase has given rise to various opinions. Some think it refers to the early Israelites as the ‘Shasu of Yhw’. Others think it refers to the Edomites as early worshippers of this deity.[1] Still others think ‘Yhw’ is a place name, which took its name from the deity.[2] Yet, despite these different views, the consensus is that the name is an early mention of the sacred Name found in the Bible, though exactly what vowels accompanied the three consonants ‘Yhw’ is unclear.

The Bible and archaeological sources testify that the Israelites spoke the Ineffable Name of God freely in pre-exilic times. The Lachish ostraca, for instance, written during the Assyrian attack on Lachish in 701 BC, record a junior officer, Hoshayahu, using the Name as an oath, when writing to his captain Ya’ush.[3]

THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD NOT SPOKEN

But after the Exile, the speaking of the Name was increasingly circumscribed in order to protect it from profanation. In time, it was spoken only by the kohen ha-gadol on Yom Kippur. Then, the Talmud tells us, the priests ceased to speak the name at all.

Our rabbis taught: In the year in which Shimon HaTsadik died, he said to them that in that year he would die…. After the festival of Tabernacles, he fell ill for seven days, and then he died. His brothers the priests refused to pronounce the divine name when bestowing the priestly benediction. (Bavli Yoma 39b)[4]

There is a question about just who this kohen gadol Shimon HaTsadik was. Some think he is either Shimon I (c. 300–273 BC) or Shimon II (219–199 BC) and conclude that the Name ceased to be spoken in the third or early second century BC. Others say this Shimon is associated with the inauspicious signs that began forty years before the destruction of the temple (Y. Yoma 6.3), and that the passage above is directly followed by a description of these same signs. They therefore suggest Shimon HaTsadik lived in the first century AD. In that case, the kohen gadol Shimon may have been Shimon ben Kamithos (r. AD 17-18) or Shimon Kantheras (r. AD 41-43), which would mean the name ceased to be spoken in the first century AD. However, the majority still hold to the earlier date of third or second century BC.

THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD BANNED

Finally, following the Bar Kokhba Revolt of AD 132-135, the Romans banned the Name completely on pain of death, a ban which led to the martyrdom of R. Hanina ben Teradion.[5] Thereafter, the rabbis discouraged entirely the speaking of the Name, to protect the community. Not that this was done in any official way. The only Mishnaic authority in the matter is an addendum in the name of a minor second-century teacher, Abba Saul.[6]

All Israel will have a portion in the World to Come, as it is said, And all your people will be righteous; forever they will inherit the earth (Isa. 60.21). But these have no portion in the World to Come: One who says there is no resurrection of the dead; [one who says] there is no Torah from heaven; and an Epicurean. R. Akiva says: One who reads heterodox scrolls, and one who murmurs over a wound and says, All these diseases which I set upon the Egyptians, I will not set upon you (Exod. 15.26). And Abba Saul says: Whoever pronounces the Name literally.

Yet, in time, the ban became binding. The spoken vowels that originally accompanied the four consonants, YHVH, gradually became obfuscated, and knowledge of the true pronunciation was lost.

THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD AND THE MASORETES

However, when the Masoretic codices of the Bible appeared, from the ninth century on, it seemed that the Masoretes were in no doubt at all about the vowels of the Ineffable Name of God. The greatest of all these codices was Aharon ben Asher’s great codex of the whole Bible, later known as the Aleppo Codex (c. AD 920). At its first occurrence in the Aleppo Codex Psalms, at Psalm 1.2, we find the Name written with vowel points, as follows:

יְהֹוָה

Reading from right to left, the first consonant, yodh, has two dots below it, representing the sheva half-vowel. The second consonant, heh, has a dot to the upper left, representing the o-vowel ḥolam. The third consonant, vav, pronounced as a bilabial v, has the sign for the back a-vowel, qamats.[7] The closural fourth consonant, heh, although silent in later Hebrew, would have been pronounced in early biblical times as a short aspiration after the a-vowel.[8] Finally, since the cantillation mark in the Masoretic texts most frequently falls on the third consonant of the name, it suggests that the last syllable was the accented one.

These vowel points appear on the Ineffable Name of God throughout the Masoretic codices, although sometimes the middle vowel, the ḥolam dot, is omitted. Like this:

יְהוָה

Taken together, they make Ye-ho-vàh, which came into Latin as Iehova or Iehovah and so passed into the tongues of Europe as Jehovah. This remained the widely-accepted form of the Name until the nineteenth century.

DOUBT ON THE MASORETIC ‘YEHOVAH’

The first seed of doubt for the ‘Yehovah-Jehovah’ pronunciation was Elias Levita’s Masoret ha-Masoret (1538), which argued that the Masoretic punctillation was invented by the Masoretes themselves. This, as we saw in chapter nine, generated much opposition precisely because it threw into doubt the pronunciation of the sacred name. Yet Levita’s cue was followed by Génébrard, whose Chronologia (1567) proposed the pronunciation ‘Iahve’ on the strength of the testimony of the fifth-century Syrian Father, Theodoret.[9] Nevertheless, Jehovah was largely accepted for another two-and-a-half centuries until Wilhelm Gesenius’s influential Lexicon (1833), again on the testimony of Theodoret, proposed Jaheweh and Jahaweh, that is, with the German letters J and W being equivalent to English Y and V.

יַהֲוֶה יַהְוֶה

Following Gesenius, Ewald (1803–1875) proposed ‘Jahweh’, omitting the middle half-vowel. Through Ewald’s writings, the name came into widespread use. English writers, changing the German J to Y, but unaccountably hanging on to the German W instead of V, made it into Yahweh. This Yahweh-construct has now become the new orthodoxy, although it’s fair to add that numerous other conjectures are in circulation, including Yahaweh, Yahawah, Yahuwah, and so on.

DIFFICULTIES IN THE ‘YAHWEH’ CONSTRUCT

There are several difficulties with the ‘Yahweh’ or ‘Yahveh’ form of the Name. First, it is based on questionable testimony, that of the fifth-century Church Father, Theodoret, Bishop of Cyrus in Syria (c. 393–457). Theodoret wrote, The Samaritans call it IABE while the Jews AIA.’[10]

From this Greek form, IABE, Génébrard and Gesenius derived Yahaveh / Yahaweh. But Theodoret was no expert witness. He lived seven hundred years after the Name had ceased from common speech among the Jews. He did not know Hebrew, for his scriptural exegesis relies entirely on the Greek and Syriac translations. Further, whichever name Theodoret intended, he had the unenviable task of transcribing a Semitic name into the Greek alphabet, without any consonants corresponding to Hebrew heh or vav. It may even be that he was trying to write Yafeh, the Beautiful One, a Samaritan form of address for God.

DID SOMEONE CHANGE THE VOWELS OF THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD?

Second, Gesenius suggested that the vowels supplied by the Masoretes were not the true vowels of the Name at all. Instead, he said, the Masoretes substituted the vowels of Adonai, ‘my Lord’, beneath the four consonants, to show that Adonai should be read instead of pronouncing the true name. This, he said, was in line with the scribal practice called ketiv-kere – meaning ‘written-read’ – which occurs throughout the Masoretic codices. In ketiv-kere, the letters of a word written in the text are given the vowels of another word, whose consonants are written in the margin, to show that the marginal word should be read. In this case, Gesenius said, the sheva, ḥolam, and qamats vowels of the Tetragrammaton were not its real vowels at all, but borrowings from Adonai.

This might be convincing if the Masoretic vowels for the Tetragrammaton were indeed those of Adonai. But since they patently are not, the argument collapses. For while the Masoretic vowels for the Tetragrammaton are sheva, ḥolam, and qamats,the vowels of Adonai are ḥataf pataḥ, ḥolam, and qamats. If the Masoretes intended that Adonai should be read, why did they write sheva instead of ḥataf pataḥ ? Such an omission, required neither by grammar nor reverence, could only cause confusion. More, it undermines any notion of the Tetragrammaton’s vowels being a ketiv-kere, for every other Masoretic ketiv-kere substitutes the kere-vowels unchanged, even when the result is an impossible fit to the ketiv-consonants.[11] Further, every other ketiv-kere is noted in the codex margin, while no such thing ever appears with the Tetragrammaton.

WERE THE MASORETES RABBINIC JEWS?

Third, Gesenius’s assumption that the Masoretes would change the vowels at all is doubtful. In Gesenius’s time it was thought that the Masoretes were rabbinic Jews, who might well have attempted to conceal the Name. But we now know that the Masoretes were not Rabbanites at all, but Karaites, who rejected rabbinic tradition.[12] Unlike the Rabbanites, who did not speak the Name at all, the Karaite position was much more diverse. According to their 10th-century historian, Jacob Kirkisani, some thought the Name should be greatly restricted; others thought it might be used in prayer, reading, and liturgy; but yet others spoke it deliberately and often, rebuking those who replaced it with Adonai.[13] Yet all the Karaites were dedicated to preserving the Name.

As for the Masoretes, it appears, as we shall see, that their position was to discourage the speaking of the Ineffable Name of God in public Scripture reading. Yet they would have resisted any attempt to obscure its true pronunciation. They produced their great work of scholarship to preserve the true knowledge of the Scriptures for their own community. They had every reason not to conceal the true pronunciation of the Name.

HOW MANY SYLLABLES IN THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD?

Fourth, the true pronunciation of the Ineffable Name of God must possess three syllables. The second letter, heh, cannot be silent for, in pre-exilic Hebrew, there was no silent heh in the middle of words. It always carried a vowel or a half-vowel. In fact, the Leningrad Codex not infrequently places cantillation marks over the second heh, which shows that the second consonant was sung.[14] Since one cannot sing a silent letter or a half-vowel, the Name must have had had three vowels, of which the last two, which bear cantillation marks, were full and unreduced ḥolam and qamats – that is, o and a.

GESENIUS DIDN’T BELIEVE IT HIMSELF

Fifth, Gesenius himself was not nearly as convinced of the Yahaweh-Yaheweh form as is supposed. In his Lexicon, after noting Reland’s view, he makes a surprising volta-face:

Also those who consider that יְהֹוָה [Yehovah] was the actual pronunciation are not altogether without ground on which to defend their opinion. In this way can the abbreviated syllables יְהֹו [Yeho] and יוֹ [Yo], with which many proper names begin, be more satisfactorily explained.[15]

THE PLAUSIBILITY OF THE MASORETIC VOCALIZATION

Therefore, since even Gesenius thought his own proposals were not sufficient to dismiss the Masoretic vocalization, let us return to that vocalization – Yehovàh – and examine its plausibility.

Apart from the vocalized Tetragrammatons in the Masoretic text, hundreds of personal names in the Bible carry part of the sacred name. The Masoretes give these theophoric names a range of vowels – yo, yeho, yah, yahu – some of which seem to refute the Masoretes’ own vocalization of the Tetragrammaton as Yehovàh. This is surely testimony to the integrity of the Masoretic vocalization. For if they were trying to promote an alternative pronunciation, they would not have left the field so littered with contradictions. And if these variants can be reconciled on the basis of the ‘Yehovàh’ vocalization, it will confirm the correctness of that vocalization.

TWO FORMS OF THE NAME

According to the Masoretic vocalization, there were two forms of the Ineffable Name of God since ancient times: a form beginning Yeho and a form beginning Yah. Reading through the biblical timeline, the first form we meet is Yeho: in Genesis 2.4 the name of the Creator is vocalized as Yehovah. Two chapters later we meet the Yeho vocalization again: the antediluvians, we are told, began to call upon the name of Yehovah (Gen. 4.26). Indeed, the Yeho form – in Yehovah – is the only form of the name throughout Genesis.

Likewise, in Exodus, the Ineffable Name of God is consistently vocalized as Yehovah until, after crossing the Sea, we meet the first appearance of the Yah-form, which appears in the Song of the Sea: ‘Yah is my strength and song’ (Exod. 15.2). Throughout the other books of the Pentateuch, the only vocalization of the Name is Yehovah. Therefore, if the first five books of the Bible are purporting to report a historical narrative, as they surely are, then they are saying that Yehovah is the most ancient form of the sacred name, whereas Yah is not heard until the Exodus and, even then, is rare.

The first person to bear the Ineffable Name of God within their own name is Moses’ mother, Yo-kheved, ‘Glory of Yo’ (Exod. 6.20), where Yo is surely a contraction of Yeho, as it frequently is in the historical books (see below). The second person to bear the sacred name is Moses’ lieutenant, Hoshea ben Nun, who was surnamed Yeho-shua (Joshua) (Exod. 17.9; Num. 13.16; Josh. 1.1).

AFTER MOSES

Thereafter, no one else bears the Yeho form for many centuries until, in the Judges period, we find Yeho as a suffix in Mikha-yeho (Judg. 17.1) although, unlike Yeho-shua, this is not a declaration of the deity’s power, but a question, ‘Who is like Yeho?’ Not long after, we meet another Yeho-shua in the priestly town of Bet Shemesh (1 Sam. 6.14), after which names like Yeho-yada (2 Sam. 20.23) and Yehonadav (2 Sam. 13.3–5) become quite common.

Then, from the Judges period on, the Yo prefix also appears: Yoash (Judg. 6.11); Yotam (Judg. 9.5, 7); Yonatan (Judg. 18.30; 1 Sam. 13.16); Yoav (2 Sam. 2.13); Yonadab (2 Sam. 13.3). Then, last of all, from the time of Saul, the Yah suffix appears in Israelite names: Aḥi-Yah (1 Sam. 14.3); Tseru-Yah (2 Sam. 2.13); Bena-Yah (2 Sam. 20.23); Uri-Yah (2 Sam. 11.3); Adoni-Yah (1 Kgs 1.5).

WHICH FORM IS OLDER?

Therefore, following the Masoretic vocalization, the Yeho and Yah forms of the Name are both old, but Yeho is the more ancient by far. It was known, according to the Masoretes, in antediluvian times; its contracted form, Yo, appeared during the Egyptian captivity, while the first person to bear the full Yeho prefix was great Yehoshua in the Sinai wanderings.

The Yah form is first encountered at the Exodus, but is not found in Israelite names until the early monarchy period, in the late 11th century BC; it is invariably a suffix, never a prefix, and is first borne by people of no repute, such as Aḥi-Yah, son of the wicked kohen Pinḥas ben Eli (1 Sam. 14.3). Therefore, the order of appearance of these variants suggests that the older vocalization of the Name begins Yeho and that Yah is a later, derivative form.

THE THIRD SYLLABLE

For the third syllable of the Tetragrammaton, the Masoretes give two options: –vah and the much rarer –vih, which we shall discuss below.The -vah form appears the more authentic, not only by its frequency, but also by the large number of instances where poetic texts place the accented last syllable of the Tetragrammaton to rhyme with another a-syllable. Here are a few examples:[16]

Arise, Yehovàh Qumàh, Yehovàh

Return, Yehovàh Shuvàh, Yehovàh

How long, Yehovàh Ad-anàh, Yehovàh

The law of Yehovàh is perfect Torat Yehovàh temimàh

The statute of Yehovàh is pleasant Edut Yehovàh ne’emanàh

The command of Yehovàh is pure Mitsvat Yehovàh baràh

The fear of Yehovàh is clean Yir’at Yehovàh t’horàh

Your goodness, Yehovàh Tuvkhà, Yehovàh

Your name, Yehovàh Shimkhà, Yehovàh

Yehovàh, save us now Anàh, Yehovàh, hoshia-nà

Yehovàh, deliver us now Anàh, Yehovàh, hatsliḥah-nà

MORE ANCIENT EVIDENCE FOR YEHOVAH AS THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD

Finally, apart from the Masoretic text, there is other ancient evidence for the pronunciation Yehovàh. A Hebraic Greek magical papyrus from the 2nd or 3rd century states εληιε Ιεωα ρουβα, ‘My God Ieoa is mightier.’[17] Ιεωα, being about as close as the Greek alphabet can get to writing Yehovàh, supports the Masoretic pronunciation. Ten centuries later, the Name appears in Latin as ‘Iehova’ in Raimundo Martini’s Pugio fidei (1270). Whether Martini learned this pronunciation from his mentor,the Jew-Christian Pablo Cristiani, or whether, as some have suggested, Martini was himself of Jewish origin, is not clear. But he knew ‘Iehova’ at a time when it existed, so far as we know, only in a few Masoretic manuscripts far away from Barcelona. Perhaps the great community of Spanish Jews had preserved a spoken tradition of the Yehovah pronunciation.

All in all, then, there is evidence to confirm that the Masoretic vocalization, Yehovàh (hereafter Yehovah), is a likely ancient pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton. But can it provide an explanation for all the anomalies of the case? Where did the name Yah come from? And what about Yahu and Yehovih?

DOES ‘YEHOVAH’ EXPLAIN THE ANOMALIES?

YAH

After its first appearance in the Song of the Sea (Exod. 15.2), Yah appears in later poetic texts, especially the Psalms, with their ancient acclamation, ‘Halelu-Yah!’[18] In every such case, the second letter of the Name, heh,contains the dot mappiq, showing that the final h-consonant is to be pronounced as an audible breath or aspiration just after the vowel, as with the last letter of Yehovah.

יהּ

But proper names, from the time of Saul on, display Yah as a suffix without the mappiq-dotbreath. There is no reason to doubt that this is the same name. However, it is not clear whether the dot reflects a later pronunciation or simply a later orthography of the final heh.[19]

The likeliest explanation for the origin of Yah is that it is a contraction of Yehovah, preserving the first consonant and last accented vowel and aspirated heh, and omitting everything in between: Y-(ehov)-ah. Such contractions were always current among the Israelites: Ba‘al Meon became Beon (Num. 32.3, 38), Yehoshua (Num. 13.16) became Yeshua (Neh. 8.17), Yehoash is Yoash (2 Kgs. 12.1; 11.2); Ananias is Annas, and Epaphroditus is Epaphras. The same is true nowadays: Alexander is Alasdair, Augustine is Austin, Magdalena is Malena, Philippa is Pippa, Willem is Wim.

YO-

Yo is a contraction of Yeho. Evidence appears in the early monarchic period in names given both in the Yeho and Yo form: Yehonadav is Yonadav (2 Sam. 13.3–5); Yeho-ram is Yo-ram (2 Kgs 8.16; 9.15); Yeho-ash is Yo-ash (12.1, 19 [20]).

YAHU

From the ninth century BC, proper names appear with the suffix Yahu: Eli-Yahu (1 Kgs 17.1); Ḥizki-Yahu (Hezekiah), Yesha-Yahu (Isaiah), Yirme-Yahu (Jeremiah), Tsidqi-Yahu (Zedekiah).

יָהוּ

The likely origin of Yahu is that it arose naturally by expanding the final mappiq-dot breath of Yah to a carrier u-vowel, a paragogic vav. Although, in the Bible, Yahu is confined to theophoric suffixes on personal names, there is evidence that it was a spoken form of the Name among Judeans in late biblical times. In 407 BC, the Jewish kohanim in Egypt wrote the Name with the letters YHV, indicating Yahu or Yaho.[20] A Mishnah passage relates that they spoke a deliberate approximation to this name – Vahu – in the Hoshana Rabba festivities in late temple times (M. Suk. 4.5; B. Suk. 45a).

Around the beginning of the Babylonian-Exile period, proper names ending with the –yahu suffix begin to feature instead a –yah suffix, without any mappiq-dot. The Books of Chronicles feature both –yahu and –yah forms for the same name, Zechariah (2 Chr. 20.14; 24.20). Jeremiah uses both forms for the same man, Zephaniah the kohen, who is first Tsefan-Yahu and then Tsefan-Yah (Jer. 21.1; 25.5). In post-exilic times, the –yah suffix replaces the –yahu form.

YAHO

The Greek magical papyri have the form Ιαω, which represents Hebrew ‘Yaho’. In Hebrew o and u are the same in consonantal spelling and often differ little in pronunciation. Yaho is therefore Yahu.

YEHOVIH

In the Masoretic codices, when the Tetragrammaton follows Adonai, the first vowel changes from sheva to the short ‘e’, ḥataf seghol, and the last vowel receives the i-vowel ḥireq: Yehovìh.[21]

יֱהֹוִה

In such cases, the Masoretes appear to have replaced the first and last vowels of the Name with those of elohim in order to show that the reader should read Adonai Elohim rather than an awkward Adonai Adonai.

WHAT THE MASORETES WERE REALLY DOING

From this we can discern the true practice and intent of the Masoretes. Their practice in reading was to substitute Adonai for the Tetragrammaton. When the infrequent Adonai YHVH combination appeared, they showed, by substituting two vowels of elohim, what form should be spoken. Wherever else the Tetragrammaton appeared, they either preserved the original vowels complete, assuming that the reader would know to substitute Adonai, or else they gave only two vowels, sheva and qamats, omitting the ḥolam dot.[22]

יְהוָה

The frequent omission of ḥolam is unlikely to have been an error. Aharon ben Asher was not so careless as to err so often, nor to leave so many errors uncorrected. More likely is that the omission of the ḥolam o-vowel was another signal that the Name should not be pronounced. But otherwise, they did not change the Name. The purpose was to signal, not conceal.

THE MEANING OF THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD

The Bible tends to explain significant names. Many, like Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Moab, Ammon, Jacob, Judah, Benjamin, Moses, or Solomon, are explained where they occur; some, like Joseph, have two meanings; others, like Edom, require some deduction.[23] But the clarification is usually somewhere nearby. The Tetragrammaton receives its explanation at Exodus 3.14, where the Holy One calls himself eheyeh asher eheyeh, ‘I am what I am.’ Or as the Septuagint renders it, Εγοειμιοων, ‘I am the Existing One.’ From this we deduce that the Tetragrammaton, which follows in the next verse, is what it appears to be, a form of the verb hayah,‘to be’.

Some think ‘Yahveh’ or ‘Yahweh’ is a hifil or causative form of hayah, meaning ‘He who causes to be’, this despite the fact that a hifil of hayah is unknown in the Bible.[24] However, unknown hifil-forms aside, eheyeh asher eheyeh refers to immutable self-existence rather than creative power and explains perfectly the form Yehovah. The first consonants suggest the future (imperfect) form of the verb, yih; the middle syllable suggests the present participle hoveh; and the last syllable suggests the perfect tense, hayah. Taken together, it would mean ‘Who is and was and is to come’ or, as the synagogue sings each Shabbat, ‘And he was, and he is, and he will be in glory.’[25]

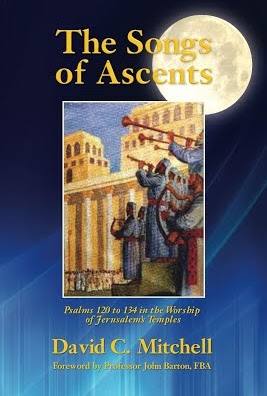

This blog is from Appendix 1 of my book, The Songs of Ascents: Psalms 120 to 134 in the Worship of Jerusalem’s Temples (2015).

ONE MORE PUZZLE

Their remains one last puzzle. How did they pronounce the Tetragrammaton after prefixes?

In normal practice, the prefixes v- (ו), l- (ל), b- (ב), and k- (כ) receive the vowel sheva.

le-david to David

When a prefix precedes a definite article or when the noun begins with an a-vowel, the prefix takes an a-vowel.

le-ha-melekh → la-melekh to the king

le–adonai → ladonai to my Lord

But when a noun begins with yodh and sheva, the two shevas and yodh coalesce to the i-vowel hireq.

le-yerushalayim → lirushalayim to Jerusalem

So what we would expect with prefixes before the name Yehovah, would be two shevas becoming hireq.

le-Yehovah → lihovàh to Yehovah

However, what we actually see everywhere is that the prefix receives the a-vowel, while the first letter of the Name has no vowel indicated at all.

la-yhovàh to Yehovah

TWO POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS

There are two possible explanations for this anomaly. The first is that the prefix + a-vowel signal the reader to read Adonai instead of the Tetragrammaton. For, as we saw, a prefix before Adonai simply joins the vowel:

le–adonai → ladonai to my Lord

The second possibility is that the la-prefix is a unique form of reverence for the Name. Saènz-Badillos notes such a usage, which resembles familiar vocative forms taking the definite article, like ha-melekh, ‘O King’ (Est. 7.3) or ha-elohim, ‘O God’ (Judg. 16.28).[26] In that case, the pronunciation would be either lahovàh – with no vowel on the yodh, as in the codices – or la-y’hovah, taking the missing sheva in the codices as defectively written.

While the second option sometimes appeals on poetic grounds – for instance, la-Y’hovàh ha-y’shu‘àh, ‘salvation belongs to Yehovah’ (Ps. 3.8) – it is probably better for now to avoid unknown forms and stay with known procedures of vowel-modification. I therefore read a-vowel prefixes before the Tetragrammaton as a Masoretic sign that it should be pronounced Adonai, and that the true pronunciation of the Name with prefixes follows the rules of two coalescing shevas, that is, lihovàh, vihovàh, bihovah, or kihovah.

THE INEFFABLE NAME OF GOD IN THIS BOOK

One would not want to say that there are now no more questions about the vocalization of the Tetragrammaton. Yet, on the basis of the evidence above, I suggest that Yehovah is more likely than Yahweh-Yahveh. It is certainly the vocalization which the Masoretes favoured, and I imagine Aharon ben Asher knew much more about the matter than Theodoret, Gesenius, or Ewald. And so, for these reasons, I have employed ‘Yehovah’ in transcribing the Masoretic cantillation of the psalms in this book.

NOTES

[1] Redford 1993: 272–73.

[2] Astour 1979: 20–29.

[3] Ahituv 1992: 36-41.

[4] B. Yoma 39b; Y. Yoma 5.2; cf. M. Sot. 7.6; Tam. 7.2; B. Sot. 38a; T. Sot 13.

[5] See the martyrdom of R. Hanina ben Teradion at B. AZ 17b–18a.

[6] M. Sanh. 10.1.

[7] Some maintain that Hebrew vav or waw (ו) was anciently pronounced as w, like Arabic waw. However, every known form of Hebrew since medieval times pronounced it as bilabial v. So too in the Bible, from 10th century BC Ephraim to the 6th century BC Judean exile, the Hebrew word for ‘back’ is written גו (gav) or גב (gab) interchangeably, showing that vav was equal to the bilabial v or soft bet (1 Kgs 14.9; Ezek. 23.35; cf. 10.12). The v sound is therefore to be preferred, the more so because the w is comical to speakers of modern Hebrew.

[8] This is evident from the way it modifies the opening bgdkft consonants of following words, as, for instance, at Ps. 127.3, where the daghesh on banim shows that the preceding sound is a consonantal heh and not simply an open a-vowel.

[9] Génébrard 1567: 79; cited by Parke-Taylor 1975: 79.

[10] Theodoret of Cyrus, Question 15 in Exodus 7.

[11] See, in both Leningradand Aleppo, 1 Sam. 5.9; 6.4, where the sheva of teḥorim, inserted in the consonants עפלים, produces the impossible ayin with vocal sheva; or Jer. 42.6 where the vowels of anaḥnu are added to אנו, giving the impossible combination of shuruk and sheva on a single vav.

[12] As discussed in Chapter 11.

[13] Gordon 2012: 103.

[14] I say ‘may’ because, in each case, the Aleppo Codex positions the cantillation mark further right, nearer the yodh: e.g., Exod. 3.15, 16 (gershayim); Pss. 80.19 [20] (tsinnor); 84:[8] 9 (tsinnor); 96.10 (tsinnor); 99.5, 9 (tsinnor); 104.1 (oleh ve-yored); 106.47 (tsinnor); 109.21 (tsinnor); 130.7 (oleh ve-yored); 142.6 (oleh ve-yored).

[15] Gesenius, Lexicon (tr. Tregelles), p. 337.

[16] Num. 10.35; Ps. 3: Ps. 132.8; Num. 10.36; Ps. 13.1; Ps. 19.8–10; Ps. 25: 7, 11; Ps. 118.25.

[17] British Museum Greek papyrus CXXI 1.528–540 (3rd cent.); cf. Alfrink 1948: 43–62.

[18] Exod. 15.2. Yah occurs forty times in the Psalms: once in Book II (68.5), twice in Book III, seven times in Book IV, and thirty times in Book V, including the Halelu-Yah acclamations.

[19] The mappiq-dot may indicate that the orthography of Yah is later than that of YHVH. For, in early Hebrew, when the final heh was routinely vocalized, then a mappiq-dot on YHVH was unnecessary. But when, in kingdom times, the final heh became silent, the mappiq-dot was introduced to preserve the aspiration on the final consonant. Its presence in Yah therefore suggests a later written form. Such consistent use and non-use of mappiq not only supports a temple-period origin for the punctillation but testifies to the exacting nature of the Masoretes’ work.

[20] The ‘Petition to Bagoas’, Pap. I of the Elephantine Papyri.

[21] See, e.g., Aleppo Codex Judg. 16.28; 1 Kgs 2.26; Pss. 69.6 [7]; 71.5, 16; Isa. 22.5; Jer. 4.10; Ezek. 24.3, 6, 9, 14, 21, 24; et passim. The Leningrad Codex features this form also in the Pentateuch (absent from Aleppo), e.g., Gen 15.22; Ezek. 24.3, 21, 24.

[22] See, for instance, throughout the first extant page of the Aleppo Codex (Deut. 28), and, in the Leningrad Codex, all occurences of the name up to Gen. 3.14.

[23] Gen. 5.29; 17.5; 18.12–14; cf. 21.3; 19.37–38; 25.26; 29.35; 35.18; Exod. 2.10; 1 Chr. 22.9; Gen. 30.23–24; 25.25.

[24] Albright 1924: 374; Freedman 1960: 152; Cross 1962): 251–53; Dahood 1965–70: I.64, 177; Parke-Taylor 1975: 59–63.

[25] Rev. 1.4; ‘Adon Olam’, attrib. to Yehudah ha-Levi: V-hu hayah, v-hu hoveh, v-hu yihyeh b’tifarah.

[26] “We have good evidence for לַי׳ (la-Y.) ‘truly, Y. is…’ (Ps 89:19) or as a vocative (Ps 68:34)” (Sáenz-Badillos 1993: 60).