THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS

THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS have provided the greatest source of new insights into biblical studies in the last hundred years. The story is well known now. A Bedouin shepherd boy discovered the first scrolls in 1946. Later, other scrolls were discovered, making a total of thousands of documents which originated from the Judean state in the years 200 BC to AD 70.

When they were first discovered, in many different caves, some scholars said that they had all issued from a community in Qumran on the Dead Sea. As a result, they numbered them after the “Qumran” cave where they found them. 4Q175, for instance, was document 175 from Cave 4.

Their discovery and coming to market coincided with the declaration of the State of Israel in 1949. This “birthday gift” to the new Israeli state had a far-reaching effect. It gave them a window into their beliefs when the Romans tore statehood from them 2,000 years ago. What they saw through this window was striking indeed. It was a form of Israelite belief utterly different from rabbinic literature and its preoccupation with observation of the oral law. Instead, the Dead Sea Scrolls witness to the belief that its writers were living in a pivotal age, that the Messiah was coming soon.

There is, for instance, the Melchizedek Scroll which anticipates a heavenly saviour called Melchizedek coming to earth. He is clearly identified with Yehovah the God of Israel. But he is also the Messiah. Even more, he is also the Melchizedek figure of Psalm 110 who receives the promise of eternal dominion and priesthood. It shows that the Israelites of 100 BC were eagerly anticipating a Messiah who would be a divine priest-king.

Then there is the War Scroll, which looks for a hero, the Prince of the Host, who will come and lead Israel in battle against the Romans. Of course, it is no secret that the Israelites wanted rid of the Romans. But what is striking is that once more this Prince of the Host is clearly a heavenly figure. In fact, he has no name, it looks like he is the same Melchizedek as in the Melchizedek Scroll.

Then there is the Testimonia Scroll (4Q175) which contains a series of four testimoniums pointing to four different Messiah figures which the writer was expecting would appear, as spoken of in Zechariah 1:20. These figures are (1) a Prophet like Moses; (2) a King Messiah, the Star from Jacob; (3) a Priest Messiah; and (4) a Joshua-Joseph Messiah.

Then there is the Joseph Apocryphon (4Q372) which dates from at least 200 BC. It recounts the sorrows and the death-throes of a Messiah figure called ‘Joseph’. He appears to be dying at the hands of his foes, yet he dies predicting his own resurrection. I have argued that this figure shows what some Israelites believed about the suffering Josephite Messiah well before Christian times.

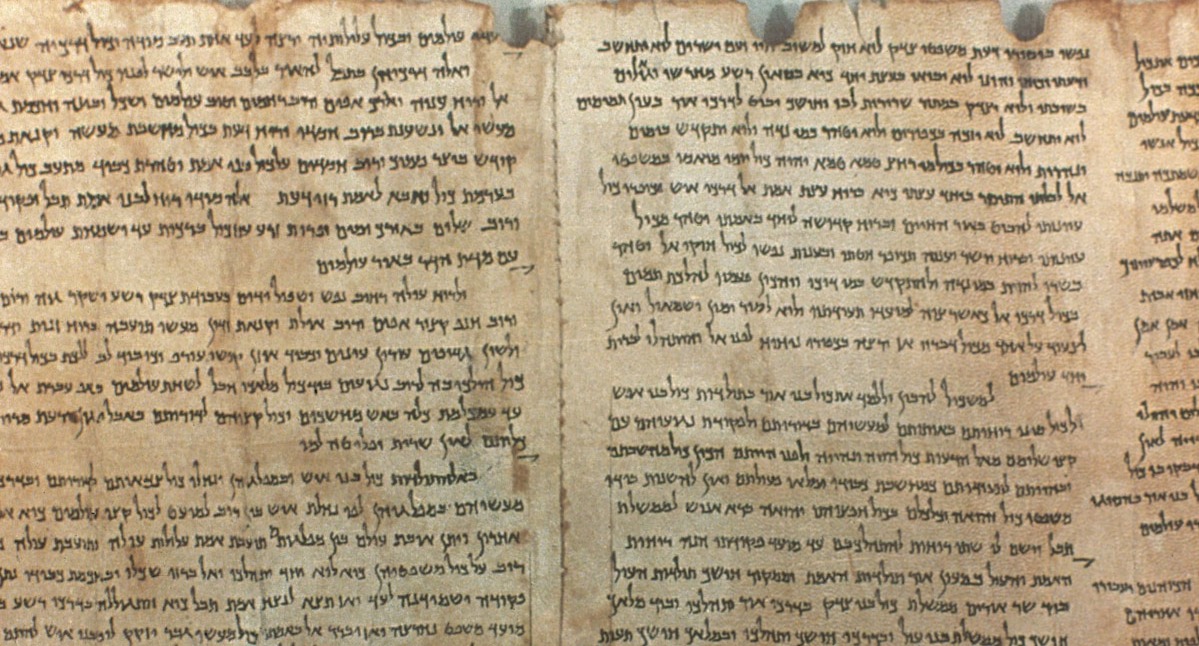

Finally, there is the value of the Dead Sea Scrolls as the earliest witnesses to the Bible text. The image at the top of the page is the Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa), discovered in 1946. It is a remarkable witness to Hebrew scribal fidelity. Its text is virtually identical to the 10th-century AD Aleppo Codex text which forms the basis for the best modern translations.

Well, that is just a brief of brief introductions to the Dead Sea Scrolls. But no modern study of the Bible can be complete without knowing about them.

I deal with the Dead Sea Scrolls throughout my work, but particularly in Chapter 1 of The Message of the Psalter, in Chapter 6 of Messiah ben Joseph, and in Chapter 4 of Jesus: The Incarnation of the Word.