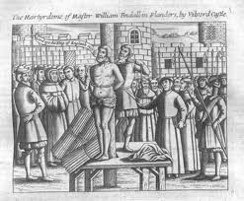

If you ever visit Brussels, and drive out past Zaventem Airport, then you will come to the pleasant Flemish town of Vilvoorde. The town maintains a Tyndale Museum. It also has a little patch of green called Tyndale Park. There football pitches jostle with a monument erected in honour of the English Reformer William Tyndale, who was martyred at the town’s south gate on 6 October 1536. This is the tale of Tyndale and his triumph in translating the Bible into English.

Tyndale was born in Gloucestershire around 1494. He was ordained and received his Master’s at Oxford. He then went to Cambridge where Erasmus had revived the study of Greek. Every serious student was reading Erasmus’s New Testament in the original Greek. And many, like Tyndale, were appalled at how the church of their day had corrupted the faith of the New Testament.

For the church of Tyndale’s time was corrupt indeed. Like the Sadducees of old, the priests of the Renaissance had turned the vineyard of the Lord of hosts into an enterprise for their own glory.

INDULGENCES

On the one hand, the popes extracted huge sums of money from the common people by selling “indulgences”. The clergy claimed these costly documents would redeem the souls of the dead from Purgatory. They were, in effect, selling tickets to Paradise.

Yet, on the other hand, they had framed laws throughout Europe, forbidding the people from reading the Bible in their own tongue. In England this law was called The Constitutions of Oxford. Dating from 1405, it prohibited the reading or translation of the Bible in English without a Bishop’s license.

Master Tyndale returned to Gloucestershire. But his great concern was the spiritual plight of the English poor. How could the church forbid the common people to read the gospel in their own tongue? And so, Tyndale began translating the New Testament. In between, he preached publicly in Bristol, quoting the gospel in English, proclaiming salvation by faith, castigating the Pope, and disputing with the church leaders of his day.

All this, of course, was truly dangerous. He was summoned to a church court. The risks were real, as he well knew. Only two years before, seven working people had been burned at the stake for teaching their children the Lord’s Prayer, the Commandments and the Creed in English. Yet, this time, Tyndale was released with a warning to keep out of trouble.

He pressed on with his translation. All that was needed to circumvent the law prohibiting Bible translation was a Bishop’s license. So Tyndale moved to London.

LONDON

When he arrived in the English capital, he presented himself to Bishop Tunstall, declaring himself willing and able to translate the scriptures into English. But the Bishop would have none of it. He turned Tyndale out. Tyndale concluded, “I perceived that not only in the Bishop of London’s palace, but in all England, there was no room for attempting a translation of the Scriptures.”

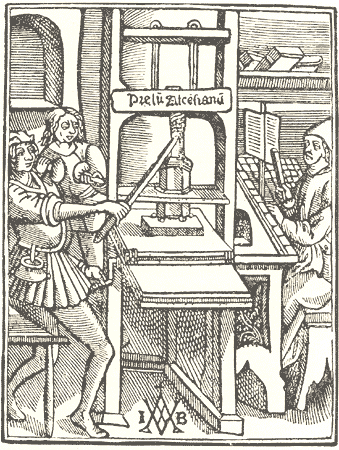

And so in 1524 Tyndale quietly left England. He sailed first to Hamburg, then Wittenberg, where he finished his New Testament translation and met Martin Luther and other German reformers. The following year, he left the safety of Wittenberg for Cologne, to be nearer the English trade routes. There he began printing his New Testament.

GERMANY

But word of the printing reached the Senator of Cologne, a friend of Henry VIII. The printed pages were seized and Tyndale fled the city. He arrived in Worms and began printing again there. And the following year the first consignment of 3,000 Tyndale New Testaments arrived at London Docks, hidden in bales of cloth. They were surprisingly cheap, around half the weekly wage of a labourer. And as soon as they appeared, they were eagerly bought up. The English gospel began to spread through the country. But Bishop Tunstall was outraged. He called Tyndale’s New Testament a “pestilent and pernicious poison which will infect the flock.” He bought up as many copies as he could for burning. In his rage, he even sent agents to the continental ports to buy up the Testaments in bulk for destruction.

But Tyndale continued to publish, refining his translation with each revision. The ships took the Testaments to other ports, as far north as St Andrews, and they spread through the land. In fact, much credit for the spread of Tyndale’s Testament must be given to the merchants and their ships. For the profit in the sale of them was far outweighed by the risk of seizure of cargo and imprisonment. Yet, many of the merchants, men like Monmouth and Poyntz, were men of evangelical heart and actively supported Tyndale and his work. Meanwhile Tyndale, having learned Hebrew, translated the Books of Moses and other parts of the Old Testament. Soon these too arrived in England.

TYNDALE’S LIFE

As one looks at Tyndale, one is struck by the stature and character of this English Reformer. His scholarship was second to none. Herman Buschius, the Wittenberg Professor of Rhetoric, said of Tyndale that, he “is so skilled in seven tongues, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, English, and French, that when he speaks them you might think it is his native tongue.”

As for his life, even his bitter opponent, Sir Thomas More, confessed that he was “a man of right good living, studious, and well learned in Scripture, who looked and preached holily.”

Some Reformers lived lives of relative ease. After Luther’s brave stand at the Diet of Worms, he lived safely and in great honour at Wittenberg. Having discovered the freedom of the evangelical gospel, he forsook his vows of celibacy. He wedded Catherina von Bora and rejoiced in the novelty of clean bed-sheets. Many other Reformers also took to the married life. But Tyndale was celibate all his days, focused on his task of translating the Bible.

Luther drank his Wittenberg beer in his glass inscribed with the Ten Commandments. He announced that he drink to “Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery” in one gulp! Calvin, for his part, said that Luther always allowed himself too much liberty. Yet Calvin, the Frenchman, declared that the Lord provides amply for our all our needs and we needn’t drink cheap plonk. But Tyndale lived as a hunted fugitive for thirteen years, enduring a hand-to-mouth existence most of the time.

Some Reformation leaders made grave errors of judgement. There was the bloody suppression of the Peasants’ Revolt in Luther’s Germany; the harsh legalism and the burning of heretics in Geneva; the civil war which erupted among the Swiss cantons; and the continual divisions over the nature of the Lord’s Supper. But Tyndale, years ahead of his time, appealed for unity on essentials.

Other Reformation leaders set up new ecclesiastical systems bearing their names. Tyndale had no such ambition. His reply to his critics was always the same: “Let but the King issue a Bible in the English tongue and I shall cease my labours forthwith.”

INCREASING OPPOSITION

Within the decade, Tyndale’s work was flooding England. But the powers that opposed reform were out to stop him. King Henry sent spies to find him. So did Henry’s men, first Thomas More, then Thomas Cromwell. There is a moving story of how Cromwell’s agent, Stephen Vaughan, was looking for Tyndale in Antwerp. They told him that a man wished to meet him outside the city, and he cautiously went out to meet him in the open fields. “Do you not know me?” the man said. “No,” replied Vaughan. “I am William Tyndale, whom you seek,” said Tyndale. Vaughan told him that the king offered him a safe pardon if he would return to England. Tyndale recounted his hardships in his exile – his hunger, thirst, homelessness, and cold, and his “bitter absence from my friends”.

He explained how he wanted to return to England, but he could not. For he feared that the King would revoke his pardon under pressure from the clergy, who would insist that promises made to heretics were not binding. (Perhaps Luther told him how this argument had been used at his trial in Worms.) “But”, said Tyndale, “let but the King license the Scriptures in the English tongue and I shall cease my labours and return to England forthwith.” Vaughan was so impressed by Tyndale that he warmly commended him to Cromwell and was sharply rebuked in return.

The bitterest of Tyndale’s opponents was the new Bishop of London, John Stokesely. Stokesley’s men eventually traced Tyndale to Antwerp, where Tyndale was at last living in a degree of comfort among the English Merchant community.

HENRY PHILLIPS

And there, in 1535, appeared Henry Phillips. This decadent young aristocrat traced Tyndale to the English Merchant’s House, where Tyndale was finally living in a degree of comfort for the first time since his exile began. Presenting himself as a supporter of reform, he gained the trust of the merchants and of Tyndale himself. On May 21st, he appeared at Tyndale’s door and made an appointment for dinner that evening. When he reappeared in the evening, he casually asked for a loan of two pounds – a sum equivalent to about two thousand pounds today – which the good-hearted Tyndale gave him. Then Phillips, pocketing the money, led Tyndale outside and delivered him to a gang of concealed men who bound and abducted him.

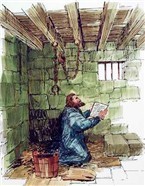

The time was right for Phillips. Henry’s divorce of Catherine of Aragon meant there was no English Ambassador in the Spanish Netherlands. As a result, Tyndale fell into the hands of the civil authority here in Brussels, who imprisoned him in Vilvoorde Castle, the state prison for the Low Countries.

In its dungeons, Tyndale lay for eighteen months, while the authorities appropriated his goods at a charge of five shillings a day for his food and guard. He passed the winter, shivering and ill. In summer 1536, he was tried for heresy. The charges against him were brought by three fine doctors of theology from Louvain. All were handsomely paid for their services; all found him guilty. In August, he was defrocked and excommunicated.

TYNDALE’S DEATH

Two months later, on October 6, he was led from the Castle to the town gate. They gave him an opportunity to recant, but remained silent. His last words, heard by the crowd, were “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes!”

Then he was bound to a stake, strangled and burned. And so William Tyndale passed from death to life.

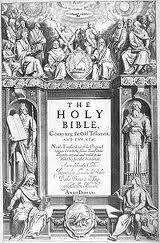

Tyndale’s last prayer was answered before the year-end. The King was presented with Coverdale’s Bible, which contained Tyndale’s New Testament and Pentateuch virtually unaltered. He commanded, “In God’s name, let it go forth among the people.”

Two years later, he ordered every church in England to display one Bible in English. When the King James Bible was published in 1611, its New Testament and Pentateuch were 90 percent Tyndale.

Preserved within the King James Bible, Tyndale’s translation transformed the English-speaking peoples. It made Britain a land of literacy and literature. It gave birth to the Puritan revival in the 17th century, to the evangelical awakening in the 18th, and the evangelisation of the world in the 19th and 20th centuries. In fact, it is thanks to Tyndale that you have an English Bible in front of you today. And, if you come from outside Europe, it is thanks to Tyndale that missionaries, with the King James Bible, came to your country with the gospel in your own tongue. It is ultimately thanks to Tyndale that we can go to the Biblegateway website and find the Bible in every major world language.

TYNDALE AND THE TRIUMPH OF THE BIBLE

How can we honour Tyndale: his love for the poor, his perseverance and endurance, his courage, his blood poured out for the gospel? Surely all he would ask us is that we read the Scriptures which he bought so dearly. He would tell us to read them early and late, to lay them to heart and study them. And if we reply that our age is not like his, when people laid down their lives for the word of God; that in our luxurious age, the word is available to all, but people despise it; he would reply that the oracles of God remain the most precious thing on earth.

Nothing here below will bring us greater good and blessing than regular Bible reading. It will be our shield when we rise and lie down. It will protect our coming and going forever. We should teach the Bible to our children. We should share it with our neighbours. Then we may bear thirty, sixty or a hundred times what was sown. And so we shall honour not only William Tyndale, but Tyndale’s master, who came from on high to translate God into human flesh.

Are you an admirer of Tyndale? Have you got a choir to hand? If so, you might like to try my Tyndale Communion Service. It’s an SATB communion service in quasi-16th-century style. It’s a free download.