The Bible tells us that the name of Jesus is the name that is above every name (Phil. 2:9–10). Is this just enthusiastic rhetoric? Or is this there really something special in this name?

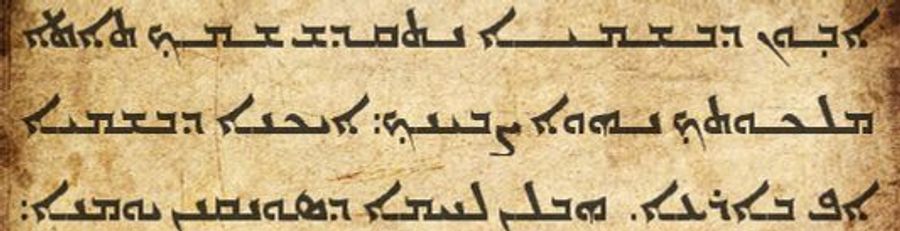

Before Jesus was born, Mariam, who would bear him, and Joseph, who would name him, each received instruction from on high that his name would be Yeshua (Matt. 1:21; Luke 1:31). In the Hebrew language, in which Matthew wrote his gospel, this involves a play upon words: You are to give him the name Jesus (yeshua‘), for he will save (yoshi‘a) his people from their sins (Matt. 1:21).

This same word-play conceals a statement about his divine nature. Yeshua is a later form of the name Joshua, which means ‘Yehovah saves’. But now it is this child who will save his people from their sins. And so, if it is Yehovah who saves, then this heavenly child is he.

Later, Paul says that this name, Yeshua, is the name that is above every name so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow (Phil. 2:9–10). And the writer to the Hebrews says that Jesus is as much greater than the angels as the name he has inherited is greater than theirs (Heb. 1:4). Is all this simply rhetoric, or is there something intrinsically powerful to the name of Jesus? Let’s start at the beginning.

YEHOSHUA TO YESHUA TO IESOUS TO JESUS

The name Yehoshua (in English, Joshua) is first given to the great Ephraimite commander Yehoshua ben Nun, who led Israel out of the desert and into possession of the Promised Land. Joshua’s name was originally Hoshea (Ho-shey-a‘), which means ‘salvation’ or ‘deliverance’.

הושע Hoshēa‘

The apostrophe at the end of the name signifies a characteristically semitic sound—the consonant ayin, which is a voiced pharyngeal fricative. (It can be heard in the gh of the word Afghan, when spoken by a native of that country.) For those unfamiliar with middle-eastern languages, it can be tricky, especially in the middle of a word. But, in this position, at the end of a word, it just means that the final vowel sinks into a soft throaty guttural.

Moses changed Hoshea’s name by adding one Hebrew letter y (yodh). In this way, the beginning of Hoshea became Yeho, a short form of the name Yehovah. A vowel was altered too—ē to u—changing the meaning from a noun, ‘salvation’, to a verb, ‘he saves’. (Neither of these vowels—ē or u—was written, for classical Hebrew does not require all vowels to be written.) And so Hoshea became Joshua, that is, Yeho-shua‘, meaning ‘Yehovah saves’ (Num. 13:16).[1]

יהושע Yehoshua‘

This prefix is significant. Joshua-Yehoshua becomes the first person in the Bible to bear the holy name Yehovah within his own name. Yes, Moses’s own mother, Yo-khebed, mentioned in Exodus 6:20, bore a very short form of the holy name. But she doesn’t actually receive the letters of the name in order, but just an abbreviation—Yo. But Joshua gets the first three letters of the Name, exactly as they occur in order, reading, of course, from right to left.

יהוה Yehovah

יהושע Yehoshua‘

In other words, Joshua-Yehoshua receives in his name a dose of divine power unlike anyone ever before him.

Now the name Yehovah is a portmanteau of the future, present, and past forms of the Hebrew verb ‘to exist’—yihyéh–hóveh-hayáh. It means ‘Will-be-am-was’. It is a declaration of eternal uncaused being. But the name Yehoshua goes further still. It declares that the eternally living self-sufficient one is present in the bearer of the name as the all-sufficient saviour. For anyone in need, it is truly a name above all names.

FROM YEHOSHUA TO YESHUA

Later on, other Israelites, like Joshua of Beth Shemesh (1 Sam. 6:14), bore the same name. But, a millennium after Joshua’s time, under the influence of Aramaic, the name underwent a change. The h softened and the two vowels of Yeho elided into a long e-vowel (ē, as in ‘hey’). The written form followed suit: the letter h (heh) disappeared and the o-vowel (from Yeho) moved up to become the u-vowel. (The Hebrew letter vav can represent either o or u.) Thus Yehoshua became Yēshua.

ישוע Yēshua‘

It then became quite a common name. Nehemiah lists several Israelite patriarchs called Yeshua among the returnees from Babylon (7:7, 11, 39, 43). Then he refers to historical Joshua ben Nun as Yeshua (8:17). Then both he and Ezra use the same name for their contemporary, the kohen gadol Joshua-Yeshua ben Jehozadak (Neh. 12:1, 7, 10, 26; Ezra 5:2; 10:18). Meanwhile Haggai and Zechariah still call the same man Yehoshua (Zech. 3:6–10; 6:9–14).[2] So at this time both forms of the name—Yeshua and Yehoshua—were interchangeable.

In the third century BC, the Septuagint translators of the Bible rendered ‘Yeshua’ in Greek. Their Greek transcription kept the long e-vowel of Yēshua. But, since the Greek alphabet had no letter sh,the sh became s. Then the final guttural ayin—another sound unknown in Greek—was removed along with its a-vowel. Then the name received the s-ending which terminates every Greek masculine name.

Thus Hebrew-Aramaic Yēshua‘ became Greek Yēsous or Iēsous (Ιησους). This form of the name became the standard written form of the name among Greek-speaking Israelites, like Ben Sira (and his grandson), Philo, Josephus, and the New Testament writers.[3] In time, the Greek form was Latinized as IESUS.[4] This then passed into English as Jesus.

Meanwhile, in Hebrew and Aramaic, Yeshua became commoner than Yehoshua. Joshua ben Nun is called Yeshua in the Dead Sea text, 4QTestimonium, which dates from about 100 BC. By Roman times, the short form of the name, Yeshua, had largely displaced the longer form, Yehoshua, in funerary inscriptions. Yet this short form, Yeshua, still carried the same meaning as its original: ‘Yehovah saves’.

THE NAME OF JESUS FOREKNOWN

Some Israelites expected the name of the Messiah to be Yehoshua or Yeshua. We first saw this in chapter two, in the promise to Joseph of a Messiah who would be a second Joshua. Later texts echo the same idea. The Dead Sea text, 4Q175, alludes to four messianic deliverers: a prophet like Moses, a star come out of Jacob (David), a priest Messiah; and a Joshua figure.[5]

We see it also in prophetic literature of the second and third centuries BC. Such texts often refer to the Messiah as ‘the deliverance-salvation of the Lord’. In Hebrew, the word for salvation, y’shu‘ah, even sounds like the name Yeshua. And the phrase, y’shuat Yhvh—in Greek texts, sotería kuríou—means‘the salvation of the Lord’. It is another way of saying Yeho-shua, ‘Yehovah saves’. Philo says as much: ‘Moses changes the name of Hoshea to Joshua…which means salvation of the Lord’ (sotería kuríou).[6]

So when second or first century BC Greek texts speak of ‘the salvation of the Lord’ (sotería kuríou), they are implying that the Messiah’s name will be Yehoshua.

- The book of Ben Sira, dating from the second century BC, says: ‘Happy are those who will live in those days and who will be permitted to see the salvation of the Lord’ (48:11).[7]

- The Testament of Dan is clear that this refers to a person: ‘There shall arise unto you from the tribe of Judah and of Levi the salvation of the Lord. He shall contend against Beliar and subdue him, and turn the hearts of the disobedient to the Lord, and give eternal peace to all who call upon him’ (5:10).

- And the Psalms of Solomon, from the middle of the first century BC, say, ‘The salvation of the Lord be over Israel his servant for ever’ (12:6). These texts are saying that the Messiah’s name will be Yehoshua/Yeshua.

This continues into the New Testament. John Baptist’s father, Zechariah, before he ever heard of Mariam’s baby, foretold that his son would ‘go before the Lord…to give his people the knowledge of salvation (y’shu‘ah)’ (Luke 1:77). Old Simeon, taking the baby Jesus in his arms, says, ‘my eyes have seen your salvation (y’shu‘ah)’ (Luke 2:30). Even Jesus seems to have played on the similarity of sound. When he enters Zacchaeus’s house, he says, ‘Today y’shu‘ah has come to this house, for this man too is a son of Abraham’ (Luke 19:9).

This belief that the Messiah was to be called Yeshua is seen in the prevalence of the name in early first-century Judea. In 2002, an ossuary came to light bearing the Aramaic inscription ‘Ya‘aqov bar Yoseph, the brother of Yeshua’. Many eminent authorities said it was from the first century, and that it was likely to be the ossuary of James (Jacob) the Just, the brother of Jesus. They pointed out that a brother’s name would not appear on an ossuary unless the brother were a person of exceptional significance, and that the occurrence of these three names was unlikely to be coincidental.

But others said it was fake, insisting, rightly enough, that the names Jacob, Joseph and Jesus—along with Judah—were by far the commonest male names in Jerusalem and Judea at the time. After ten years of court hearings the artefact was judged to be from the first century.[8] But the point remains about the popularity of these names. For it is actually very suprising.

One can understand why the name Jacob would be popular. He was the father of all the Israelites. But the popularity of Joseph and Jesus is much less easy to understand. For Joseph was the father of the Ephraimites and Manassites, and Joshua was an Ephraimite general. After the break-up of Solomon’s kingdom in 930 BC, the Ephraimites were Judah’s bitter enemies. And even after the Ephraimite kingdom was carried into exile in 722 BC, the Judeans remained at unceasing enmity with the remnant of Joseph, the Samaritans.

So one can see why first-century Judeans might call their sons Abraham, Moses, Aaron, David or Solomon. Yet these names, popular enough among medieval Jews, are absent from the populace of Jesus’s day. Instead, they loved the names Joseph and Joshua, the fathers of the hated Samaritans.[9] And this was not only among the ordinary people, but particularly among the rulers. In the century before Jesus was born, we find no less than seven high-priests bearing the name Yeshua. This suggests that the Israelites believed that the coming Messiah was to be called Yeshua, and they named their sons in this hope.

YESHUA TO YESHU

When we turn to rabbinic writing, we find that Jesus is mostly called Yeshu rather than Yeshua. In other words, the a-vowel and the letter ayin have been cut off the end of the name. At the same time, the stress moves from the second syllable to the first.

ישוע Yēshua‘

ישו Yēshu

This probably happened early. It appears in the Toldot Yeshu and in the tannaitic account of Jesus’s execution in Sanhedrin 43a: ‘On Shabbat on the eve of the Passover Yeshu was hanged’ (Sanh. 43a).

Since then, Yeshu has been the preferred form in Jewish usage. It’s fair to say it has often been used polemically. The Toldot Yeshu (see chapter ten) makes this quite clear. It tells how Miriam gave birth to a son and named him Yehoshua after her brother, but when it was found he was a mamzer the rabbis changed his name to Yeshu.Yet, throughout the whole period, there was a continual awareness that the real name was Yeshua. Among the manuscripts of Sanhedrin 43a, the Temani manuscript preserves Yeshua.[10] Likewise, the Vienna manuscript retains the name of Yeshua ben Pantera in the story of Rabbi Eliezer and Yaaqov of K’far Sekhanya (cited in chapter ten).[11] Later still, Maimonides refers to ‘Yeshua’, both in the passage from Mishneh Torah (cited in chapter ten) and in his letter to Yemen, but later editors changed it to ‘Yeshu’.

So we may ask, ‘How did this short form, Yeshu, arise?’ And ‘Why did the rabbis prefer it?’ And ‘Why does it remain to this day?’

This is an expanded version of Chapter 13 of my book, Jesus: The Incarnation of the Word (2021).

HOW DID ‘YESHU’ ARISE?

There are several views on how ‘Yeshu’ arose. Some say it was another contraction. As Yehoshua became Yeshua, so Yeshua became Yeshu. This is sometimes linked to Galilean dialect. For instance, the tanna Rabbi Yose the Galilean was presumably called Yosef, but his name is always given without the final letter. So perhaps Galileans did not pronounce the guttural ayin, and the end of the name was swallowed.[12] Flusser said,

The Hebrew name for Jesus, Yeshu, is evidence for the Galilean pronunciation of the period, and is in no way abusive. Jesus was a Galilean, and therefore the a at the end of his name, Yeshua, was not pronounced. His full name was thus Yeshua. In the Talmudic sources, which are from a later period, there is reference to a Rabbi Yeshu, who is not to be confused with Jesus.[13]

The a’ at the end of Yeshua is a guttural. And apparently some Galileans did mispronounce the gutturals. The Judeans found it hilarious.

A Galilean cried, ‘Who wants amar? [a bargain]’ They replied, ‘Do you mean ḥamor [donkey] to ride on or ḥamar [wine] to drink or amar [wool] to wear or imar [lamb] for slaughtering. (B. Erub. 53b)

Yet, Kutscher, the authority on Galilean Aramaic, says most Galileans, if not all, were perfectly able to pronounce gutturals.[14]

Nor should Flusser’s reference to another Rabbi Yeshu be simply accepted. Yeshu simply is not a Hebrew name. It does not correspond to any known Hebrew root and no other individuals are known ever to have borne this name. There are other people called Yeshua and Yehoshua in the Talmud, but every occurrence of Yeshu should be taken as referring to Jesus, despite some issues with dates.

Another view is that ‘Yeshu’ was a deliberate mutilation of the name ‘Yeshua’. This was the view of Lauterbach:

The name Yeshu by which Jesus is here mentioned is probably merely a shortened form of the name Yeshua. But since such an abbreviated form of the name is not used in any other case of a person named Yeshua or Yehoshua, but persistently and consistently used when the name refers to Jesus, it may be assumed that this shortening of the name was probably an intentional mutilation by cutting off part of it. The rabbis mention other instances of the names of persons being shortened because of their misconduct.[15]

This, I think, is a fair assessment, given later Jewish use of the name.

But perhaps the best explanation combines Galilean accent and mockery. Galileans did indeed omit the last syllable of the name. But the Judean hierarchy, keen to ridicule Jesus and diminish his influence, quickly turned this into what Kjær-Hansen calls ‘a vocal sneer’, mocking the Galilean accent, which they saw as ignorant and uncultured. This had the advantage of mocking both Jesus and his Galilean followers, and of distancing the speaker from both. Maybe ‘Yeshu’ was a Galilean nickname for ‘Yeshua’, just as Jim is short for James. And by picking up the nickname this way, the Judeans signalled that Jesus was a person of no consequence, fit to be spoken of in familiar and unceremonious terms.

So I think Flusser is mistaken in saying that the name Yeshu ‘is in no way abusive’. Among the Judean authorities it was always meant to be demeaning, as the Sefer Toldot Yeshu spells out. But perhaps it arose naturally from the Galilean speech of the disciples. Who knows, perhaps his mother called him Yeshu.

WHY IS YESHU STILL PREFERRED?

So the rabbis were always aware that the real name of Jesus was Yeshua, but they preferred the form Yeshu. In time, this name came to embody Jewish contempt for Jesus. Eisenmenger’s Entdecktes Judenthum (Judaism Uncovered) is polemical. But it was based on his dealings with Jews of his own time. His summary of why Jews use ‘Yeshu’ rather than ‘Yeshua’ looks like a fair summary of the facts.

- First, Jews do not recognize that Jesus is Messiah. Therefore they do not say ‘Yeshua’ (an honourable Hebrew name) but ‘Yeshu’.

- Second, Jesus was cut off, therefore the end is cut off his name.

- Third, Jesus was not able to save himself. That is wht the ayin is left out his name, removing any reference to the verb yasha‘,‘save’.

- Fourth, Jews are told to Make no mention of the name of other gods (Exod. 23:13). The Christians made him a god, therefore Jews cannot speak his name. In fact, Jews are not only permitted to mock false gods; they are commanded to change and defame their names.

- Fifth, the three letters of Yeshu are made into an acronym for a three-word curse that his name and memory be blotted out. When this is meant, the name is often written with the Hebrew sign for an acronym, the double apostrophe gershayim, inserted before the last letter: יש״ו.

To this day, Yeshu remains the standard form of the name of Jesus in modern Israeli school textbooks. In these texts it is written without gershayim, and so presumably no curse is intended. Nonetheless, the curtailed form of the name is standard throughout modern Israel.

Kjær-Hansen contrasts the work of Eliezer ben Yehuda, the reviver of modern Hebrew, with that of later prominent Israeli writers on Jesus. Ben Yehuda routinely referred to Jesus as Yeshua, signifying perhaps the need for a Jewish reappraisal of Jesus. But Joseph Klausner, the foremost 20th-century Jewish writer on the New Testament, invariably called him Yeshu. David Flusser also preferred Yeshu. Perhaps if Klausner and Flusser had followed Ben Yehuda, then the accepted term in modern Israeli discussion would now be Yeshua, not Yeshu.

AS HIS NAME IS, SO IS HE

But there is more to the name of Jesus. To find it, we must touch on numerology. Now, some find numerology subjective, lacking in rigour. But it has always been part and parcel of Israelite interpretation. It was also much studied by Renaissance humanists, like the great Johannes Reuchlin. So it has its place.

Before the invention of numerals, numbers were represented by letters of the alphabet. In Latin, of course, I was one, V was five, X was ten, L was fifty, and so on. But the same thing existed in Hebrew and Greek. And they made much of it. They had a whole science of deriving meanings from the numerical values of letters. In Hebrew it is called gematria and in Greek isopsephy.

The numerical values of the Greek alphabet are as follows:[16]

| Α | alpha | 1 | Ι | iota | 10 | Ρ | rho | 100 | ||

| Β | beta | 2 | Κ | kappa | 20 | Σ | sigma | 200 | ||

| Γ | gamma | 3 | Λ | lambda | 30 | Τ | tau | 300 | ||

| Δ | delta | 4 | Μ | mu | 40 | Υ | upsilon | 400 | ||

| Ε | epsilon | 5 | Ν | nu | 50 | Φ | phi | 500 | ||

| Ϝ | digamma | 6 | Ξ | xi | 60 | Χ | chi | 600 | ||

| Ζ | zeta | 7 | Ο | omicron | 70 | Ψ | psi | 700 | ||

| Η | eta | 8 | Π | pi | 80 | Ω | omega | 800 | ||

| Θ | theta | 9 | Ϙ | qoppa | 90 | Ϡ | sampi | 900 |

And the numerical values of the Hebrew aleph-bet are as follows:

| א | aleph | 1 | ט | teth | 9 | פ | peh | 80 | ||

| ב | bet | 2 | י | yodh | 10 | צ | tsade | 90 | ||

| ג | gimel | 3 | כ | kaf | 20 | ק | qof | 100 | ||

| ד | daleth | 4 | ל | lamedh | 30 | ר | resh | 200 | ||

| ה | heh | 5 | מ | mem | 40 | ש | sin, šin | 300 | ||

| ו | vav | 6 | נ | nun | 50 | ת | tav | 400 | ||

| ז | zayin | 7 | ס | samekh | 60 | |||||

| ח | ḥeth | 8 | ע | ayin | 70 |

Interpretation based on the numerical values of letters and names is basic to Hebrew interpretation of the Bible.[17] The best known example of Judeo-Greek isopsephy is in the book of Revelation: Let him that has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of man. And his number is six hundred and sixty six (Rev. 13:18).

The reason why 666 is man’s number, is because it falls thrice short of seven. In the world of the ancient east, seven is the number of completion or perfection. On the seventh day, God ceased from his work of creation and so the days of the week are completed by the seventh-day Shabbat.There are seven heavens. In the heavens are seven fixed spheres. Music, the language of heaven, has seven notes. The Book of Revelation, abounding in heavenly visions, also abounds in sevens. It has 54 explicit sevens, all signifying completion. Seven spirits of God signify divine omnipresence. Seven seals, seven trumpets, seven bowls, signify complete judgement. The beast’s seven horns and seven crowns represent his complete rule for a time. There are also many hidden sevens.

Seven, then, is the number of perfection, especially in Revelation. So it follows that, in Revelation, six is the number that falls short of perfection. And so the one called 666 is a trismegistus of imperfection. The number surely signifies Nero Caesar, whose name and title in Hebrew—נרון קסר—equal 666.[18] Yet Revelation presents the beast as being a figure yet to arise in the future. So it is best to see the beast as another Nero-like figure yet to come.

But, of course, if seven represents perfection, then eight represents that which is beyond perfection. As the eighth day begins a new week, as the eighth note begins a new octave, so the number eight represents a new dimension. And what John does not say, but certainly implies, is that, just as the beast’s number is 666, so number of the name of Jesus is 888.

| English | J | E | S | O | U | S | |

| Greek | Ι | Η | Σ | Ο | Υ | Σ | |

| Number | 10 | 8 | 200 | 70 | 400 | 200 | = 888 |

John didn’t need to spell it out, for the Greeks were well aware of the numerology of names. A graffito found on the wall of Pompeii says, ‘I love her whose number is 545.’[19] So John’s readers in Asia Minor would have understood well enough what he meant. Just as the beast is imperfect, Jesus is plus quam perfectum. Just as Jesus rose on the day after Shabbat, the eighth day, so he represents and initiates a new order of being altogether. All this is implicit in his name—888—thrice pluperfect.

But the name of Jesus yields hidden meaning also by Hebrew gematria. Indeed, both forms of the name, Yeshua and Yeshu, yield their own corresponding meaning. Let’s begin with Yeshua. Its value by gematria is as follows:

| English (right to left) | ‘ | u | š | y | |

| Hebrew | ע | ו | ש | י | |

| Value | 70 | 6 | 300 | 10 | = 386 |

Now one can juggle with gematria to obtain desired ends. But the honest way is simply to take the numerical value of a word and then transform that number straight back into another word in strict numerical value. And so, remembering that Hebrew reads from right to left, we get:

שפו = 386

Now this word, pronounced sh’fo, makes good sense in Hebrew. It comes from the old semitic root, shafah, ‘be visible’ and it means ‘eminent’ or ‘excellent’.[20] It’s a name which first appears among the sons of Esau in Genesis 36:23 and 1 Chronicles 1:40, when Edomites and Israelites still spoke the tongue they learned from their one father. But versions of the same name appear also among the Hebrews as shafan, yishpah, and yishpan.[21] Of course, ‘eminent’ or ‘excellent’ agree with the name of Yeshua, of whom it is said, He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the pre-eminence (1 Col. 1:18), and All the world has gone after him (John 12:19).

But what of that other name of Jesus, the name of ‘Yeshu’ by which the Pharisees mocked him and put him down? Its numerical value is as follows:

| English (right to left) | u | š | y | ||

| Hebrew | ו | ש | י | ||

| Value | 6 | 300 | 10 | = 316 |

Translated directly into Hebrew letters that makes:

שיו = 316

That spells the word sēyo, which in Hebrew means ‘his lamb’. It occurs in Deuteronomy 22:1: You shall not see your brother’s ox or his lamb going astray and ignore them. So, by gematria, the name ‘Yeshu’ tells us that Yeshu was ‘his lamb’, that is the Lamb of God, astray from heaven into earth. There he should have been received with tenderness, but instead he was despised and mocked, his name turned to a curse. Thus he became the Lamb of God, foretold by Isaiah, who takes away the sins of the world.

THE NAME OF JESUS: NOMEN EST OMEN

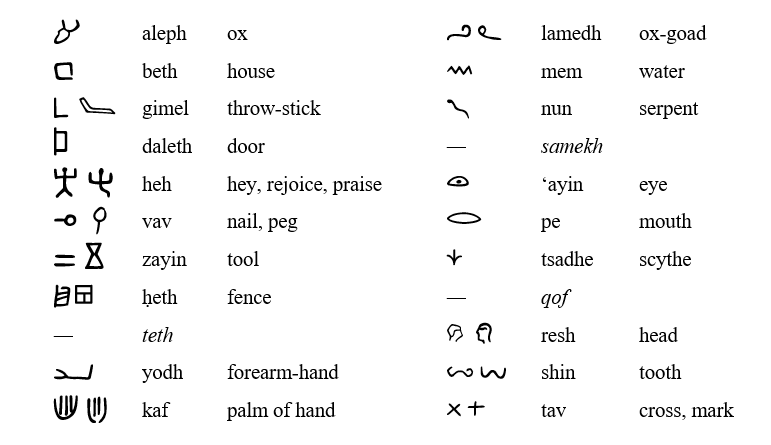

But there is more. Every letter of the Hebrew aleph-bet is also a picture. And from these pictures, hidden meanings can also be read. To understand this, we must go back to the beginnings of writing.

The earliest Egyptian pictographs, simple mnemonical glyphs, appeared in pre-dynastic times. By the first dynastic period, five thousand years ago, these had become pictures depicting gods, objects, and activities, to record, for instance, a deceased king’s victories, possessions, and divine favours. By the time of the pyramid texts, the Egyptians had also found graphemes for abstract ideas.

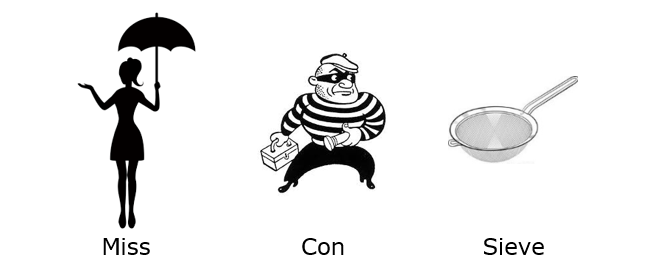

In time, the graphemes became ever more stylized, representing the sound of the name of the thing depicted. From there, the next step was what is called ‘pictorial phoneticism’, where the grapheme came to represent a syllable. This was a great innovation. For the Egyptian language contained many single-syllable words. And their pictures could be joined together to form longer words, without any reference to the original meaning of the syllables. It was as if, in English, we were to write the word ‘misconceive’ with three little pictures, one of a young lady (Miss), one of a burglar (con) and one of a sieve.

Then, in the nineteenth century BC, Hebrew slaves in Egypt made a breakthrough that was to change the world. The evidence is visible to this day, scratched in the walls of the turquoise mines of Wadi el-Hol, in Upper Egypt. [22] They took the hieroglyph idea one step further. Instead of using pictures to represent syllables, they used them to represent consonants. For instance, the word aleph meant an ox, and they drew a little ox head every time they wanted to represent the initial glottal sound of the word aleph. The word beth meant a house, and so they drew a little square house to represent the consonant b. And so on. It looked like this:

Some of the little pictures can easily be seen. Aleph looks like an ox head, beth like a little square house, daleth like a door, ḥeth like a fence, yodh like a forearm, and so on. (The letters called teth, samekh, and qof in later Hebrew are not included here because they are absent from the Wadi el-Hol inscriptions.)

Thus was born the aleph-bet. This early proto-Sinaitic aleph-bet didn’t have any vowels. Later though, some letters, like vav and yodh,were used as vowels.

Of course, over time, aleph-bets changed. During the time of the Israelite kingdoms, a thousand years later, the Hebrews had the paleo-Hebrew script, which was still recognizably the same pictures as the proto-Sinaitic ones above. Later still, during the Babylonian exile of the sixth century BC, they borrowed the more abstract square-shaped aleph-bet of Assyria. Modern Hebrew is still written in these Assyrian ‘square’ letters.

But the meaning of the names of the letters, their pictorial forms and what they represent, was not forgotten. As an old Hebrew teaching says, an illiterate man sees pictures on a written page—hand, fence, house—but does not discern their meaning. He is like the foolish person who looks at the world and sees objects and events but not the divine message within them.

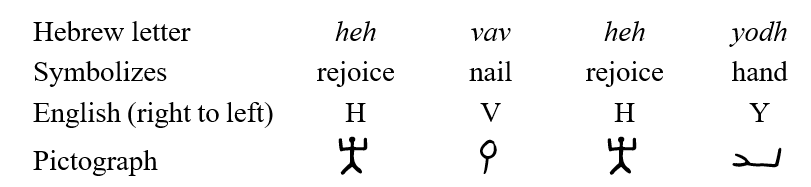

Knowing this, we can look at names and words as pictures and ask what they might represent. Let’s begin with the sacred name Yehovah. Stand in the shoes of an Israelite living in the time of the kingdom of Judah. Basic literacy was high among Jerusalem’s tradesmen and artisans. After all, the beauty of alphabetic writing was that one had to learn only twenty-two signs in order to read. As an eighth-century BC Israelite, you could read and write the name of Yehovah, for the name was still freely spoken and written. And, at that time, the three letters that make up the name were still much the same as when they were first invented nine hundred years before. It consisted, reading from right to left, of the following pictographs:

Now what would you make of such a sequence of signs? You might associate the rejoicing heh-figure, with the annual feasts in Jerusalem —Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot. These feasts, particularly Sukkot, were the high points of ancient Israel’s calendar. Everyone went to Jerusalem and ate and drank and danced and gave thanks to Yehovah for his goodness. That would be a natural link to make when looking at the letters of Yehovah’s name.

But what about the other two signs, the yodh-hand and the vav-nail? You might conclude that a hand and a nail represent a builder. And it might occur to you that Yehovah was the master-builder of the world. You might even know texts like Proverbs chapter eight, which tells how Yehovah ‘marked out the horizon on the face of the deep’ and ‘marked out the foundations of the earth’. And so you might conclude that the picture-letters of the name Yehovah tell how the God that Israel praises is the builder of heaven and earth.

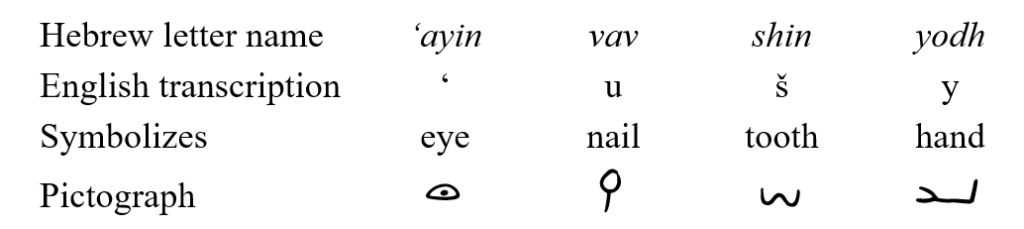

But what about the pictographs of the name Yeshua? What hidden meaning might they contain. They look like this.

How should this be interpreted? If our ancient Israelite had considered this name, then he might have thought that the hand and the nail, in the same position as in the name Yehovah, still represent the creator-builder. But what about the eye and the tooth? After some thought he would be reminded of the only Bible passage which speaks of an eye and a tooth together, the classical statement of the biblical principle of just judgement, the law of retaliation or ‘lex talionis’: you are to take life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise (Exod. 21:23–25).

The law of retaliation gets a bad press these days. Gandhi said, ‘If we practice an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, soon the whole world will be blind and toothless.’ But this misunderstands it. It is not about revenge but about just retribution. It is as much about limiting retribution as prescribing it. A person could not have all his teeth knocked out in revenge for one tooth. Nor could a thief be hanged for stealing a sheep, nor lose a hand for stealing a fig. Nor, on the other hand, could a murderer be let off with a caution. The punishment was to fit the crime so that justice was done in the sight of all.

The law of retaliation was the basis of divine justice. It was the law God followed. As he said to the Edomites, As you have done, so shall it be done to you (Obad. 1:15). God would repay each one according to his works. So, to the ancient Israelite, the symbols of Yeshua would depict the Creator-Builder who upholds just retribution. They might think of Joshua bringing divine wrath on the infanticidal Canaanites.

But when we look at the name in the light of the crucifixion, the hand and the nail take on a deeper meaning altogether. Yes, the one referred to is still the builder, the architect of earth, even the carpenter of Nazareth. But the hand and the nail point to the sufferings he bore. The eye and the tooth take on a deeper meaning too. Now they mean that, because of the sufferings of the hand and the nail, the law of retributive justice has been satisfied. The builder who suffered by the hand and the nail has borne the punishment of the guilty to satisfy the demands of the divine law.

SUMMARY: THE NAME OF JESUS

It is a fundamental idea of the Bible that there is power in names. Every Hebrew knew that, from the kohen gadol blessing Israel with the birkat kohanim to the wandering magician, muttering spells in the name of Yao.

And there is particular power in the personal names of God revealed to mankind. The first name revealed was Yehovah, the declaration of God’s eternal sovereign essence. With this name came great promises.

In every place where I cause my name to be called upon, I will come to you and bless you (Exod. 20:24).

They will put my name upon the Israelites and I will bless them (Num. 6:27).

I will call upon the name of Yehovah, so shall I be saved from my enemies (Ps. 18:3).

The name of Yehovah is a strong tower; the righteous run into it and are saved (Prov. 18:10).

Everyone who calls upon the name of Yehovah shall be saved (Joel 2:32).

But, later, another name was given which joined the name of Yehovah to a promise of salvation, the name Yehoshua. Because of this promise, it was a greater name. And it was revealed that this was to be the name of the Messiah promised to Joseph.

In time, Yehoshua was shortened to Yeshua. It was done without malice, and the new name retained the power of the old. And when the promised one appeared, this new name was announced as the greatest name of all.

You are to give him the name Jesus because he will save his people from their sins (Matt. 1:21).

Nor is there salvation in any other, for there is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved (Acts 4:12).

He has been given the name that is above every name so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow (Phil. 2:9–10).

Jesus is as much greater than the angels as the name he has inherited is greater than theirs (Heb. 1:4).

This name is superlative. It is 888, the number beyond perfection. It means shefo, the perfect one. Even in the apocopated form of the rabbis, seyo,it points to the lamb of God. Over the centuries, many have found it to be a strong fortress and a fount of blessing.

Two names were given to mankind for salvation. A great name and a greater name. But some forbade the speaking of the great name under the threat of a curse, and then forgot it altogether. As it is said,

Why does Israel pray in this world and is not answered? Because they have forgotten the shem meforash. (Mid. Teh. on Ps. 91:8)

But worse was to come. Having forgotten the great name, they twisted the greater name into an object of mockery. What help was left for them?

Eliezer ben Yehuda’s motive for reviving the Hebrew language was to fulfil Zephaniah 3:9: For then I will restore to the peoples a pure speech that they may all call on the name of Yehovah to serve him side by side. Yet the name of Yehovah is continually obscured—as adonai or HaShem—or twisted into Yahweh or Yahuwah. And the name Yeshua is still routinely shortened to Yeshu. To say Yeshua instead of Yeshu, as Ben Yehuda himself did, would be another important step in the modern Jewish reconciliation with Jesus.

[1] The best explanation for the formation of the Yehoshua is a portmanteau of Yehovah and the hiphil imperfect of yasha‘ (he saves)—Yeho[vah]+[yo]shia—the penultimate vowel morphing from –shia to –shua, as also in Elishua (2 Sam. 5:15; 1 Chr. 14:5) and Abishua (1 Chr. 6:35; 8:4; Ezra 7:5). But Gesenius thinks it comes from Yeho+yeshu‘ah (salvation). I thank Robert Gordon for his thoughts on this subject.

[2] The difference between the two forms is only in the Hebrew text. English Bibles simply call him Joshua.

[3] In the foreword to Ben Sira’s book, the grandson calls the grandfather Iesous ben Sirach.

[4] Greek (like French) has two u-vowels—u and ou. The latter was equal to Hebrew vocalic vav. Latin has only one u-vowel and so the unnecessary o dropped out.

[5] I refer the reader again to my Messiah ben Joseph, chapter 6.

[6] Philo, On the Change of Names 121.

[7] The fragmentary Hebrew text in the Bodleian library (MS.Heb.e.62; B XVII Verso) ends with yodh or vav-heh, indicating the words y’shuat yhvh.

[8] In 2013, a high-profile Israeli court hearing judged it to be authentic. See www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-artifacts/inscriptions/israel-antiquities-authority-returns-jesus-brother-bone-box-to-owner/

[9] See Ilan, Lexicon. In terms of popularity, Simon is first, Joseph second, Judah third, Eleazar fourth, Yohanan (John) fifth, Yeshua sixth. Bauckham, Eyewitnesses, chapter four, and Hachlili, ‘Hebrew Names’, have the same names, but rejig the order a little.

[10] Rokeaḥ, ‘Ben Stara’, 11, who says the original form of the text had Yeshua.

[11] The Vienna ms of Tosefta Ḥullin 2:22–24.

[12] Krauss, Leben Jesu, 250; Neubauer, ‘Jewish Controversy’, 24.

[13] Flusser, Jewish Sources, 15; similarly, Jesus, 6.

[14] Kutscher, Galilean Aramaic (67–70; 80; 89–96) says that in most places in Galilee and the rest of Palestine Jews were indeed able to pronounce the gutturals, but in a few places, such as Haifa, Beisan and Tibon, they generally did not pronounce them.

[15] Lauterbach, ‘Jesus in the Talmud’, 482.

[16] Although the letters digamma, qoppa, and sampi were obsolete by the mid-first millenium BC, they were retained for numerical purposes in later Greek.

[17] By way of example, the Midrash Rabbah on Genesis tells how, long ago, the letter yodh—with anumerical value of ten—was living content at the end of the name of Sarai. But when the Holy One made Sarai into Sarah and Avram into Avraham, the poor yodh was split into two letters heh, each with a numerical value of five. But yodh complained unceasingly to God of being so unjustly divided. So finally God prefixed yodh to the name of Hoshea, making Yehoshua. And he said to yodh: ‘Hitherto thou wast in a woman’s name and the last of its letters. Now I will set thee free in a man’s name and at the beginning of its letters.’ And then yodh was content (Gen. R. 47:1).

The tale is alluded to in Sanh. 107a, where David asks God to remove the Bathsheba incident from Scripture. God replies that if a single yodh complained so long over being removed, how much more could a whole passage not be removed.

[18] That the reference is to Nero is confirmed by some later mss., which have the number 616, equivalent to the Latin form, Nero Caesar, without the ‘n’ of Greek Neron.

[19] Φιλω ης αριθμος ϕμε.

[20] So Davidson’s Lexicon. That hasty lexicographer, Gesenius, thinks shafah means ‘bare’ or ‘naked’. But one must ask why so many people would call their sons ‘naked’. (Children are born naked, but parents don’t want them to remain naked.) Nor can one see why Isa. 13:2 would want a banner raised on a ‘bare’ hill (so NIV), when it would be better seen on an ‘eminent’ or ‘lofty’ hill.

[21] See shafan, ‘their eminence’(1 Chr. 5:12), yishpah (1 Chr. 8:16) and yishpan (1 Chr. 8:22), ‘he is eminent’.

[22] For the evidence that these inscriptions are indeed Hebrew, see Petrovich, World’s Oldest Alphabet. You can read a little about it at New Discoveries Indicate Hebrew Was World’s Oldest Alphabet.