It is generally recognized that Messianic belief at Qumran was not rigid. Some texts witness to two deliverers. Others are thought to have three: priest messiah, king messiah, and prophet [1]. I wish to suggest here that one text, so far understood as having three deliverers, has in fact four deliverers, and one of them is a Josephite Messiah.

1. 4QTESTIMONIA (4Q175)

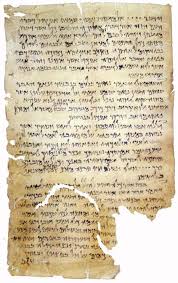

4Q175 (4QTestimonia) dates from the early first century BCE [2]. A well-preserved text, it comprises four separate sections, clearly demarcated by spaces and hook-shaped symbols, on a single page. The only damaged portion is the bottom right-hand corner, which leaves some gaps in the fourth testimony, but does not greatly hinder the understanding of the document as a whole. It is described as “a messianic anthology” and “a collection of fundamental biblical texts or ‘testimonies’, relating to messianic beliefs” [3]. Each of its four sections cites a Bible text ending with a curse, as follows: (1) Deut 18,18-19, the prophet like Moses; (2) Num 24,15-17, the star come out of Jacob; (3) Deut 33,8-11, the blessing of the Levites; (4) Josh 6,26, Joshua’s curse on Jericho, followed by a passage from the Joshua Apocryphon (4Q379) another document found at Qumran [4]. Here is the fourth passage.

At the moment when Joshua finished praising and giving thanks with his psalms, he said “Cursed be the man who rebuilds this city! Upon his first-born will he found it, and upon his benjamin will he erect its gates!” (Josh 6,26). And now an accursed man, one of Belial, has arisen to be a fowler’s trap for his people and ruin for all his neighbours. …will arise, to be the two instruments of violence. And they will rebuild […er]ect for it a rampart and towers, to make it into a fortress of wickedness […] in Israel, and a horror in Ephraim and Judah. […wi]ll commit a profanation in the land and a great blasphemy among the sons of…[…blo]od like water upon the ramparts of the daughter of Zion and in the precincts of Jerusalem [5].

Let us identify the dramatis personae. First there is Joshua. Martial man of God, Moses’ successor, king-killer, sun-stopper, razer of walls, he speaks his words at the conquest of Jericho and praises and thanks God. He is undoubtedly the hero of the fourth testimony, just as Moses, the Star from Jacob, and the Levitical Priest are the heroes of the first three. Juxtaposed to Joshua is the “accursed man” who is surely the villain of the piece. Then there are “the two instruments of violence” who may be either the “accursed man” plus an associate or — in line with Joshua’s words — the accursed man’s two sons. They are to rebuild a city, presumably the one Joshua destroyed. Clearly all these details were relevant both to the writer of the Joshua Apocryphon and to the writer of 4Q175 who cited them later. However, as my concern is not historical context but messianic typology, I shall focus on the four dominant heros.

Commentators are virtually unanimous that the figures of the first three testimonies — Moses, the Star, and the Priest — represent eschatological prophet, king, and priest figures [6]. It is easy to see why. The same three latterday heros appear in 1QS IX.10-11 by the same Qumran scribe. But little has been said about the fourth testimony. Dupont-Sommer and Cross say the villains represent enemies of the Qumran sect — a likely explanation — but say nothing about the Joshua figure himself [7]. In fact, in the entire corpus of scholarship on this passage, I know of no comment at all upon who or what Joshua might represent. Most commentators simply ignore the figure. Some even dismiss it as irrelevant [8].

It is unclear why the Joshua figure has been so overlooked. All four testimonies are identical in structure: hero figure, Bible verse and curse. If the first three represent eschatological deliverers, there would seem to be an a priori case for the fourth to be taken the same way. This would not only explain the Joshua figure itself, but would make sense of the entire document rather than just its first three-quarters. But for some reason it has not been suggested [9]. Nonetheless I propose that to interpret the fourth testimony in a manner consistent with the first three is eminently reasonable and produces a quite acceptable result, that is, an eschatological Joshua. This figure, like biblical Joshua, would be a warlike conqueror and trace his descent from Joseph and Ephraim. We might rightly call him War Messiah ben Ephraim ben Joseph.

Three further pieces of evidence may confirm this proposal: (i) the ‘Four Craftsmen’ baraitha of rabbinic literature; (ii) the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan to Exod 40,9-11; and (iii) messianic Joshua traditions.

2. FOUR CRAFTSMEN

The ‘Four Craftsmen’ tradition on Zech 2,3 appears in seven texts in two major variants. The earliest variant appears in Pesiqta Rabbati 15.14-15, Pesiqta deRav Kahana 5.9, and Song Rabbah 2.13.4, and is attributed to tannaitic period teachers [10]. Here is PesR 15.14-15.

The flowers appear on the earth (Song 2.12). R. Isaac said, “It is written: And the Lord showed me four craftsmen (Zech 2.3). These are they: Elijah, the King Messiah, Melchizedek and the War Messiah.”

A second variant, attributed to later authorities, appears in Suk 52b, Seder Eliyahu Rabbah 96, and Yalqut Shim‛oni on Zech 1,20 (568) [11]. Here is the Bavli version.

And the Lord showed me four craftsmen (Zech 2.3). Who are these four craftsmen? Rav Hana bar Bizna said in the name of Rav Shimon Hasida: “Messiah ben David, Messiah ben Joseph, Elijah, and the Righteous Priest.”

Of course both variants show the same figures [12]. Elijah is the same in each case. Messiah ben David is the King Messiah. The Righteous Priest is Melchizedek — in the Bible Melchizedek is always a priest (Gen 14,18-20; Ps 110,4) and there is supporting MS evidence [13]. That leaves Messiah ben Joseph to be identified with the War Messiah, a widely-held conclusion [14], supported by numerous texts [15].

The ‘Four Craftsmen’ tradition therefore features the same figures as I identified in 4Q175. In fact the earliest version of the ‘Four Craftsmen’ even presents the figures in the same order: prophet, king, priest, and Josephite War Messiah [16].

Diagram 1: The Four Craftsmen & 4Q175: Four Redeemer figures

| Redeemer Figures | ||||

| 4Q175 | Prophet | King Messiah | Priest | Joshua, War Messiah ben Joseph |

| Four Craftsmen. Variant A. | Prophet | King Messiah | Priest | War Messiah ben Joseph |

Such a correspondence of figures, number and order is striking. The likelihood of its being accidental is small: 1 in 24, to be precise, the probability of four names arbitrarily falling in a given sequence. (The introduction of other variables, such as number and identity of figures, would push the probability lower still [17].) This seems to corroborate our interpretation of 4Q175.

As for the relation between these texts, while direct dependence cannot be ruled out [18], it is much more likely that both derive from an earlier common source. If that is so, this source must have been already established by the time of 4Q175, allowing us to trace it back perhaps to the mid-second century BCE.

3. TARGUM PSEUDO-JONATHAN TO EXODUS 40,9-11.

Further confirmation of our proposal is provided by the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan to Exod. 40,9-11.

9. You shall take the anointing oil and anoint the tabernacle and all that is in it; you shall consecrate it for the sake of the crown of the kingdom of the house of Judah, and of the King Messiah who is destined to redeem Israel at the end of days. 10. You shall anoint the altar of burnt offerings and all its utensils, and consecrate the altar, and the altar will be most holy for the sake of the crown of the priesthood of Aaron and his sons, and of Elijah the high priest who is to be sent at the end of the exiles. 11. You shall anoint the laver and its base, and consecrate it for the sake of Joshua, your attendant, the head of the Sanhedrin of his people, by whose hand the land of Israel is to be divided, and of Messiah bar Ephraim, who will descend from him, and by whose hand the house of Israel will vanquish Gog and his horde at the end of days.

Its lucid polypartite format lends the passage a testimonial quality similar to 4Q175 and the ‘Four Craftsmen’. Its sections — three in this case — each pertain to different tribes or clans: Judah, Aaron, and Ephraim. Each section instructs that the tabernacle, its vessels and utensils should be anointed on behalf of representatives of one of these tribes. Each tribe has two sets of representatives: the first is, from the meturgeman’s viewpoint, historical; the second, eschatological.

The three eschatological anointed ones are explicitly messianic. They are the King Messiah from Judah and Messiah bar Ephraim from Joshua, who are to come “at the end of days”; and Elijah the (anointed) high priest who is to come “at the end of the exiles”. The presence of only three heros, instead of the previous four, is surely because ‘Elijah the high priest’ fulfils both the prophetic and priestly roles. These two roles probably merged in the period after the Priest Messiah fell from grace [19].

As for Messiah bar Ephraim, he is not merely Joshua’s antitype, as in 4Q175, but his descendant, who “proceeds” from him, as the King and Priest Messiahs do from Judah and Aaron. Being an Ephraimite, he is of course a Messiah ben Joseph. He is also a War Messiah, for he will conquer Gog and his hordes. The similarities to the previous passages are clear.

Diagram 2: Targum Ps.-Jon. to Exod. 40; The Four Craftsmen; 4Q175

| Redeemer Figures | ||||

| 4Q175 | Prophet | King Messiah | Priest | Joshua, War Messiah ben Joseph |

| Four Craftsmen. Variant A | Prophet | King Messiah | Priest | War Messiah ben Joseph |

| Tg. Ps.-Jon. Exod 40,9-11 | Elijah, the High Priest | King Messiah | (Elijah, the High Priest) | War Messiah ben Joshua ben Ephraim (ben Joseph) |

As regards dating, this text would appear to date from perhaps a century after 4Q175 [20]. It would therefore be earlier than the majority of the trimessianic midrashim below, as its simplicity would also seem to attest.

Therefore this targum, like the ‘Four Craftsmen’, confirms our interpretation of 4Q175 by showing that polymessianic testimonia with a Josephite War Messiah were not unusual in ancient Israelite literature. Indeed, it seems they were something of a genre [21].

4. MESSIANIC JOSHUA

Finally, there is evidence that Joshua was seen as a messianic type in post-biblical Judaism. The white bull born in 1 En 90.37-38 is widely recognized as a theriomorphic depiction of the Messiah [22]. Since this firstborn bull is followed in turn by a messianic wild ox or rem it appears that we have here the blessing of Joseph in Deut 33,17, the firstborn of his bull with the horns of a rem who will gore all the nations [23]. As Israelite literature habitually takes Deut 33,17 to represent Joseph, Ephraim, Joshua, or an eschatological Josephite-Ephraimite [24], it rather looks like the messianic bovid(s) of 1 En 90.37-38 depict an eschatological Joshua [25].

If we turn next to Sib. Or. 5.256-259, we find “one who shall come again from heaven, a man pre-eminent…noblest of the Hebrews…who at one time did make the sun stand still” [26]. Since Joshua is the only Bible figure to have made the sun stand still (Josh 10,12-14), the pre-eminent man seems again like an eschatological Joshua. Possible Christian influence hardly bears on the Jewishness of the text. For polymessianism and a Joshua Messiah, though known in Judaism, are unknown in standard Christian literature, whose Messiah is always a Judahite. If this writer was Christian, he was a thoroughly Jewish Christian [27].

Josephus tells how, during Nero’s reign, a self-styled prophet appeared on the Mount of Olives and predicted that, like Joshua, he would make the city walls fall at his command [28]. Since the Mount was renowned — from the time of Zech 14,4 — as the place of the Messiah’s appearing, Josephus’s prophet looks rather like an aspiring messianic Joshua [29].

A Targum on Exod. 17,16 says that the Amalekites will be exterminated for three generations: in the generation of this world (by Joshua), in the generation of the Messiah, and in the generation of the world to come [30]. Belief in a messianic Joshua, who like his forebears Joseph and Joshua would live 110 years, is also attested among the Samaritans [31]. Samaritan texts are relatively late, but Crown suggests that these ideas can be safely traced back to the second century BCE [32].

Rabbinic texts also portray the Messiah — especially ben Joseph — as a second Joshua. Some state that Ben Joseph-Ephraim will be Joshua’s descendant [33]. Indeed this appears to be a genealogical necessity. There being only one stirps from Ephraim to Joshua (1 Chr. 7.20-27), the Ephraimites had no princely line except through Joshua. Others present Ben Joseph as Joshua’s antitype by applying to both figures the Josephite rem of Deut 33,17 [34]. Yet others describe his military exploits in terms of Joshua’s destruction of Jericho with its unique falling walls. For instance, the midrash Tefillat Rav Shimon ben Yohai:

The bat-kol will say [to Messiah ben Joseph and his army]: “Just as Joshua did to Jericho and its ruler, so do to the nations of the world!”… They recite the shema. They will encircle Jericho, and the wall will collapse at once [35].

Likewise, in the midrash Pirqei Mashiah, Israel under Nehemiah ben Hushiel — a pseudonym for Messiah ben Joseph — recite the shema and the walls of the city fall [36]. The Roman-period Aggadat Mashiah contains a similar passage, the only difference being that the bat-kol addresses Ben Joseph’s Ephraimite army in the period between his death and the coming of Ben David.

And Israel goes to Rome. And a bat-kol proclaims a third time, “Do to her as Joshua did to Jericho!” And they surround the city and blow the trumpets, and the seventh time they raise a battle-cry: ‘Hear Israel! The Lord our God, the Lord is one!’ [Deut 6.4]. And the walls of the city fall [37].

A similar passage occurs in Pereq Rav Yoshiyahu, where the presence of Nehemiah ben Hushiel (Messiah ben Joseph) in the battle, though not stated, is implied, for he is resurrected after it [38].

Space permitting, one might cite the host of Messiah ben Joseph-Ephraim texts from all periods. For, as noted, genealogy requires the Ephraim Messiah to be Joshua’s son too. But enough has been said to make our case.

CONCLUSION

I suggest that the Joshua of 4Q175 represents a Josephite Messiah. Such an interpretation has the advantage of providing an explanation for the whole text, not simply the first three-quarters. It would seem to be confirmed by other polymessianic testimonia featuring a Joshua-Josephite Messiah, such as the ‘Four Craftsmen’ baraitha and the Tg Ps.-Jon. Exod 40,9-11. The likelihood of a common source for these texts allows us to suppose that these ideas were established before the writing of 4Q175 in c. 100 BCE. We also noted evidence of a continuous tradition of Joshua as a messianic type; some of these texts — particularly 1 En 90.37-38 — can also be dated to the mid-second century BCE ([39]).

As regards comparison with the War Messiah ben Joseph of rabbinic literature, it does not appear that the 4Q175 figure possesses the full endowments of the rabbinic one. There is no mention, for instance, of the key Messiah ben Joseph characteristic, violent death. Nonetheless both are Josephite War Messiahs, and so it would appear that the Qumran figure may well be an earlier form of the rabbinic one. This has implications for dating the development of Messiah ben Joseph.

For more on this subject, see my book Messiah ben Joseph (2016).

This is the pre-publication version of my paper “The Fourth Deliverer: A Josephite Messiah in 4QTestimonia”, which first appeared in Biblica 86.4 (2005) pp. 545-553. A pdf copy of this paper can be found in the Scholarly Articles page.

([1]) 4Q175; 1QS IX.10-11. They are by the same scribe.

([2]) For more on text and dating see F.M. Cross, “Testimonia (4Q175=4QTestimonia= 4QTestim)”, The Dead Sea Scrolls (ed. J.H. Charlesworth) (Tübingen 2002) VI B, 308.

([3]) G. Vermes, Dead Sea Scrolls in English (London 1962) 247; A. Dupont-Sommer, The Essene Writings from Qumran (Oxford 1961) 317.

([4]) The Joshua Apocryphon,or Psalms of Joshua, consists of 4Q378 and 379 (4QPsJoshua a & b). The 4Q175 citation is from 4Q379. As the Joshua Apocryphon includes Josh 6.26, the whole fourth testimony is taken from 4Q379. See C.A. Newsom, “The ‘Psalms of Joshua’ from Qumran Cave 4”, JJS 39 (1988) 56-73, who thinks it was not composed at Qumran (59); B.Z. Wacholder – M.G. Abegg, A Preliminary Edition of the Unpublished Dead Dea Scrolls (Washington 1991) III, 178-189; T.H. Lim, “The ‘Psalms of Joshua’ (4Q379 fr. 22 col. 2): A Reconsideration of its Text”, JJS 44 (1993) 309-312; C.A. Newsom, “4Q378 and 4Q379: An Apocryphon of Joshua”, Qumranstudien (ed. H.-J. Fabry – A. Lange – H. Lichtenberger) (Göttingen 1996) 35-85; E. Tov, “The Rewritten Book of Joshua as Found at Qumran and Masada”, Biblical Perspectives. Early Use and Interpretation of the Bible in the Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls(ed. M.E. Stone – E.G. Chazon) (STDJ 28; Leiden 1998) 233-256.

([5]) The English is from F. García Martínez, The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated. The Qumran Texts in English (Leiden – New York – Cologne 1994) 137-38; some of the textual reconstructions are omitted.

([6]) See e.g., D. Flusser, “Messiah: Second Temple Period”, EJ XI, 1409; G. Vermes, Jesus the Jew (London 1973) 96; Dead Sea Scrolls in English,248; G.J. Brooke, Exegesis at Qumran (JSOTSS 29; Sheffield, 1985) 309-310; F. García Martínez, Qumran and Apocalyptic (Leiden 1992) 174; “Messianische Erwartungen in den Qumranschriften”, JBTh 8 (1993) 203-207; F. García Martínez – J. Trebolle Barrera, The People of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Leiden 1995) 186; J.J. Collins, Apocalypticism in the Dead Sea Scrolls (London 1997) 71, 79; G.G. Xeravits, King, Priest, Prophet (STDJ 47; Leiden 2003) 57-59, 226-228. J. Lübbe’s view, that the text should be interpreted historically rather than eschatologically, has not commanded widespread consent (“A Reinterpretation of 4 Q Testimonia”, RevQ 12 [1986] 177-86).

([7]) Dupont-Sommer, The Essene Writings, 317; Cross, “Testimonia”, 309.

([8]) Collins, Apocalypticism, 79.

([9]) This may be due to the widespread view that Messiah ben Joseph is a late idea, developing out of Bar Kokhba’s defeat in 135 ce. See e.g., J. Hamburger, Realenzyklopädie des Judentums (Strelitz i. M. 1874) II, 768; J. Levy, “Mashiah”, Neuhebräisches und chaldäisches Wörterbuch (Leipzig 1876/1889) III, 270-272; A. Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah (s.l. 1883) 79, n. 1, 434-435; J. Klausner, The Messianic Idea in Israel (London 1956) 487-492; S. Hurwitz, Die Gestalt des sterbenden Messias (Zürich-Stuttgart 1958) 178-80; Vermes, Jesus the Jew, 139-140. In “Rabbi Dosa and the Rabbis Differ: Messiah ben Joseph in the Babylonian Talmud”, Review of Rabbinic Judaism 8 (2005) 77-90, I have tried to show that this idea is mistaken and present the case for ben Joseph being fully developed by the mid-first century ce. J. Heinemann has suggested that an existing militant Ephraim Messiah became a dying messiah by analogy with Bar Kokhba (“The Messiah of Ephraim and the Premature Exodus of the Tribe of Ephraim”, HTR 68 [1975] 1-15). Although such a view is not at odds with my conclusion in this paper, I feel it is not supported by evidence elsewhere.

([10]) PesK also attributes it to the fourth generation tanna R. Isaac (fl. 140-165) in the editions of Buber (S. Buber, Pesiqta de-Rav Kahana [Lyck 1868]) and Braude (R. Kahana’s Compilation of Discourses for Sabbaths and Festal Days [ed. W.G. Braude – I.J. Kapstein] [Philadelphia 1975]), but A.K. Wünsche (Bibliotheca Rabbinica [Leipzig 1885] III, 61) gives the second generation tanna ‘R. Eleasar’ (fl. 80-120). I have been unable to verify his Hebrew original. CantR2.13.4 attributes it to R. Berekiah in the name of R. Isaac.

([11]) Suk52b and the Yalqut tribute it to R. Hana bar Bizna in the name of R. Shimon Hasida, a little-known figure, probably of the late tannaitic period (Hag13b-14a; S. Frieman, Who’s Who in the Talmud [Northvale, NJ 1995] 291; Soncino Talmud, 722), whose teachings are known mainly through his third century disciple R. Hana (Frieman, Who’s Who, 84). SER gives no authority for the tradition.

([12]) A third variant of the ‘Four Craftsmen’ is found in the medieval compilation NumR14.1, where the priest is replaced by a Manasseh Messiah.

([13]) The Munich manuscript has “and Melchizedek”instead of “and the Righteous Priest” (R. Rabbinovicz, Variae Lectiones [Munich 1870] III, 170).

([14]) G.H. Dalman, Der leidende und der sterbende Messias der synagoge (Berlin 1888) 6; L. Ginzberg, “Eine unbekannte jüdische Sekte”, Monatschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 58 [1914] 421; Heinemann, “The Messiah of Ephraim”, 7; H. Freedman – M. Simon, The Midrash (London 1939) I, 698, n. 2; IX, 125 n. 3; M. Jastrow, A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Bavli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature (New York 1950)852 (“Mashiah”).

([15]) GenR. 99.2; Tan I.103a (§11.3); NumR14.1; AgBer§63 (Bet ha-Midrash [= BHM] A. Jellinek [Leipzig 1853-77] IV, 87); “Jelamdenu-Fragmente” §20 from Kuntres Acharon [Appended Document] to Yalq on the Pentateuch (BHM VI, 81); GenR 75.6; 99.2 applies the blessing on Joseph (Deut 33,17) to the War Messiah.

([16]) The identification of the prophets Elijah and Moses is attested in Jewish tradition. Yochanan ben Zakkai taught that the Holy One swore to Moses that, in the days of the Messiah, Moses and Elijah would come together ‘as one’ (DeutR3.17). More frequently Elijah was seen as a descendant of Aaron (Tg. Ps.-J. Exod 40,10; Pirkei Hekhalot Rabbati 40.2 in Batei Midrashot [ed. S.A. Wertheimer] [Jerusalem 1952-55] I, 134) and sometimes identified with Phineas (G.F. Moore, Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era [Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1927-30],II.358n; and e.g. PRE 66b). But at SER18 (ed. M. Friedmann [Jerusalem 1969] 97-98) the sages regard him as an Aaronite while Elijah himself claims to be a Benjamite, following 1 Chr 8,27.

([17]) Texts with two or three messiahs are numerous (cf. n. 21 below). NumR14.1 notes a view that there will be seven messiahs and tells of a Messiah from Manasseh. There was much scope for permutation.

([18]) Direct dependence need not necessarily mean the ‘Four Craftsmen’ following 4Q175. The latter may have been dependent on the former. I have suggested elsewhere that the ideas behind the ‘Four Craftsmen’ — as distinct from its tannaitic period expressions — date from temple times. This is seen from the prominent position of the Priest Messiah, who increasingly fell from favour during the century from the end of the Hasmonean dynasty (34 BCE) to the destruction of the temple (See Mitchell, “Rabbi Dosa and the Rabbis Differ”, 85-88).

([19]) See n. 18 above.

([20]) Given the long period of Pseudo-Jonathan’s redaction,each passage must be dated independently. This passage appears to date from between c. 30 BCE and 30 CE. The terminus a quo derives from the lack of a Priest Messiah, as opposed to a priest-prophet Elijah. This suggests a date after the Priest Messiah’s eclipse began, in the latter part of the first century BCE (cf. n. 18). The terminus ad quem is seen from the fact that increasing Jewish antipathy to Yeshua of Nazareth would have precluded the invention of a Yehoshua Messiah in the Christian period.

([21]) TestXIINaph5.1-8 (apotheosized Levi, Judah, and Joseph). Many midrashim feature ben Joseph, Elijah and ben David (the first five are given in Heb. and Eng. in D.C. Mitchell, The Message of the Psalter [JSOTSS 252; Sheffield 1997] 304-50): Aggadat Mashiah; Otot ha-Mashiah 7-9; Sefer Zerubbabel; Asereth Melakhim; Pirqei Mashiah 5-6 (Nehemiah ben Hushiel = ben Joseph; cf. n. 36); Pirkei Hekhalot Rabbati 39-40; Tefillat Rav Shimon ben Yohai (BHM IV.117-126); Pereq Rav Yoshiyyahu (BHM VI.112-116: 115); Saadia Gaon, Kitab al Amanat VIII.5-6 (The Book of Beliefs and Opinions [tr. S. Rosenblatt] [New Haven 1948] 301-304). The Zohar depicts Bar Joseph-Ephraim, Bar David and Moses (Faithful Shepherd) in trio (B’reshit, 234; Mishpatim, 483; Pinhas, 582; Ki Tetze, 62, cf. 48). Bimessianic texts are too many to list. I have cited some in “Rabbi Dosa” and in “Les psaumes dans le Judaïsme rabbinique”, RTL 36.2 (2005) 166-191.

([22]) A. Dillmann, Das Buch Henoch (Leipzig 1853) 286; M. Buttenwieser, “Messiah”, JE VIII, 509; R.H. Charles, The Book of Enoch (Oxford 1893) 258, n. 1; F. Martin, Le Livre d’Hénoch (Paris 1906) 235, n. 37; E. Isaac, “1 Enoch”, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (ed. J.H. Charlesworth) (London 1983/85) I, 5; C.C. Torrey, The Apocryphal Literature (New Haven 1945) 112; “The Messiah Son of Ephraim”, JBL 66 (1947) 266; J.T. Milik, The Books of Enoch (Oxford 1976) 45; B. Lindars, “A Bull, a Lamb and a Word: I Enoch xc.38”, NTS 22 (1976) 485.

([23]) Most commentators take Ethiopic nagar to mean the rem or wild ox. So Dillman, Henoch, 287-288; Charles, Enoch, 258-259; Martin, Le livre d’Hénoch, 235, n. 38; Milik, Books of Enoch, 45; M.A. Knibb, The Ethiopic Book of Enoch (Oxford 1978) II, 216; Torrey, “Messiah the Son of Ephraim”, 267.

([24]) In biblical times the bull’s horns are the symbol of the Ephraimites. They brag about having acquired horns for themselves (Amos 6,13) and sport iron horns to gore (ngh) the nations, as in Deut 33,17 (1 Kgs 22,11; 2 Chr 18,10). Deut 33,17 is applied to Joseph at GenR75.12; 86.3; 95.1; 95 (MSV); 99.2; ExodR1.16; 30.7; EstR7.11; LamRon 2.3 §6; to Joshua at GenR 6.9; 39.11; 75.12; NumR2.7; 20.4 (Israel under Joshua’s command); Yalq. on Deut. 33,17 (§959); to ben Joseph at MTann11.3 (ed. Buber, 102b); GenR75.6; 95 (MSV); 99.2; PRE22a.ii; AgBer §79; NumR 14.1; Zohar, Mishpatim, 479, 481, 483; Pinhas, 565, 567, 745; Ki Tetze, 21, 62.

([25]) Torrey, “Messiah Son of Ephraim”, 267, also sees the nagar-rem as Messiah ben Joseph.

([26]) O’Neill has shown that the “man pre-eminent” and the “noblest of the Hebrews” are the same person (J.C. O’Neill, “The Man from Heaven: SibOr 5:256-259.” JSP 9 [1991] 87-102: 88-91).

([27]) O’Neill notes the consensus that the author was a Jewish Christian, but proposes that the text is a Jewish oracle (“Man from Heaven”, 87, 100).

([28]) Ant. XX.viii.6 (ll. 169-70); War II.xiii.5 (ll. 261-63); the event is alluded to in Acts 21,38.

([29]) The Messiah was seen as present in Yhwh’s coming to the Mount in Zech 14,4 (Mitchell, Message, 212-14, 264-66); cf. Acts 1,11-12; Ma‘aseh Daniel (BHM V.117-130, 128). In temple times the Mount was known as har ha-meshiha, Mount of Anointing or — by Aramaic homophony — Mount of the Messiah (J. Braslavi – M. Avi-Yonah, “Mount of Olives”, EJ XII, 483; Rashi and Kimhi on Zech 14,4). Often the appearance of the Holy One on the Mount directly precedes the coming of the Messiah (Aggadat Mashiah 28-34; Sefer Zerubbabel 50; Pirqei Mashiah §5-6; Asereth Melakhim §4). Tg Cant8,5 and Codex Reuchlinianus of Tg Zech14,4 make it the place of the resurrection of the dead, a messianic function (cf. Mitchell, Message, 213).

([30]) British Museum; Add. 27031: cited by O’Neill, “Man from Heaven”, 93. O’Neill presents other evidence for Joshua as a messianic type (91-94).

([31]) See A.D. Crown, “Dositheans, Resurrection and a Messianic Joshua”, Antichthon 1 (1967-68) 85; “Samaritan Eschatology”, The Samaritans (ed. Crown) (Tübingen 1989) 266-292; J.A. Montgomery, The Samaritans (New York 1907) 244-249; J. Macdonald, The Theology of the Samaritans (New Testament Library; London 1964) 368.

([32]) Crown, “Samaritan Eschatology”, 292.

([33]) Tg Ps.-Jon. Exod 40,11. The meturgeman clearly did not hold the belief of E.G. Hirsch–B. Pick (“Joshua”, JE VII.282-284) and advanced by H.L. Strack–P. Billerbeck, Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud und Midrasch (Munich 1924/1928) II, 296, against Messiah ben Ephraim’s Joshuanic descent, that Joshua married Rahab and died without male issue. But the proof-texts cited in JE for this idea (Zeb. 116b; Meg. 14a; Yalq., Josh. §9) do not support the claim. (Yalq. Josh. §9 makes Rahab the ancestress of the Judahites of 1 Chr. 4.21.) E.E. Hallevy, “Joshua: In the Aggadah” (EJ X.266-267), notes Joshua’s marriage to Rahab (Meg. 14b) but not his lack of male issue. Male issue is probably implied at AZ 25a, where the filling of the nations by Ephraim’s seed (Gen. 48.19) is said to have taken place at Joshua’s conquest of the land (Josh. 10.3).

([34]) See GenR 6.9; 39.11; 75.12 with 75.6; 95 (MSV); 99.2; NumR2.7 with 14.1.

([35]) BHM IV.117-126: 123.

([36]) BHM III.70-74; Mitchell, Message, 325. The identification of Nehemiah ben Hushiel and ben Joseph is explicit at Otot ha-Mashiah §6-7 and Hekhalot Rabbati §39.1 and implicit at Sef. Zerub. 38-42; TRSY (BHM IV, 125); Pereq R. Yoshiyahu (BHM VI, 114-115); and Pir. Mash. §5.

([37]) Aggadat Mashiah 33 (BHM III.141-43; Mitchell, Message,304-07, 335-36). The writer’s desire for the destruction of Rome suggests an origin before the city’s fall in 455 ce. Jellinek suggests that the simplicity of the midrash also shows its antiquity (BHM III:xxviii).

([38]) BHM VI.112-16: 114-15.

([39]) The text is usually dated to c. 165 BCE; see Isaac, “1 Enoch”, 7; P.A. Tiller, A Commentary on the Animal Apocalypse of 1 Enoch [Atlanta 1993] 78-79.