Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion is one of the greatest monuments of Christian and European sacred music. In Holy Trinity, we perform it, or its sister work, Bach’s Saint John Passion, every year. But the Saint Matthew Passion was a flower that bloomed in a particular place at a particular time. And a little knowledge about its background and its native soil will help us to appreciate it better.

THE SAINT MATTHEW PASSION IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The roots of the German Passions lie in the earliest traditions of the Church. By the fourth century, if not before, it was customary to chant the Passion narratives, on the reciting tones, as part of the Holy Week liturgy. This chanted gospel was divided among four priests: one sang the words of the evangelist; another the words of Jesus; a third the utterances of various individuals – Pilate, Peter, the High Priest; and a fourth the exclamations of the crowd. By the ninth century, performance instructions began to emerge. The letter ‘c’ for celeriter or ‘quickly’ denoted the evangelist’s part. The letter ‘t’ for tenere or ‘sustained’ showed the words of Christ, to be declaimed with gravity. The letter ‘s’ for sursum or ‘lifted upwards’ denoted the other parts, showing that they were to be sung high and loud.[1] In time, more performance traditions and instructions emerged. These gradually developed into the Passion plays of medieval Europe.

After the tumult of the Reformation, the Passion was sung in Lutheran churches in the German tongue. It was the biggest musical event of the year, comparable perhaps to the annual Carol Service in modern anglophone churches. And, though solemn rather than festive, it was eagerly anticipated, the more so because of the Lenten tempus clausum, when no music was performed in city or church. In an age without muzak, this forty-day fast worked up an eager appetite for musical refreshment, whetted by civic pride in presenting a worthy Passion. For, in that age of faith, the annual remembrance of the death of Christ was a matter of high importance, city vying against city to represent the central mystery of the Christian faith. The German Passion grew vigorously, and began to take on the new musical forms of the sixteenth century.

THE LUTHERAN PASSION

The first development was the home-grown Lutheran chorale – a form of metrical plainsong – which found its way into the Passions as a choral comment on the biblical text. Later developments came from the Basilica of San Marco in fashionable Venice. Adriaan Willaerts, the sixteenth-century maestro di cappella, developed cori spezzati, antiphonal choirs, to exploit the Basilica’s vast architecture. Another San Marco maestro, Claudio Monteverdi, developed, in the early seventeenth century, the great innovation for solo voice, recitativo secco. In Monteverdi’s capable hands, recitativo gave birth to the sparkling new world of opera, which produced, in turn, aria and arioso. These Italian developments were soon incorporated into the German Passions, recitativo serving the declamation of the biblical text, cori spezzati enhancing the drama, aria and arioso serving for meditation.

With this increasingly potent mix, Passion settings were written by all the important German composers from the late sixteenth century on. Poetic dramatists of the time likewise composed libretti to enhance the Passion narrative, such as Der blutende und sterbende Jesus of Menantes and Der für die Sünde der Welt gemartete und sterbende Jesus of Brockes. The dynamic city of Hamburg led this development. It boasted the talents of Georg Philip Telemann, Johann Mattheson, Reinhard Keiser, and the young Georg Frideric Händel, who all wrote Passion settings for the city’s churches.

Elsewhere, of course, things were different. The conservative city of Leipzig had no opera or go-getting young freelancers. Instead, the Kantor of the Thomasschule, in the employ of the city council, was the city’s music director, responsible for music in the school and the churches. The city’s Passion music was dominated by the traditional monophonic chant until, in 1721, the Kantor, the learned Johann Kuhnau, finally presented a modern form of Passion with polyphonic music. Then, a year after this coup, Kuhnau died at the age of sixty-two.

LEIPZIG AND THE BACH PASSIONS

Kuhnau’s successor was the thirty-seven-year-old Bach.[2] He passed the rigorous theological exam with ease and moved with his family to Leipzig, where he remained for the rest of his life. The council, having tasted the prestige of a modern-style Passion setting, stipulated in his contract that he should compose a modern Passion setting for the Good Friday Vespers. And so, in the winter of 1723 to 1724, Bach wrote the St John Passion, probably incorporating parts of a St Mark Passion he had written some years before. About two hours in length, it is a fine work in its own right. But it is overshadowed by its successor, for, over the next three years, Bach wrote what his family always called Der große Passion, the ‘Great Passion’ according to St Matthew.

Its first performance took place in a small sort of way in the Thomaskirche on Good Friday, 11 April 1727.[3] One suspects that the performance was well below the level that we might expect to hear in a modern recording. Although they had a great musical director, musical expertise was lower than now and rehearsal time was short in the face of such complex music. The spatially-separated choirs stood in the north and south transepts of the church. Bach stood in the middle, holding it all together, just as he did when Johann Gesner saw him in 1738:

…singing with one voice and playing his own parts, but supervising everything and bringing back to the rhythm and the beat, out of thirty or even forty musicians, the one with a nod, another by tapping with his foot, the third with a warning finger, giving the right note to one from the top of his voice, to another from the bottom, and to a third from the middle of it – all alone, in the midst of the greatest din made by all the participants, and, although he is executing the most difficult parts by himself, noticing at once whenever and wherever a mistake occurs, holding everyone together, taking precautions everywhere, and repairing any unsteadiness, full of rhythm in every part of his body.[4]

The good citizens of Leipzig turned out in number to hear the first music in six and a half weeks. Jesus sang, surrounded by his “halo” of sustained strings (a device Bach borrowed from Keiser and Telemann), which departs from him only when he is finally God-forsaken. The choirs and orchestras began to play, the lovely music flowing from side to side in antiphonal waves – Sehet…Wen?…Den Bräutigam – while the Knabenchor, the schoolboys’ chorus, sang, from the back gallery, the chorale O Lamm Gottes unschuldig. As Bernstein said, “There is nothing like it in all of music.” But this was no entertainment. Heaven forbid! This was the vesper service of the holiest day of the Christian calendar, worthy to be adorned with the most beautiful music the city could muster. The council and the town’s wealthy burghers provided money for a musical offering on a scale not seen at any other time in the year.

As part of the solemn Good Friday Vespers, Bach would not have expected the Passion to be hailed by applause. But, sadly, it did not even meet with approval. Church-goers found it too operatic. The council greeted it with such a bedlam of carping and criticism that Bach was summoned to answer charges by the council secretary. This went on, year after year. Finally, in 1739, on being informed once again by the clerk of the council’s displeasure, Bach informed him, in bitterness of heart, that he did not “he did not care, for he got nothing out of it anyway, and it was only a burden to him anyway.”

Yet, over the years Bach refined his Saint Matthew Passion. It was performed again in 1729, then again in 1736 and 1742. Revisions were introduced. The short chorale concluding the first part was replaced by the great choral aria O Mensch, bewein. (This chorale, as Rifkin says, “probably originated as part of the Weimar Passion, and it also figured in the second performance of the St. John Passion before assuming its present location in the 1736 version of the St. Matthew Passion.”) Next, the spatial separation of the Cori was enhanced by separate continuo parts.

Finally, between 1743 and 1746, Bach wrote a fair copy in his own hand. In an age when music was written for immediate demands, without thought for the future, this is a remarkable score. The elderly Bach, knowing he might never hear it played again, took great pains over it. The Bible words are written in red. All is neatly laid out without confusion. Parts of the score, damaged, apparently by water, were laboriously restored. The score was laid up, with a set of performance parts, and, upon Bach’s death, entered a Sleeping Beauty existence of almost a century.

THE REVIVAL OF THE SAINT MATTHEW PASSION

True love’s kiss was bestowed by the young Felix Mendelssohn. The paths of the Mendelssohn and Bach families had crossed over many years. Mendelssohn’s great-aunt, Sarah Itzig Levy, had studied harpsichord with Wilhelm Friedrich Bach, commissioned works from C.P.E. Bach, and, with Felix’s father Abraham, she had acquired a large collection of Bach manuscripts. She was also an active member of the Berliner Singakademie,a choral association founded by Carl Fasch, a student of C.P.E. Bach, with deep Leipzig connections.[5] Fasch, inspired by the London Academy of Ancient Music’s performances of Handel, set up the Singakademie to perform the music of the old German masters, particularly Bach. Fasch was followed as director by another collector of Bach manuscripts, Carl Friedrich Zelter, who became teacher and mentor to the young Mendelssohn. And so, at the age of fourteen, Mendelssohn received from his grandmother a copy of the all-but-forgotten Saint Matthew Passion, made from the original manuscript in Zelter’s collection.

Shortly after, at the age of twenty, Mendelssohn borrowed Zelter’s podium to conduct the Saint Matthew Passion with the Singakademie, on 11 March, 1829, to great acclaim. He was hailed not only in Berlin but also in London, where the wealthy young Mendelssohn stayed as a guest of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and where he introduced the work in English as the St Matthew Passion.

However, such changes in musical culture had taken place since Bach’s time that Mendelssohn’s Passion performances differed from Bach’s in two important matters. First, whereas in Bach’s day the main spheres of musical employment were church and court, everything changed in the wake of the French Revolution. The aristocracy no longer kept private chapels, the churches were less prosperous, and wealth was increasingly in the hands of a burgeoning middle class. By the late eighteenth century, German musicians had turned to paid concertizing for a living, and concert halls were selected, or built, to hold as many paying listeners as possible. Zelter’s Singakademie, completed in 1827, was one such structure, where access to the musical treasures within were obtainable by the prosperous at the price of a ticket.

Second, whereas Bach’s instrumental and vocal forces were relatively modest – around thirty singers with a similar number of players – Mendelssohn’s forces were massive. The Singakademie chorus was a hundred strong on Fasch’s death in 1800, and larger still in Mendlessohn’s day. The deployment of singers was different too. Bach’s two choruses were led by eight concertati, one to each voice part, singing all the recitatives, arias, and choruses for their part, and they were joined by ripieni singers in the choruses. But the Singakademie, based on the London performances of Handel’s Messiah, had soloists singing only solos, and an amateur chorus who sang the choral parts without the soloists.

Mendelssohn’s singers were supported by a typical early nineteenth-century orchestra, numbering some seventy players. Their instruments, designed to fill a concert hall, had a stronger timbre than those of Bach’s day. The violin’s bass bar, fingerboard, neck, and bow had been modified to allow increased string tension and fuller sonority. The organ was larger and the oboe was taking its modern form. Performance pitch had changed too, to produce a more brilliant sound. The Kammerton pitch standard in Bach’s Germany was around A 420.[6] But by Mendelssohn’s time tuning was on the rise. His London visits saw the Philharmonic Society go from A 433 in 1820 to A 453 by 1846, while Covent Garden crept as high as A 456 the following decade, before A 440 became the international standard in the twentieth century.

Mendelssohn’s Berlin and London Passions were therefore quite different from Bach original. Louder, bigger, and stronger, with payment for entry, they were concert pieces rather than church liturgy. For all Mendelssohn’s piety, and for all the devotion of his audience, the route from the Thomaskirche to the Singakademie had changed Bach’s masterpiece from worship to entertainment.

RESTORATION OF THE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA

In the decade after Mendelssohn’s triumph, François-Joseph Fétis was appointed director of the Conservatoire Royale de Bruxelles. Fétis, though little-remembered as a composer, was a first-rate musicologist. His publications on music history, particularly of the Renaissance, engendered the science of comparative musicology.[7] Yet more influential still was his large collection of musical instruments which he bequeathed to the Conservatoire. And when, five years after Fétis’s death, a magnificent collection of Asian instruments was presented to King Leopold II by the Bengali Rajah Sourindro Mohun Tagore, the two collections were amalgamated by royal decree and kept at the Conservatoire. A curator was appointed, Victor-Charles Mahillon, who set about his work with vigour. Aided by royal funds and diplomatic connections, he bought instruments from all over the world, restoring them in Brussels, and adding them to the collection until it numbered well over 3,000 instruments. Meanwhile, Fétis’s successor at the Conservatoire, François-Auguste Gevaert, began, in the early 1880s, to give concerts on these instruments with the professors and students of the Conservatoire. These concerts were a great success not only in Brussels, but also in London, where Gevaert ‘s ensemble visited.

One Conservatoire student at the time was Arnold Dolmetsch, the son of a family of French instrument-makers. The Conservatoire collection awoke in Dolmetsch a passionate interest in the revival of ancient instruments. Moving to England to study at the Royal Academy of Music, he continued his researches at the British Museum. Finally, he established his own workshop at Haslemere in Surrey, specializing in instruments of the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries. His book, The Interpretation of the Music of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries (1915), and the Early Music Festival, which he established at Haslemere, led to a Europe-wide awakening of interest in the instruments of Bach and his contemporaries. Admired in his own lifetime by Elgar and Walton, Dolmetsch’s work eventually led to the pioneering performances of David Munrow in the 1970s and to the beginnings of the movement for historically-informed performance.[8]

Meanwhile Brussels had not stood still. The ever-expanding Conservatoire instrument collection was gathered, in the year 2000, from fifteen separate locations into its own superb venue, the art deco Old England, upon the Mont des Arts, to become the Musical Instrument Museum. With over 8,000 instruments, it is one of the finest organological collections in the world, continuing to inspire the building and performance of ancient instruments throughout Europe. The Conservatoire has become a world centre for the study of historically-informed performance. Functioning in English as much as in French and Flemish, with an international body of tutors, it attracts students from all over the world seeking to specialize in pre-modern music.

The result has been that, after more than a century’s research, the instruments of Bach’s day have been entirely reconstructed. Baroque violins and cellos, with low-tension gut strings, sound less brash than their modern counterparts. Wooden flutes are more limpid; recorders, violas d’amore and violas da gamba add their unique sound. The range of eighteenth-century oboes are a particular feature of the Baroque sound. The Passions require three: the oboe in C, the oboe d’amore in A, and the long-lost oboe da caccia in F. Nikolaus Harnoncourt tells of finding the last surviving oboe da caccia in a Stockholm museum.[9] Built by Eichentopf in Leipzig in 1724, the semi-circular oboe in F with a large brass bell corresponded exactly with the instrument required in Bach’s scores. It is now produced in perfect detail by instrument makers such as the celebrated Belgian oboist Marcel Ponseele.

Not only have the instruments been restored, but also the skills to play them. Quantz’s flute book, Leopold Mozart’s Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing, and other works preserve details of Baroque styles of playing. A lighter style altogether, with portato bowing and breathing, it is yet strongly rhythmic, with firm down-bows on the accented beats. Students of this style discuss, with erudition, Bach’s tabula accentum and the execution of the schleifer and the doppelt-cadence. Meanwhile, a modern ‘Baroque’ pitch standard of A 415 permits a sound one degree less strained, especially for sopranos and tenors, though the bass soloist can be challenged by the low D flat in the Johannes-Passion.

With restored instruments and techniques, the characteristic sound of the Baroque orchestra – double-reeds and veiled strings – has re-emerged from oblivion. Bach’s music surely sounds best on the instruments for which it was written. Such an ensemble should be sought by those who can obtain it.

THE VOCAL FORCES OF BACH’S PASSIONS

However, while the Baroque orchestra has been restored, Bach’s intended vocal forces are a thornier matter altogether, particularly in the light of a recent scholarly trend toward Bach minimalism.

The paper that Joshua Rifkin read to the American Musicological Society in 1981 was shouted down amidst a chorus of catcalls when he suggested that the surviving parts for the Matthäuspassion – eight vocal scores, one for each voice part in each of the two Cori – were originally sung by only one singer each.[10] The Great Passion was designed, he said, for two SATB quartets. Yet, despite this unenthusiastic reception, Rifkin’s views have spread and become influential. Daniel Melamed, for instance, says that ‘those who doubt the validity of this interpretation’ do so ‘for ideological or personal reasons.’[11] Paul McCreesh, who has released a recording of the Passion with only eight singers in the two Cori, is bolder still, declaring:

Parrott and Rifkin have had to endure a huge amount of scorn from other so-called scholars; yet most of the scholarly counter-argument has been utterly pathetic. So all I would say to those who can’t accept the arguments, is please go ahead and prove where we are all wrong.[12]

Thus, to answer McCreesh’s brash assertions, we must address the minimalist hypothesis. As presented by Melamed, the argument begins with the Johannespassion.[13] Its surviving parts comprise four concertato parts – soprano, alto, tenor, and bass – containing all solos and choruses for their part, plus four ripieno scores, containing only choruses. The concertati therefore sang everything and were joined in the choruses by the ripieni. This, all agree, was standard eighteenth-century practice.

Then Melamed notes that in ‘Mein teurer Heiland’, a bass aria with SATB chorus, the aria melody is in the bass concertato part, while the chorus parts appear in the other seven parts. He therefore concludes, probably correctly, that the concertato parts were for one singer each – nobody shared with them – because the bass concertato part does not contain a chorus part for ‘Mein teuer Heiland’ that a ripienist sharing the part might sing. From this, he deduces that the ripieno parts were also intended for one singer each. Then, on the basis of this deduction, he assumes that the eight surviving parts of the Matthäuspassion were likewise sung by one singer each.

But this is a double non sequitur. If the concertato parts of the Johannespassion were designed for one singer each, it does not follow that the ripieno parts were designed for single voices. The parts are big enough for several singers to read with ease. And, clearly, in choruses, many voices are better, both for drama and for balance. For, while a single ripieno bass might struggle against double voices on the upper parts, the imbalance would be less marked with three or four singers to a part. Further, even if this deduction were valid, it still would not follow that ‘Mein teurer Heiland’ shows the Matthäuspassion parts were for one singer each. For there is no analogous aria in the latter Passion where a soloist is accompanied by singers from the same Coro.

Melamed’s second piece of evidence is that the vocal parts of both Passions contain no performance instructions as to who should sing what. There is no indication that arias or recitatives are to be sung by the concertati, nor that the ripieni should join in the choruses and cease afterward. Why, he asks, did the copyist not insert the words ‘Christus’, ‘Evangelist’, or ‘Chorus’ to show when each should sing or be silent? This absence, he concludes, shows that each part was designed for only one singer, for otherwise the ripieni would not know when and when not to sing.

But, in reply, why would the ripieni require such rubrics to guide them? Bach’s singers recognized arias, recitatives, and choruses well enough. Everyone knew their roles. The concertati, one imagines, would know their arias; the ripieni knew their place. And the work had been rehearsed. Therefore the question is not, ‘Why did Bach and his copyists not specify who sang what?’ The question is rather, ‘Why would they spend time spelling out the obvious?’

Therefore the minimalist arguments are hardly watertight. Further, they fail to answer important considerations that weigh in against them.

First, if the Saint Matthew Passion was designed for only eight singers, why did Bach specify such a large orchestra. The minimum number of players is twenty-four, as even McCreesh agrees, though thirty or so is a likelier total.[14] Was Leipzig’s Herr Hofcompositeur so ignorant of the principles of orchestration that he specified a thirty musicians to accompany eight singers? Or had he perhaps a generous orchestral budget, to be spent or confiscated, but only a miserly allocation for singers? Surely not. Against his twenty-four-piece orchestra, McCreesh sets eight powerful, well-trained, modern, professional singers – stronger singers than Bach ever had – yet one can hear that they are straining to be heard over the orchestral tutti. For a budget-conscious church musician to hire so many players for eight singers seems very strange. Such an orchestra was surely designed to support corresponding vocal forces, that is, an absolute minimum of twenty-four singers. The parts were large enough for this.

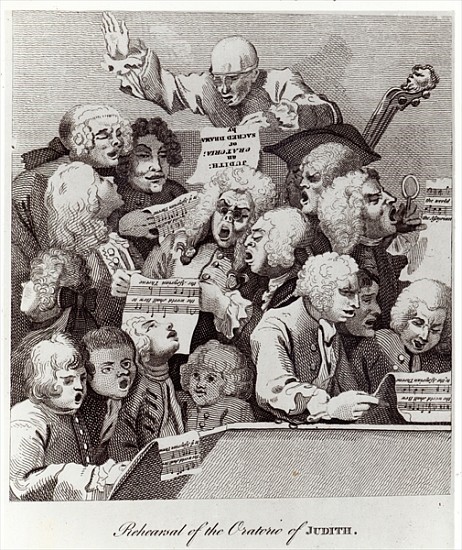

Second, in Bach’s day three or four singers to a part was ubiquitous practice, for the time and labour involved in hand-copying parts meant that only the minimum number were made. Here is Hogarth’s illustration of the rehearsal of the oratorio Judith by Thomas Arne.[15]

The musical director, head in score, gesticulates wildly. Below, sixteen singers share five parts. At top left, three singers share one. To their right, three more share another. At bottom left, four singers – one with head thrown back in rapture – share a part while, at bottom right, three more share another.

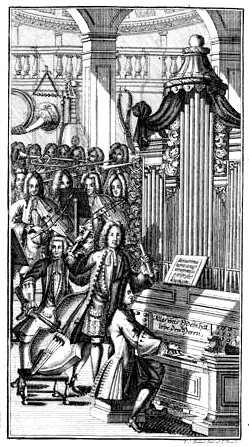

The same thing is seen in the frontispiece to J.G. Walther’s Musikalisches Lexicon,published in Leipzig in 1732, when Bach was at his most industrious. The musical director stands beside the organist, sharing the same copy. Behind them, four string players all read from a single music stand. Since Walther (1684–1748) was not only Bach’s exact contemporary, but also his cousin, there is every reason to suspect that this Leipzig woodcut depicts the practice in Bach’s churches. Indeed, the galleries look like the galleries of the Thomaskirche and the leading figure looks very like Bach himself, beating time with his characteristic scroll of music paper.

The issue, therefore, is not whether Bach could have had multiple singers on one part. He could. Nor is there any question of whether he would use multiple singers if he could get them. He told the Council explicitly, in his Short but most necessary draft for a well-appointed church music, that, while one singer to a part was an absolute minimum, his preference was three to four singers to a part. The key issue then is whether he would have had such forces in the Thomaskirche on Good Friday. The answer, again, is that he would. He had oversight of the city’s four churches – St Thomas, St Nicolas, St Matthew (the New), and St Peter – in each of which he had his a quartet of one singer to a part.[16] He writes of these four quartets that the first (St Thomas) can sing whatever he gives them, the second (St Nicholas) is competent, the third (St Matthew) is weaker, and the fourth (St Peter) is useless.[17] In addition, he had some fifty-five boys from the Thomasschule. The best of these might sing in the two choruses, while others would sing in the Knabenchor. Since the Passion took place in only one church each year, all these forces were at his disposal. He had a prefect, responsible for the weekly worship in St Matthew and St Peter, who would also have been available as a singer or musician on Good Friday. He also had his sons, Wilhelm, Carl, and Johann, who were fine musicians. His musical cousin, Johann Gottfried Walther, might have been persuaded to help, along with former Thomasschule choristers returning to Leipzig for Easter.

Thus, with a mix of paid and unpaid singers of varying abilities, Bach assembled his Great Passion. His best quartet of church singers, from the Thomaskirche, provided the Coro I concertati. The second-best quartet, from the Nikolaikirche, were concertati for the less-demanding Coro II. To these he added, as ripieni, his singers from the other churches and elsewhere. One chorus was placed in the north transept gallery, the other in the south. Some would sing tunefully and accurately; others less so, lending an air of genuine unpleasantness to the turba choruses. Thus, with some three or four singers reading each of the eight parts, the total number of singers in the two Cori was between twenty-four and thirty-two, just what might be expected to balance the orchestra. Finally, he placed his Knabenchor in the back gallery of the church for the sensational chorale line of Kommt, ihr Töchter. The boys would then sing the chorales from the same location, and the great choruses with a single soprano line, O Mensch, bewein and Wir setzen uns.

Such would have been Bach’s practice in the Thomaskirche. Of course, any modern attempt to reconstruct it faces challenges. By far the greatest is the architectural challenge of finding, outside Leipzig, a performance space like the Thomaskirche or Nikolaikirche, with their rear and transept galleries, each capable of holding some two dozen singers and musicians.

SAINT MATTHEW PASSION: SACRED SONG FOR SACRED SERVICE

The historically-informed performance movement has successfully restored the sound of Bach’s orchestra, and scholarship has enabled a better appreciation of Bach’s vocal deployment. The sound of a pre-Mendelssohn Bach orchestra is now familiar. Yet Mendelssohn’s revival changed not only the sound of Bach’s masterpiece but also its setting. And it is fair to say that, while some note and lament the lack of a liturgical setting, little attention has been given to restoring it.[18] The Passion is still routinely presented as a concert event outside Good Friday Vespers; entry is for the price of a ticket; the organizing bodies are concert halls or choral societies rather than churches; the motives are commercial. Objectively-speaking, this enjoyment of liturgy for art’s sake can seem strange.[19] Worldwide, the musical treasures of Christian liturgy –passions, masses, requiems, cantatas, Te Deums – have become high-brow entertainment, to be aesthetically sipped along with the intermission sherry. It is as if, a hundred years from now, people should pay to attend prayer book readings, applauding the beauty of the diction, but failing to understand the text’s meaning or intended purpose.

Yet, though strange, it is comprehensible. For we still inhabit Mendelssohn’s context. Churches lack disposable funds and do not spend what they have on what all now see as ‘cultural’ events. City councils have little concern to celebrate the church’s holy days. Concert-going is still a main source of musical income and, since the Passion requires professional musicians, we look to concertizing to pay them. And, finally, when performed outside Germany, the language-barrier means that Bach’s sacred vocal works may be more appreciated as music than as liturgy.

Yet any real revival of Bach’s music requires its return to the context for which it was written. What does this mean in practice?

First, it means that, as in Bach’s day, the initiative for the performance begins not with an impressario or a promoter, but with a church Director of Music, responsible for weekly worship, gathering the available forces to organize a service to dignify the solemnity of Good Friday.

Second, as a church service, entry must be free. Funding must therefore come from sources other than ticket sales. In Bach’s day, these sources were fourfold: the city council, wealthy burghers, programme sales, and a freewill offering at the event. In our time, corporate sponsorship may replace the city council. But donations from members of the community, programme sales, and freewill offerings remain possible. These may not generate the funds of a ticketed performance. But profit is not the primary motive. If enough is raised to cover costs, then one is content.

Third, it should be essentially a community event. One will therefore worry less about male altos and sopranos, if female altos and sopranos are keen to join in. One will not fret over architectural limitations, but find other ways to present the cori spezzati. The community will support, develop, and promote the Passion as a gift to all who would wish to come. It will attract people not only from the immediate congregation, but many others who love Bach, especially Germans, Flemings, and Danes, to whom the German language is readily accessible, and who have deep cultural links with the Passion. This will promote inter-community relations and heal ancient racial wounds.

All these things should be done, not neglecting the fruits of the historically-informed performance movement and modern musicological scholarship, but employing a fine Baroque orchestra, with singers, including children, deployed according to eighteenth-century practice. This is what we seek to do in our Matthäuspassion. With an excellent Baroque orchestra, hand-picked from graduates of the local conservatoires, playing period instruments at A 415, with solo singers serving as concertati and children in the Knabenchor, with liturgical performance on Good Friday and free entry to all, we seek to restore to Bach’s masterpiece not only it authentic colours, but its authentic context.

CONCLUSION

Let’s conclude. Bach’s Matthäus-Passion, like all eighteenth-century German Passions, grew out of an ancient ecclesiastical tradition in which the Passion of Christ was presented in a service of worship on Good Friday. Entry was free to all, the costs of the event being defrayed by the City Council and its wealthy citizens. But 19th century revivals of the Passions introduced much more massive forces and turned the Passions into concert-hall repertoire.

The historically-informed performance movement has done much to restore the sound of the Baroque orchestra. But less has been done to restore the original liturgical and communal context of Bach’s Passions. It is time that this distortion too was reversed, and that the Passions are sung again in their original context as acts of divine worship on Good Friday.

Bibliography

Applegate, C.

2005 Bach in Berlin: Nation and Culture in Mendelssohn’s Revival of the St. Matthew Passion (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

Bitter, C.H.

1865 Johann Sebastian Bach. 2 vols (Berlin: Schneider).

Burton, A. (ed.)

2002 A Performer’s Guide to Music of the Baroque Period (London: ABRSM).

Butt, J.

2010 Bach’s Dialogue with Modernity (Cambridge University Press).

2002 Playing with History – the historical approach to musical performance (Cambridge University Press).

1994 Music Education and the Art of Performance in the German Baroque (Cambridge University Press).

David, H.T., Mendel, A., Wolff, C. (eds),

1998 The New Bach Reader (New York: Norton).

Dolmetsch, A.

1915 The Interpretation of the Music of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries (London: Novello).

Fétis, F.-J.

1837 Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie générale de la musique. 3 vols(Brussels: Meline, Cans & Comp.).

1869-76 Histoire générale de la musique. 5 vols(Paris: Didot).

Green, J.D.

2000 A Conductor’s Guide to the Choral-Orchestral Works of J.S. Bach (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow).

Harnoncourt, N.

1997 The Musical Dialogue (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus).

Marcel, L.-A.

1996 Bach (Paris: Seuil).

Melamed, D.R.

2005 Hearing Bach’s Passions (New York: Oxford University Press).

Neumann, W. and Schulz, H.-J. (eds)

1963 Bach-Dokumente. 3 vols. (Kassel: Bärenreiter).

Parrott, A.

2000 The Essential Bach Choir (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell).

Quantz, J.J.

1752 Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (Berlin).

Rifkin, J.

2002 Bach’s Choral Ideal (Dortmunder Bach-Forschungen 5; Dortmund: Klangfarben Musikverlag).

1982 ‘Bach’s Chorus: A Preliminary Report’, The Musical Times 123, pp. 747-754.

1975 ‘The Chronology of Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion’, The Musical Quarterly 61, pp. 360–87.

Schweitzer, A. and Gillot, H.

1905 J.S. Bach, le musicien-poète (Leipzig, Breitkopf & Härtel).

Sherman, B.D.

2003 ‘Conducting early music’, in J.A. Bowen (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Conducting (Cambridge University Press), pp. 237-48.

Spitta, P.

1873-80 Johann Sebastian Bach (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel).

Stauffer, G.B.

1997 ‘Changing issues of performance practice’ in J. Butt (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Bach (Cambridge University Press), pp. 203-17.

Steinberg, M.

2005 Choral Masterworks (Oxford University Press).

Walther, J.G.

1732 Musikalisches Lexicon (Leipzig: Wolfgang Deer).

Discography

Cleobury, S. (dir.)

1994 Bach, Matthäus-Passion (Brilliant Classics).

Eliot Gardiner, J. (dir.)

1989 St Matthew Passion (Deutsche Grammophon)

Herreweghe, P. (dir.)

2012 Matthäuspassion (Youtube.com)

McCreesh, P. (dir.)

2003 St Matthew Passion (Deutsche Grammophon).

[1] N. Harnoncourt, The Musical Dialogue (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus, 1997) pp. 166-67.

[2] The council first offered the post first to Telemann and then to Graupner. Telemann used the offer to secure better terms in Hamburg, while Graupner was unable to obtain his release from Hesse-Darmstadt. Another favoured candidate, Fasch, withdrew his candidacy before an offer was made. The council then appointed Bach, concluding, “Having failed to secure the best, we must now settle for the mediocre.” He endured the Council’s ingratitude throughout his time in Leipzig. The promised salary of 1000 thalers a year never fully materialized. The post as musical director in the University, to which he had hoped to be appointed, was given to Görner. The council merchants objected to his time spent on music and insisted that he teach the boys Latin, a duty he escaped only by paying a deputy at his own expense.

[3] The now widely-accepted first performance date of 1727 follows J. Rifkin, ‘The Chronology of Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion’, The Musical Quarterly 61 (1975) pp. 360–87.

[4] Cited in H.T. David, A. Mendel, C. Wolff (eds), The New Bach Reader (New York: Norton, 1998), entry 328.

[5] Carl Fasch (1736-1800) was the son of Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688-1758), who studied under Kuhnau at the Leipzig Thomasschule, founded a Collegium Musicum in the city, and applied for the Kantor’s position at the same time as Bach, then withdrew his candidacy.

[6] J.J. Quantz, Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (1752), speaks of a fistful of pitch standards, including Cornett-Ton, Chorton, Hochkammerton, and Tiefkammerton. However, since the woodwinds could not retune like strings (and voices), their (Hoch-) Kammerton effectively prevailed.

[7] Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie générale de la musique (Brussels: Meline, Cans & Comp., 1837); Histoire générale de la musique (Paris: Didot, 1869-1876).

[8] Others played significant roles in the early-music revival. The Bach biographies of C.H. Bitter (Johann Sebastian Bach, 1865) and P. Spitta (Johann Sebastian Bach, 1873-80) published the text of Bach’s ‘Short but most necessary draft for a well-appointed church music’ [Kurzer, jedoch höchst nötiger Entwurf einer wohlbestallten Kirchenmusik] in W. Neumann and H.-J. Schulz, Bach-Dokumente, Vol I (Leipzig and Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1963)], revealing the modest vocal and instrumental forces at Bach’s disposal. Albert Schweitzer, too, called for restraint in the forces employed in Bach performance and for a return to the organ tone of the eighteenth century (J.S. Bach, le musicien-poète,1905).

[9] Harnoncourt, Musical Dialogue, pp. 60-62.

[10] Rifkin, ‘Bach’s Chorus: A Preliminary Report’, The Musical Times 123 (1982), pp. 747-754.

[11] Melamed, Hearing Bach’s Passions, p. 5.

[12] McCreesh, Saint Matthew Passion, CD booklet, p. 17.

[13] Melamed, Hearing Bach’s Passions, pp. 19-32.

[14] McCreesh, Saint Matthew Passion, CD booklet, p. 16. The addition of two continuo bassoons and a third player to each violin part (Bach’s expressed preference in his ‘Short but most necessary draft’) would bring the total from twenty-four to thirty, not including the gambist who may perhaps have doubled on another instrument.

[15] Judith, by Thomas Arne and Isaac Bickerstaffe, was premiered in Drury Lane in 1761.

[16] The fact that the minimalists speak only of the first two churches is, one imagines, part of the ground for their ‘eight singers’ theory (Melamed, Hearing Bach’s Passions, pp. 7, 42, 60).

[17] These details are all contained in Bach’s ‘Short but Most Necessary Draft for a Well-Appointed Church Music’ submitted to Leipzig Council in August 1730.

[18] Steinberg, Choral Masterworks, pp. 3-5; Melamed, Hearing Bach’s Passions, pp. 7-10.

[19] Though apparently not to Richard Dawkins. Although he thinks the passion narrative is ‘sadomasochistic’, ‘viciously unpleasant’, and ‘tortuously nasty’, he included ‘Mache dich, mein Herze, rein’ in his Desert Island Discs selection, saying that he could not understand that anyone might find this odd.