There are three references to Messiah ben Joseph in the Talmud. They all appear on a single page of the Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 52. This paper discusses the interpretation and dating of these texts.

One of the most compelling figures in rabbinic literature is Messiah ben Joseph, the latterday Ephraimite king who dies in eschatological warfare with monstrous foes. There are references to him – by name or pseudonym – in a host of texts from the first and second millennia CE. But the three references in the Babylonian Talmud are particularly important because of their antiquity. A single page of the Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 52, has the distinction of containing these earliest known references to Messiah ben Joseph. This paper discusses the interpretation and dating of these texts.

1. SUK. 52A (TOP): MESSIAH OR THE EVIL INCLINATION

Here is the first passage. The original is in both Hebrew and Aramaic. The Aramaic passages have been rendered in italics.

“And the land shall mourn family by family apart. The family of the house of David apart and their women apart” (Zech. 12:12). They said: Is not this an a fortiori conclusion? In the age to come, when they are busy mourning and no evil inclination rules them, the Torah says, “the men apart and the women apart.” How much more so now when they are busy rejoicing and the evil inclination rules them. What is the cause of this mourning? Rabbi Dosa and the rabbis differ. One says: “For Messiah ben Joseph who is slain”; and the other says: “For the evil inclination which is slain.” It is well according to him who says “For Messiah ben Joseph who is slain”, for this is what is written, “And they shall look upon me whom they have pierced, and they shall mourn for him like the mourning for an only son” (Zech. 12.10); but according to him who says “The evil inclination which is slain”: Is this an occasion for mourning? Is it not an occasion for rejoicing rather than weeping?

The text is composed of several layers. There are, of course, the Bible texts. Then there are remarks by rabbinic commentators in both Hebrew and Aramaic. The Hebrew passages represent oral traditions deriving from Israel in the tannaitic period, before 200 CE. The Aramaic passages are the Babylonian redactor’s comments and date from the amoraic period, between c. 200 and 450 CE. As Kutscher says: “MH [Mishnaic Hebrew] was a living language in Palestine only until about 200 CE, the time of the tannaim, but a dead language during the time of the amoraim”[1]

Now let’s decode the text a bit. To do so, we must begin with the Mishnah which precedes this Gemara. It tells how in the Temple, at the end of the first day of Sukkot, the festivities went down to the Court of Women where a great alteration had been made. This alteration, explains the Gemara, was that a gallery had been built there, so that the women could sit above and the men below, so as to avoid levity arising from contact between the sexes. But this gallery was built only after much debate. For how could it be lawful to change the Temple which had been revealed to David from on high?

That brings us to our passage above, which records the debate. The sages found scriptural sanction for the gallery by an a fortiori appeal to the segregation of the sexes in the latterday Feast of Sukkot in the last chapters of Zechariah: At Sukkot in the age to come there will be no evil inclination and the people will mourn, yet the sexes will be separated; how much more so now, when the evil inclination rules and the revelling people are prey to it.[2] The debate then turns to why the people will mourn in Zech. 12:12. (After all, they will live in the messianic age when there will be no evil, for Zech. 13:1 tells of a fountain opened to cleanse from sin.) R. Dosa says that the mourning is for Messiah ben Joseph (whose death opened the fountain which slew the evil inclination).[3] Dosa’s contemporaries disagree; they think the mourning is for the evil inclination. But the redactor dismisses their view and approves Dosa’s, citing its source, Zech 12:10. The debate makes sense throughout.

Several things emerge from the passage. First, the Talmud witnesses to belief in a Messiah descended from Joseph. Second, this Messiah ben Joseph is slain, although his slayer is unnamed. Third, Zech. 12:10 is taken as applying to him. Fourth, Zech. 12-13 is taken as implying a causal link between his slaying and the slaying of the evil yetzer. Finally, Messiah ben Joseph is not a universally accepted idea, for Dosa’s colleagues do not share his opinion. They prefer the idea that the mourning is for the demise of the evil inclination – an idea which the redactor finds irrational.

As regards the dating of the discussion, the internal evidence is substantial. The Mishnah shows the new gallery was complete when Sukkot was still fully celebrated in the Temple. The debate about its legality would therefore have taken place at least a year earlier, before the building work began. If the last year of full Sukkot celebrations was 66 CE – before Vespasian’s campaign the following spring – then the sages’ discussion must have taken place by 65 CE at the latest.

Such a date ties in perfectly with the mention of R. Dosa.[4] Safrai says that in the Mishnah and Talmud “R. Dosa” denotes the second generation tanna Dosa ben Harkinas who “is often referred to without patronymic, parallel passages showing that the Dosa referred to is Dosa ben Harkinas (cf. Eduy. 3.3 and Hul. 11.2 et al.).”[5] Dosa engaged in halakhic dispute in Temple times (Neg. 1.4) and survived until the time of Gamaliel II and Akiva, the second decade of the second century (RH 2.8-9; Yeb. 16a; y.Yeb. 1.6, 3a).[6] If we allow a generous lifespan of 85 years – from, say, 27 to 112 CE – he would have been 43 at the destruction of the Temple and might have joined in Temple debate from the age of 30. One may juggle the figures a little. But the outside dates for the debate are probably 55 to 65 CE. This agrees with the introductory rubric, Our rabbis taught (Suk. 51b), which denotes anonymous traditions from the tannaitic period or earlier.[7]

Finally, we note that Dosa and the rabbis refer to Messiah ben Joseph in a quite incidental way, as if the figure were familiar to them. As Moore says, “From the incidental way in which the Josephite Messiah and his death come in, it may be inferred that the notion was not unfamiliar.”[8] Since that is so, we must ask how old a tradition must have been for Rabbi Dosa and his contemporaries to have known it. One would assume at least that it existed in their youth, in the first half of the first century CE.

1B. KLAUSNER AND THE POST-BETHAR THEORY

Here we might rest our case, had not the passage’s dating been disputed by advocates of the view that Messiah ben Joseph arose after Bar Kokhba’s defeat at Bethar in 135 CE.[9] Surprisingly most of these commentators offer no basis for their view. We are therefore indebted to J. Klausner who does give reasons for his position.[10] He cites the second part of the text, the part beginning with the Aramaic question, “What is the cause of this mourning?” Then he comments as follows.

This passage is not a Baraitha. I strongly emphasize this point, since it has not been noticed by Castelli, Drummond, Wünsche, or Dalman. The general style of the passage, and also the Aramaic language of the introductory question, leave no doubt that we have here an Amoraic transmission of a Tannaitic interpretation.[11]

Unfortunately Professor Klausner contradicts himself from the start. After insisting that the passage is not a baraitha, he himself calls it a baraitha only two pages later.[12] Certainly his second opinion is better. For if, as Jastrow says, a baraitha is a tannaitic teaching not embodied in the Mishnah, then what is “an Amoraic transmission of a Tannaitic interpretation” if not a baraitha?[13]

But let’s get to the heart of Klausner’s argument. To make his case that the idea of Messiah ben Joseph arose after Bar Kokhba, he has to redate Dosa’s saying. He proceeds as follows. First, he cites only the last part of the text. This frees it from the obvious Temple-period dating of the foregoing section. It also cuts the Hebrew dialogue adrift in a sea of redactoral comment, allowing Klausner more easily to challenge its authority (“not a baraitha”). He then produces evidence for later Dosas.

The first issue, therefore, is whether Klausner is justified in severing the Dosa saying from the foregoing text. Is it simply the unrelated view of a later Dosa which the redactor has dropped in à propos of Zech. 12? Or is it a kindred part of the debate about Temple alterations? Surely it is plain enough. The question why the people mourn is key to Zech. 12:12, the Bible verse in hand. It was an exegetical issue that was bound to arise. Also, if the exchange between Dosa and the rabbis had been an unrelated tradition, it would have been attributed to some authority. But there is none. It is clearly part of the foregoing Temple-period exchange.

The second issue is whether any of Klausner’s other Dosas hold water. He first suggests that the Dosa of the dispute is not Dosa ben Harkinas but an otherwise unknown second-century Dosa. Citing Git. 81a, he suggests that the Dosa of that text “lived at a time much later than the school of Shammai” and, since a disciple of Shammai existed in the days of Dosa ben Harkinas’s contemporary, R. Joshua ben Hananiah (Hag. 22b), therefore Dosa ben Harkinas himself could not be said to have lived ‘much’ later than the school of Shammai. But Git. 81a does not state that Dosa lived “much later” than bet Shammai,but only that Dosa represented the teaching of the later generations and bet Shammai the earlier. As Shammai lived c.50 BCE to c.30 CE, it would be natural to describe his teaching as early compared to that of Dosa ben Harkinas who lived perhaps eighty years later. Klausner also states that Yoma 12b and BK 49a record disputes between R. Judah and R. Dosa. But Yoma 12b need not be a discussion, but simply R. Judah’s comment on Dosa’s views.[14] And BK 49a does not mention Dosa. Klausner also notes that in Zeb. 88b R. Dosa transmits a ruling in the name of R. Judah.[15] But variant readings exist for both names.[16] Therefore Klausner’s postulated existence of an otherwise unknown late second century Dosa seems unwarranted.

Klausner next suggests that the reference is to a fourth century amora, Rav Dosa.[17] As evidence, he cites the Yerushalmi parallel, y. Suk. 5.2 (23b), which, he says, describes the disputants as “two amoraim”.[18] His suggestion is immediately countered by the fact that this text, like its Bavli parallel, is a Hebrew tradition in an Aramaic frame, suggesting again a tannaitic origin. But more, Klausner’s translation ‘amoraim’ is unnatural. In the absence of any identity for the speakers, the term would be better rendered more generally, interpreters,[19] or even opinions, as follows.[20] The Aramaic passages are in italics again.

“And the land will mourn, family by family apart”(Zech. 12.12). There are two opinions. One says: this mourning is for Messiah; and the other says: this mourning is for the evil inclination.

This tradition then, like its Bavli parallel, is tannaitic, and provides no evidence for attributing Messiah ben Joseph traditions to a fourth century amora.

But the Yerushalmi passage is intriguing. There is the same Bible verse, the same Hebrew discourse in an Aramaic frame, and the same incongruous alternatives, Messiah and the Yetzer ha-ra‘. But what has become of R. Dosa? How did he become just “an interpreter”? How did “Messiah ben Joseph who was slain” become simply “Messiah”? Did the Yerushalmi redactor not know the full version of a tradition which originated in the land of Israel? Perhaps. But if he was a disciple of the ‘rabbis’ of Suk. 52a, he may have known the tradition well enough but liked it so little that he was unwilling to transmit it intact or grant it the name of the revered Rabbi Dosa.

Finally, Klausner grants that the saying in Suk. 52a might be from Dosa ben Harkinas after all, as long as he invented the idea after 135 CE. But there is no evidence at all that Ben Harkinas had such an exceptionally long life, nor do centenarians originate new doctrines in their dotage, while the disputants’ familiarity with Messiah ben Joseph belies the notion that it was a novelty.

In conclusion, Klausner does his best to make the passage originate after 135 C.E. But none of his conjectures can overturn the evidence in Suk. 52a that R. Dosa is Dosa ben Harkinas, that the debate could have made sense only while the Temple was standing, and that the text’s transmission and language are consistent with that period. I therefore suggest that Suk. 52a (top) is what it seems to be, the record of a discussion from Temple times.

2. SUK. 52A (MIDDLE): TWO MESSIAHS

Our rabbis taught: The Holy One, blessed be he, will say to Messiah ben David (May he reveal himself speedily in our days!), “Ask of me anything and I will give it to you,” as it is said, “I will tell of the decree [of the Lord],” etc. “This day I have begotten you. Ask of me and I will give you the nations for your inheritance” (Ps. 2.7-8). But when he will see that Messiah ben Joseph is slain, he will say to him, “Lord of the universe, I ask of you only life” (Ps. 21.5 [4]).

Here Messiah ben Joseph appears in the same scene as the Messiah from David. Therefore the two figures are not part of rival eschatological schemas, but part of the same drama. As in the previous passage, Messiah ben Joseph has been slain by unnamed foes. But here we learn that this event takes place before Messiah ben David receives authority over the nations. This suggests that a sequence of eschatological events is envisaged, an idea implicit in some biblical texts.[21]

As regards dating, the passage is in Hebrew, indicating an origin in the land of Israel before 200 CE. This accords with the introductory formula, Our rabbis taught, used of anonymous traditions from the tannaitic period or before.

3. SUK. 52B: THE FOUR CRAFTSMEN

“And the Lord showed me four craftsmen” (Zech. 2.3). Who are these [four craftsmen]? Rav Hana bar Bizna said in the name of Rav Shimon Hasida: ‘Messiah ben David, Messiah ben Joseph, Elijah, and the Righteous Priest.’

Our final passage gives a fuller list of the cast of the coming redemption. Messiah ben Joseph’s allies are now three – Messiah ben David, Elijah and the Righteous Priest – although the title ‘Messiah’ is borne only by himself and ben David. Each figure would presumably have a distinct role in the eschatological drama, suggesting again a sequence of events.

As regards dating, the internal evidence is slight. Little can be gleaned from language. True, the question, “Who are these [four craftsmen]?” is Aramaic while ben rather than bar suggests a Hebrew origin for the names, but such messianic patronyms might have persisted after Hebrew gave way to Aramaic in common use. Likewise the authorities quoted for the tradition – R. Shimon Hasida and R. Hana bar Bizna – show only that the tradition existed in the late second or early third century CE.[22]

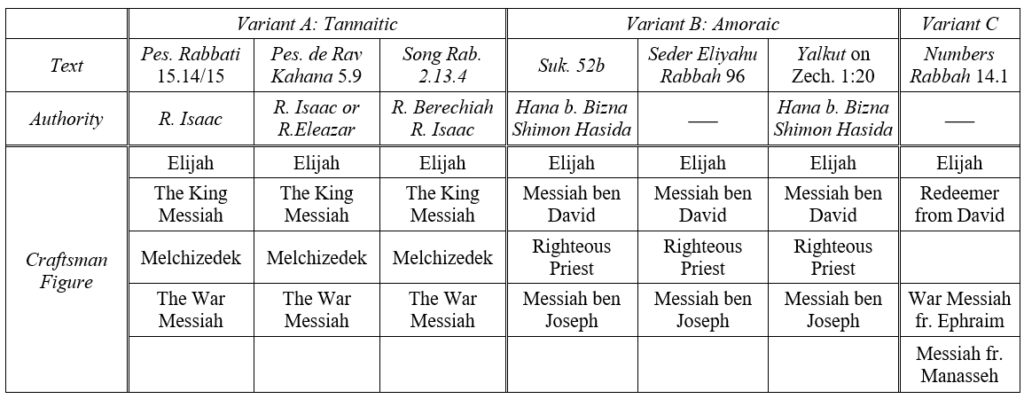

However external evidence sheds more light on dating. The ‘Four Craftsmen’ appear in a total of seven texts in two major variants. Our present text and two more give Messiah ben David, Messiah ben Joseph, Elijah and the Righteous Priest in that order.[23] As these are amoraic versions of the tradition, I shall call them Variant B. The older tannaitic version of the tradition – Variant A – also appears in three texts, which name in order Elijah, the King Messiah, Melchizedek, and the War Messiah.[24] A third variant (C) resembles B, but replaces the priest with a Manasseh Messiah.[25]

Of course, the variants A and B feature the same four figures. Elijah is the same in each version. Messiah ben David is the King Messiah. The Righteous Priest is Melchizedek – in the Bible Melchizedek is always a priest (Gen. 14:18-20; Ps. 110:4[26]) and there is supporting MS evidence.[27] That leaves Messiah ben Joseph to be identified with the War Messiah, a widely-held conclusion[28] supported by numerous texts.[29] A diagram shows the correspondence, if Variants B and C are ordered like A.

There are three key issues for dating this tradition. First, the Righteous Priest; second, the names in which the tradition is transmitted; third, the Qumran text 4Q175.

First, the Priest. The seeds of expectation of a coming priestly deliverer are found in the Bible. Ps. 110:4 features a priest-hero like Melchizedek. Zechariah presents the priest Joshua ben Jehozadak with the Davidic prince Zerubbabel as portents of things to come (Zech. 6.13). But it is in the post-biblical period that the priest-messiah comes into his own. A deliverer from Levi is prominent in the Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs.[30] Indeed, in T. Lev. 18 and T. Naph. 5.1-3 he is the foremost messiah, with no rival from the house of David. Qumran literature features a Messiah ben Aaron who will “teach righteousness at the end of days” (CD 6.11) and preside over the eschatological battle liturgy (1QM 15.4; 16.13; 18.5) and banquet (1QSa 2.12-21). A priestly messiah features in the proof-texts of 4QTest (4Q175).[31] There is the warrior-priest Melchizedek (11QMelch and probably 4Qamram and Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice) who is to judge the sons of God.[32] As in T. Levi 18, so in some Qumran literature, the priestly messiah takes precedence over the Davidic messiah (1QSa 2.14-20).[33]

The priestly Messiah therefore enjoys pre-eminence in Hasmonean times. But at the turn of the era, when Judaism and Christianity diverge, although he is taken up by Christianity and Gnosticism, particularly as Melchizedek,[34] Judaism knows him no more. The only other talmudic reference to Melchizedek, apart from this one in Suk. 52b, derogates the priesthood of the Genesis figure (Ned. 32b). Later midrashim feature the other ‘craftsmen’ – ben David, ben Joseph and Elijah – with great frequency, but have no place for the priest.[35] In Islamic times, the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Exod. 40:9-11 cites three deliverers: Elijah and the Messiahs of Judah and Ephraim; but no priest. Finally, the medieval version of the ‘Four Craftsmen’ in Numbers Rabbah 14.1 ousts the priest in favour of a parvenu Messiah from Manasseh.[36]

It therefore seems that the priestly messiah’s popularity rose with the Hasmonean dynasty who, keen to beget messianic acclaim, took Melchizedek’s title ‘Priest of El Elyon’ from Gen. 14:18.[37] But when their power was eclipsed and priestly status fell a century later with the Temple, the Priest Messiah, like his brothers, passed into obscurity, leaving only the fading flower of his former renown lingering among the ‘Four Craftsmen’.So the Righteous Priest’s presence among the ‘Four Craftsmen’ must date from a time when he was still held in honour, that is, the Temple period.

A second clue to dating the ‘Four Craftsmen’ tradition is the discrepancy in its variants. For although it is manifestly one teaching, the two main variants disagree not only in content, but also as to attribution. Variant A attributes it to the fourth generation tanna R. Isaac (fl. 140-165) according to one source, and even to the second generation tanna R. Eleazar (fl. 80-120) according to another.[38] But Variant B, as noted, attributes it to R. Hana bar Bizna in the name of R. Shimon Hasida. Now the fairly short time-gap between these teachers hardly allows for the divergence between them. The different variants therefore derive from an earlier common source. In that case, we are taken back to the period before R. Isaac – or R. Eleazar – and, once again, find ourselves near the Temple era.

Such a date is confirmed by the early first century BCE Qumran text 4Q175 (4QTest). It features four testimonies clearly demarcated by spaces and a hook-shaped symbol.[39] The first three are routinely seen as representing end-time prophet, priest and king figures.[40] The fourth figure, Joshua, on the other hand, has long been ignored. Yet, given the messianic tenor of the text, it must represent a Joshua Messiah, that is, a Messiah from Joseph. Therefore 4Q175 features prophet, priest, king, and Josephite War Messiah. These are not only the same figures as the ‘Four Craftsmen’, but are even in the same order as the tannaitic Variant A. The probability of the similarity being accidental is slight: 1 in 24, to be precise, which is the probability of four names arbitrarily falling in a given sequence. This similarity between 4Q175 and the ‘Four Craftsmen’ suggests that the Josephite Messiah was known in some form around 100 BCE.

MESSIAH BEN JOSEPH IN THE TALMUD

Messiah ben Joseph appears three times in the Talmud at B. Suk. 52. He is referred to there only as Messiah ben Joseph, in spite of references to him in the Targums as Messiah ben Ephraim,[41] or in midrashic literature as Ephraim Messiah or War Messiah.[42]

The first passage shows that he was already known in the mid-first century CE. He is slain by unnamed foes and is associated with the pierced and lamented hero of Zech. 12:10. His death effects the abrogation or ‘slaying’ of the evil yetzer. Although endorsed by Dosa ben Harkinas, he was rejected by other rabbis. The Yerushalmi parallel, Suk. 5.2, may witness to a similar aversion to Messiah ben Joseph.

The second passage dates certainly from before 200 CE. Its anonymity suggests it may be considerably older. Messiah ben Joseph is slain before Messiah ben David receives sovereignty over the nations, suggesting that a sequence of events is envisaged.

The third passage is an amoraic period tradition in which Messiah ben Joseph is accompanied by Elijah the prophet, the Righteous Priest Melchizedek and Messiah ben David. Each figure would have had a role to play, suggesting again a sequence of events. A comparison with its precursors shows that a martial Josephite Messiah was one of four expected redeemers as far back as the early first century BCE.

I therefore propose that Suk. 52 shows that Messiah ben Joseph is seen in the Talmud as part of an anticipated programme of redemption by the mid-first century CE. By that time, he already exhibited those characteristics which define him in later literature: violent death[43] with atoning power,[44] an association with Zech. 12:10,[45] and a tendency to provoke dispute.[46]

For more on this subject, see all my Messiah ben Joseph blogs. For even more, see my book Messiah ben Joseph (2016).

This article first appeared in Review of Rabbinic Judaism 8 (Brill: 2005) pp. 77-90. An updated version of it appeared in my Messiah ben Joseph (2016). For the pagination, please consult these sources.

[1] E.Y. Kutscher, “Hebrew Language, Mishnaic” EJ XVI.1590-1607: 1593. See similarly A. Sáenz-Badillos, A History of the Hebrew Language (Cambridge: University Press, 1993) 171; N.M. Waldman, The Recent Study of Hebrew (Cincinnati, Ohio: Hebrew Union College Press, 1989) 112; M. Hadas-Lebel, L’hébreu: 3000 ans d’histoire (Paris: Albin Michel, 1992) 73-74.

[2] Only Zech. 14 refers explicitly to an eschatological Sukkot (vv. 16, 19). But, as the events of Zech. 12:3-4 form an inclusio with those of 14:2-3, 12-13, and the fountain of 13:1 seems to be the source of the stream in 14:8, the aura of the eschatological autumn feast extends over the whole passage. For further details, see D.C. Mitchell, The Message of the Psalter. Sheffield Academic Press, 1997: 115-16.

[3] The events of Zech. 13:1 result from those of 12:10-14. The fountain cleanses the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem (13:1), precisely those who in 12:10-14 obtain a spirit of mercy and supplication to mourn the pierced one. The point is made by P. Lamarche (Zacharie IX-XIV. Paris: Gabalda, 1961: 85-6), who argues that Zech. 12:10-13:1 is a literary unit with the structure ABB´A´, and by W. Rudolph (Haggai, Sacharja 1-8, Sacharja 9-14, Maleachi. Gütersloh: Mohn, 1976: 227); see simlarly R. L. Smith (Micah-Malachi. Waco, TX: Word, 1984:280).

[4] As many commentators recognize. See, for instance, D. Castelli, Il Messia Secondo Gli Ebrei (Florence: Successori le Monier, 1874) 227-28; Dalman, Der leidende und der sterbende Messias der synagoge (Berlin: Reuther, 1888)3; E.G. King, The Yalkut on Zechariah (Cambridge: Deighton, Bell & Co., 1882) 107; C.C. Torrey, “The Messiah Son of Ephraim” (JBL [1947] 66:253-77) 255-73.

[5] S. Safrai, “Dosa ben Harkinas”, EJ VI.178; cf. also S. Frieman, Who’s Who in the Talmud (Northvale, NJ: Aronson) 126-127.

[6] S. Safrai, “Dosa ben Harkinas”, EJ VI.178; Frieman, Who’s Who, 127.

[7] Schiller-Szinessy notes that it is used only “of the very oldest traditions…such indeed as, by reason of their age, are unable to be traced to any known Rabbi” (cited in King, Yalkut,108). Sherira ben Hanina Gaon (906-1006), said that the formula introduces only beraitot from the bet midrash of Hiyya, the acknowledged centre for the study of tannaitic beraitot. There is no evidence that the phrase is ever used for post-tannaitic teachings (B. De Vries, “Baraitha”, EJ IV:192).

[8] G.F. Moore, Judaism II:370. Similar remarks are made by Dalman, Der leidende, 3-4; M. Buttenwieser, “Messiah” in JE VIII:505-12 (1894) 511.

[9] A. Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah (1883) 79n, 434-5; J. Klausner, The Messianic Idea in Israel (London: Allen & Unwin, 1956) 487-92; G. Vermes, Jesus the Jew (London: Fontana, 1973) 139-40. So too J. Heinemann, who suggests an existing militant Ephraim Messiah became a dying messiah by analogy with Bar Kokhba (“The Messiah of Ephraim and the Premature Exodus of the Tribe of Ephraim” in HTR 68[1975]1-15; Repr. in Messianism in the Talmudic Era [NY: Ktav, 1979: 339-353]).

[10] Klausner, Idea, 490-92. Joseph Klausner (1874-1958) held the chair of Hebrew Literature and later of Second Temple History in the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. He was a key figure in the revival of spoken Hebrew and in the establishment of the State of Israel. The nationalists favoured him as the first president of the State of Israel, in opposition to Weizmann.

[11] Klausner, Idea, 490. Klausner’s italics.

[12] Klausner, Messianic Idea, 492.

[13] Jastrow, Dictionary, 189.

[14] Despite the Soncino translation.

[15] Klausner, Idea,491.

[16] Klausner himself acknowledges that in Dikduke Sopherim the words “in the name of R. Judah” are lacking (Idea,491n). There is also a variant reading of ‘Rabbi’ for ‘R. Dosa’ (Soncino Talmud fn to Zeb 88b).

[17] Klausner, Idea,492. Presumably Klausner means the fourth century amora, Dosa ben Tebet, whose dictum on idolatry and illicit love is recorded in Song R. 7.8 (W. Bacher, “Dosa ben Tebet,” JE IV.642).

[18] Klausner, Idea, 490.

[19] See Jastrow, Lexicon,76.

[20] Dalman renders it „gibt es zwei Ansichten“ [There are two views] (Der leidende, 2n). Likewise Hengstenberg: “There are two opinions” (Christology of the Old Testament. 4 vols. [tr.] R. Keith [Washington: Morrison] II.221).

[21] See Mitchell, Message, 128-165, 199-242 for details of eschatological programmes in the Bible.

[22] R. Shimon Hasida is a little-known figure, probably of the late tannaitic period (Hag. 13b-14a; S. Frieman, Who’s Who, 291; Soncino Talmud, 722). His teachings are known mainly through his mid-third century disciple R. Hana (Frieman, Who’s Who, 84).

[23] Suk. 52b; Seder Eliyahu Rabbah 96; Yalkut on Zech 1.20 (§569).

[24] Pesikta Rabbati 15.14/15; Pesikta de Rav Kahana 5.9; Song of Songs Rabbah 2.13.4.

[25] Numbers Rabbah 14.1.

[26] This is so whether ‘al dibrati malki-tsedeq is a construct chain: You are a priest for ever according to the order of Melchizedek (LXX); or a vocative: You are a priest for ever on my account (or, according to my word) Melchizedek (cf. Job 5:8).

[27] The Munich manuscript has and Melchizedek instead of and the Righteous Priest. See R. Rabbinovicz, Variae Lectiones III (Munich: 1870) 170.

[28] G.H. Dalman, Der leidende und der sterbende Messias der synagoge (Berlin: Reuther, 1888) 6; L. Ginzberg, “Eine unbekannte jüdische Sekte” (Monatschrift für Geshichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 58 [1914]:159-77, 395-429) 421; J. Heinemann, “The Messiah of Ephraim” (HTR 68[1975]1-15) 7; H. Freedman and M. Simon, The Midrash. 10 vols. (London: Soncino, 1939). I.698n; IX.125n; Jastrow, ‘Mashiah’ in Dictionary, 852.

[29] Genesis Rabbah 99.2: “the War Messiah, who will be descended from Joseph”; Midr. Tanhuma I.103a (§11.3): “in the age to come a War Messiah is going to arise from Joseph”; Numbers Rabbah 14.1: “the War Messiah who comes from Ephraim”; Aggadat bereshit, pereq 63 (A. Jellinek, Bet ha-Midrash [BHM] IV.87. 6 vols. in 2. Leipzig: Vollrath, 1853-77; Photog. repr. Jerusalem: Wahrmann, 1967): “a War Messiah will arise from Joseph”; Kuntres Acharon §20 to Yalkut Shimoni on the Pentateuch (BHM VI:79-90, p. 81):“a War Messiah is going to arise from Joseph”; Gen. R. 75.6 applies Moses’ blessing on Joseph (Deut. 33.17) to the War Messiah.

[30] T. Reu. 6.7-12; T. Lev. 8.14; 18.1-14; T. Dan 5.10-11; T. Nap. 5.1-3; T. Jos. 19.5-9.

[31] So G. Vermes, The Dead Sea Scrolls in English (London: Penguin, 1987) 54, 295; G.J. Brooke, Exegesis at Qumran: 4QFlorilegium in its Jewish Context (Sheffield: Journal for the Study of the Old Testament) 1985: 309-10; J.J. Collins, Apocalypticism in the Dead Sea Scrolls (Routledge: London & New York, 1997) 71, 79.

[32] Vermes suggests that Qumran’s Melchizedek is entirely supernatural and non-human, and therefore cannot be a human priest-figure but should perhaps be identified with the archangel Michael (The Dead Sea Scrolls in English, 53). But human (priest) messiah figures with a heavenly origin occur not only in other texts of this period, but even in the Bible (Ps. 110:1; Dan. 7:13-14; see Mitchell, Message, 258-67, 270-71). At least one Israelite writer identifies Melchizedek with Jesus, whom he clearly regard as human (Heb. 5-7). Likewise, the way in which the versions of the ‘Four Craftsmen’ baraitha interchange ‘Melchizedek’ and the ‘Righteous Priest’ indicate that their Melchizedek is a human priestly figure. Even the talmudic tradition which states that Melchizedek was Shem ben Noah requires a human figure (Ned. 32b; Lev. R. 25.6). Presumably a human origin does not preclude being also a heavenly warrior.

[33] See J. Liver, “The Doctrine of the Two Messiahs in Sectarian Literature in the Time of the Second Commonwealth” (HTR 52 [1959]149-185; Repr. in Messianism in the Talmudic Era [NY: Ktav, 1979: 354-390]) 150-51.

[34] Christian literature: see the NT Epistle to the Hebrews (5:1-10:18), dating from late Temple times (Heb. 5:1; 7:28; 8:3-5; 9:9-10; 10:1-3, 11); Eusebius, History, I.3. For Gnostic literature, see the Melchizedek Tractate from Nag Hammadi (NHC IX, 1). For more details, see J.R. Davila, “Melchizedek, the ‘Youth,’ and Jesus,” in The Dead Sea Scrolls as Background to Postbiblical Judaism and Early Christianity (ed. James R. Davila; STDJ 46; Leiden: Brill, 2003) 248-74.

[35] In the apocalyptic midrashim referring to Messiah ben Joseph or his pseudonyms, ben David and Elijah appear in (1) Aggadat Mashiah in BHM III.141-43; Mitchell, The Message of the Psalter,304-7 (ET); 335-36 (Heb.); Buber, Leqah Tob (Jerusalem, 1959; 1st ed. Vilnius: 1880) II.258-9; Horowitz, Beth ‘Eqed Agadoth (1881) 56-58; (2) Otot ha-Mashiah in BHM II.58-63; Mitchell, Message, 308-14 (ET); 336-40 (Heb.); (3) Sefer Zerubbabel in BHM II.54-57; Mitchell, Message, 314-20 (ET); 340-43 (Heb.); (4) ‘Asereth Melakhim in Eisenstein 1915: II.461-66; Mitchell, Message, 320-22 (ET) 343-44 (Heb.); (5) Pirqe Mashiah in BHM III.70-74; Mitchell, Message, 322-29 (ET); 344-47 (Heb.); (6) Saadia Gaon, Kitab ’al-’Amanat wal-I‘tiqadat §VIII.5-6 (editio princeps, p.238-237); (7) Tefillat Rav Shim‘on ben Yohai in BHM IV.117-26; (8) Pereq Rav Yo’shiyyahu in BHM VI.112-116; esp. p.115. Ben David appears with ben Joseph but not Elijah in (9) Nistarot Rav Shimon ben Yohai in BHM III.78-82; Mitchell, Message, 329-34 (ET); 347-50 (Heb.); (10) Midrash Wayyosha 15.18 in BHM I.35-57.

[36] Numbers [Bammidbar] Rabbah 14.1 was compiled in the mid-12th (M. D. Herr, ‘Numbers Rabbah’, EJ 12:1261-63) or early 13th (G. Stemberger, Einleitung in Talmud und Midrasch [8th ed., Munich, Beck]305-306) century, from considerably older material (Herr, ibid.).

[37] See Josephus, Ant. 16.6.2; RH 18b; the anti-Hasmonean Ass. Mos. 6.1. See too the levitical “prophet of the Most High” at T. Levi 8.14.

[38] The Braude and Buber (51a.§16) editions of Pes. de Rav Kah. attribute it to R. Isaac, but Wünsche’s German translation testifies to ‘R. Eleasar’ (Bibliotheca Rabbinica. 3 vols [Leipzig: Schulze, 1885] 2.61). Shir R. 2.13.4 attributes it to R. Berechiah in the name of R. Isaac. Pes. R. 15:14-15 attributes it simply to R. Isaac. Without patronymic, R. Isaac refers to the fourth generation Babylonian-born tanna who moved to the land of Israel and was a contemporary of Shimon b. Yohai and Judah ha-Nasi (Gen. R. 35:3; Ber. 48b; Git. 27b; Soncino Talmud, 659; Frieman, Who’s Who, 375). R. Eleazar, without patronymic, refers to Eleazar b. Azariah the nasi, who lived c. 50-120 ce. (Meg. 26a; Z. Kaplan, “Eleazar b. Azariah” in EJ VI:586-87; Soncino Talmud, 640). R. Berechiah probably indicates the fourth century amora,Berechiah ha-kohen, but some scholars recognize a third century amora,Berechiah Sabba (EJ IV:596; Frieman, Who’s Who, 72).

[39] For details, see F.M. Cross, “Testimonia (4Q175=4Qtestimonia=4Qtestim)” 6B:308-11 in J.H. Charlesworth (ed.), The Dead Sea Scrolls. 6 vols(Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2002) 6B:308.

[40] So G. Vermes, Jesus the Jew, 96; The Dead Sea Scrolls in English,54, 295; G.J. Brooke, Exegesis at Qumran: 4QFlorilegium in its Jewish Context (JSOTSS 29; Sheffield: JSOT, 1985) 309-10; F. García Martínez, Qumran and Apocalyptic (Leiden: Brill, 1992) 174; F. García Martínez & J. Trebolle Barrera, The People of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Leiden: Brill, 1995) 186; J.J. Collins, Apocalypticism in the Dead Sea Scrolls (Routledge: London & New York, 1997) 71, 79.

[41] For Ben Ephraim, see Tg Tos. to Zech 12:10; Tg on Song of Songs 4.5; 7.4; Tg Ps.-J. on Exod. 40:9-11. See too Mid. Teh. 60.3; 87.6; NRSY 22-26; Zohar Mishpatim, 477-78; Beha‘alotcha, 92; Pinhas, 565-582.

[42] For Ephraim Messiah, see Pes. R. 34, 36-37; Midrash Aleph Beth 11b.15. For War Messiah, see Gen. R. 75.6; 99.2; Midr. Tan. §11.3 (I.103a); Pes.R. 8.4 and 15.14/15; Pes. K. 5.9; Song R. 2.13.4; Num. R. 14.1; Aggadat bereshit, pereq 63 (BHM IV.87).

[43] See also Tg. Tos. to Zech 12.10; Ag. M. 27; Otot 7.12; PRE 22a.ii; Sef. Z. 40; As. M. 4.14; Pir. M .5.45(King Nehemiah the Messiah, a pseudonym for Messiah ben Joseph); Mid. Way. 18; NRSY 25-26; TRSY (Nehemiah ben Hushiel; the pseudonym again); Sa’adia, Kitab 8.5 (tr. S. Rosenblatt, The Book of Beliefs and Opinions. Yale University Press, 1948: 301-302); Rashi on b. Suk. 52a; Ibn Ezra on Zech. 12.10; Zohar (ed. Ashlag; Jerusalem, 1945); Shlach Lecha, 174; Balak, 342; Ki Tetze, 62; Abravanel on Zech 12.10; Alshekh, Marot ha-Zov’ot on Zech 12.10. Pes. R. 36.1 refers to Ephraim Messiah’s great suffering rather than his death, but applies to him Ps. 22.16[15], whose sufferer is laid in the dust of death. PRS describes the resurrection of Nehemiah ben Hushiel, which implies his death.

[44] Pes. Rabbati 36-37; Saadia Gaon, Kitab al Amanat VIII.6 (Rosenblatt, The Book of Beliefs, 304); Alshekh, Marot ha-Zove’ot on Zech. 12.10; R. Naphtali ben Asher Altschuler, Ayyalah Sheluhah (Cracow, 1593)on Isa. 53.4.

[45] Tg Tos. to Zech 12.10; Aser. Mel. 4.14; Midr. Way. 18.15 (BHM 1.56); NRSY 25; Saadia, Kitab 8.5 (Rosenblatt, The Book of Beliefs, 301-302); Rashi on Zech 12.10 and Suk. 52a; Ibn Ezra on Zech. 12.10; Kimchi on Zech. 12.10; Abravanel on Zech. 12.10; Alshekh Marot ha-Zove’ot on Zech. 12.10. References to Zech. 12.12: y. Suk 5.2; Ag. M. 2.27. Rashi and Kimchi both dispute the validity of the Messiah ben Joseph interpretation at their commentary on Zech 12.10; Rashi, however, appears to affirm it at his comment on Suk. 52a.

[46] This is perhaps best seen from attempts to displace Messiah ben Joseph. R.P. Gordon suggests that the reference to Ben Joseph in Tg Tos. to Zech. 12:10 was originally the standard Targum, but was edited out (K.J. Cathcart and R.P. Gordon, The Targum of the Minor Prophets. The Aramaic Bible 14; Wilmington, Delaware: Michael Glazier, 1989. 220 n.2). Likewise the Venice MS of Pirqê de Rabbi Eliezer 22a.ii shows signs of Ben Joseph having been edited out (see Mitchell, The Message, 269 n.). Even Kimhi disputes the traditional reference to Ben Joseph at his commentary on Zech. 12:10.