Two mysterious bull figures, a firstborn shor and a rem, feature in 1 Enoch 90 and in Deuteronomy 33. All agree that the figures in 1 Enoch speak of the Messiah. But what about those in Deuteronomy? Could they be about the Messiah too? Here I argue that they are. In fact, they speak about a Josephite Messiah, that is, a Messiah ben Joseph.

The Animal Apocalypse of 1 Enoch, dating from about 165 bce, is a theriomorphic depiction of the messianic age.[1] The central figures are a white bull and its successor, a mysterious entity called in Ethiopic nagar, that is, ‘thing’ or ‘word’. Commentators agree that the white bull represents the Messiah.[2] But what of the nagar? Some sixty years ago C.C. Torrey suggested that it represents Messiah ben Joseph,[3] the mysterious slain Messiah of rabbinic literature.[4] At the time his view was largely dismissed.[5] However, since it seems to me that Torrey was looking in the right general direction, even if he did not quite secure his arguments, and since no satisfactory hypothesis for the passage’s unique symbolism has yet been proposed, it is perhaps time to revisit the proposal that this text features a Josephite Messiah.

Therefore by a comparison of 1 En. 90.37-38 with what I shall propose is its source text, Deut. 33.17, I hope in this paper to confirm Torrey’s view that the nagar represents a Josephite Messiah. I hope also, contra Torrey, to show that both the white bull and the nagar represent the Joseph Messiah in two different manifestations or avatars, one sacrificial, the other sovereign. Finally I hope to show that the Josephite Messiah was not a later idea read into Deut. 33.17, but a necessary deduction from it from earliest times.[6]

1. 1 ENOCH 90.37-38

Although sections of the Enoch compendium have been found in both Aramaic and Greek, with parts of the Animal Apocalypse in Greek alone, vv. 37-38 are found only in the Ethiopic, a text showing signs of corruption. There are therefore interpretational issues to address before we proceed, particularly in v. 38, which is as follows.

I saw till all their generations were transformed, and they all were-became white bulls; and the first among them was-became a nagar; the nagar was-became a great beast and had great black horns on its head.

The issues are two. First, who becomes what? Second, what is the nagar?

1A. WHO BECOMES WHAT?

The question of who is transformed into what hinges on the Ethiopic verb ‘to be’ (kôna) which can be rendered either was or became. It occurs three times.

(a) They all were-became white bulls. Here the verb should clearly be taken as became rather than was, for the issue is the transformation of the beasts and birds of v. 37 into bulls. No other understanding is really possible, nor, to my knowledge, has it been proposed.

(b) The first among them was-became a nagar. This is harder. Does the first bull become a nagar? Or is the nagar a new unrelated figure who appears at this point as ‘first’ or chief among the white bulls?[7]

The majority of commentators endorse the first option.[8] Rightly so. For if the nagar is a completely new creature who appears at this point, then the white bull simply drops from the narrative after one verse. This would be surprising, given the detailed description of him and his importance among the animals. But if the nagar is the white bull transformed, it is consistent with the earlier transformation of the beasts and birds into white bulls. The lesser become great, the great become greater, in line with such descriptions of the messianic age as Zech. 12.8.

Here I diverge from Torrey who felt that ‘the Lord of the sheep rejoiced over them and over all the oxen’ (v. 38) is compelling evidence for two separate oxen, the first representing Messiah ben David, the second Messiah ben Joseph.[9] The phrase may mean simply that the Lord of the sheep rejoiced over all his creatures. Or that he rejoiced over his sheep as well as the oxen (v. 34). For it is not said that the sheep become bulls; and even if they do, he would rejoice in his transformed flock being no longer prey (cf. 1 En. 89). Or again, them may indicate the nagar and the sheep, or even two manifestations of the one Messiah.

Whichever way, Torrey’s objection is not sustained on textual grounds. In addition, there are two serious objections to the white bull representing Messiah ben David. First, Ben David never precedes Ben Joseph in Israelite tradition. The principle is always ‘he [Joseph] came first in Egypt and he will come first in the age to come’.[10] Second, it is unlikely that Ben David would be symbolized by an ox; his symbols are always the lion or ass.[11]

(c) The nagar was-became a great beast and had great black horns on its head. Is the nagar a great horned beast? Or alternatively, does it become a great horned beast?

Once again the majority of commentators endorse the first option, seeing the second phrase as a description of the nagar.[12] Again rightly so. For if the nagar is transformed into a great horned beast, then the nagar itself would be an incomprehensible bird of passage, appearing for a trice, a ‘thing’ nameless, functionless, formless, an unexplained pupa of the white bull’s frenetic metamorphoses into a great horned beast. And in that case, the great horned beast is itself nameless and unspecified.

This would be surprising, for all other animals in the apocalypse are named by species (1 En. 85–90): bulls, elephants, camels, asses, lions, tigers, wolves, dogs, hyenas, wild boars, foxes, squirrels, swine, falcons, vultures, kites, eagles, and ravens; even ‘birds of the air’ and ‘beasts of the field’ are species in light of biblical usage. But ‘great beast with great black horns on its head’ is a vague description of what is clearly an important figure in the narrative. However all makes sense if the nagar is itself the great horned beast. In that case, the Ethiopic translator wants to explain what the nagar is, and so he provided a gloss.This leads to our next point.

1B. WHAT IS THE NAGAR?

The Ethiopic term nagar, as noted above,generally signifies ‘thing, word, deed’. However such a reading is hardly satisfactory, being inconsistent with the theriomorphism of the passage. The Ethiopic translator recognized this. For he brought the nagar back to the theriomorphic realm by telling us that it is a great beast with great black horns on its head. Such a beast then is the nagar. Now which beast could this be? An answer is found both in the likely derivation of the term nagar and in a process of zoological sleuthery. Let us start with the latter.

We seek a great beast with great black horns on its head. Although one might think that many beasts could fit such a description, in practice this is not so. For a start, most animals have grey-white medium-sized horns. Then buffalo and ram have horns beside, not on,their head; the rhinoceros does not have horns on its head; the extinct wisent or European bison had small horns; and the unicorn has only one horn. As for goat, ram and gazelle, they are not ‘great beasts’. If we make less of the horns being on the head, and accept side-projecting rising horns, then a large domestic bull, bos taurus, with abnormally dark and large horns, might be a passable candidate. But our Ethiopic translator already had a word for that animal—he had just mentioned it in the same verse—and clearly intended another beast.

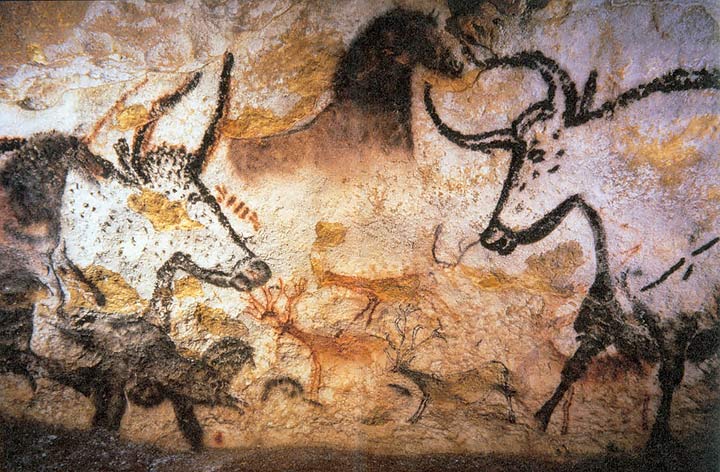

In fact, in all zoology there is only one animal which fits the description. It is the extinct wild ox or aurochs, bos primogenius, a large long-horned ox formerly inhabiting North Africa, Europe and South-West Asia.[13] The aurochs was famed for its size and its great black horns which rose straight up from its head. Its Hebrew name, rem, deriving from r’m, suggests its great size.

Rabbinic tales dwell on the aurochs. One tells how the aurochs did not enter the ark, but only its offspring, for it was too large; another tells how King David found an aurochs asleep in the desert and, thinking it a hill, climbed upon it, and being then borne away, promised to build a temple a hundred cubits high—like its horns—in return for his safety; again, we are told that its horns are larger than all beasts’ and it is called rem because its horns are ram.[14] None of the rem’s competitors match these attributes or fit the Ethiopic translator’s description half as neatly.

The conclusion that the nagar is the aurochs is supported by Dillman’s ‘excellent conjecture’.[15] He suggested that the Ethiopic translator was working from a Greek text which had been translated from an Aramaic original. The Aramaic word for aurochs, rēma, had been simply transliterated into Greek, resulting in ρημα, Greek for ‘word’. Seeing this in his Greek text, the Ethiopic translator gave his equivalent term, nagar. Then, knowing what animal was intended, he provided a description. Dillman’s view has since been confirmed by Qumran evidence for an Aramaic original of the Apocalypse.[16]

Here Lindars objected that ‘there seems no strong reason why the Greek translators should resort to transliteration at this point’.[17] But there is in fact a very good reason why they should have done so. If the Greek translator had no word for the aurochs in his own language, he would have no option but to transliterate. This seems likely, as the Septuagint consistently translates Hebrew rem as monokerōs, ‘unicorn’.[18] As for why the Ethiopic translator did not correct the mistake that is also simple. He too had no word for the aurochs which did not inhabit Ethiopia.

So we conclude with the widely-accepted view that the nagar is an aurochs.[19] We may now render the passage as follows.

37. And I saw that a white bull was born, with large horns, and all the beasts of the field and all the birds of the air feared him and made petition to him all the time. 38. I saw till all their generations were transformed, and they all became white bulls; and the first among them became an aurochs (the aurochs was a great beast and had great black horns on its head); then the Lord of the sheep rejoiced over them and over all the oxen.

On this basis we can now decode the imagery of 1 En. 90.37-38 as follows. The Messiah, symbolized by a white bull, is born. Thereafter the nations, beasts and birds, are transformed into his likeness. Then the Messiah is transformed into a more splendid state, represented by an aurochs. Then all dwell together in the favour of God.

2. DEUTERONOMY 33.17

Only one biblical verse features bos taurus and bos primogenius together. That is Deut. 33.17, the end of Moses’ blessing on Joseph and his tribes (vv. 13-17). From here on I shall refer to these animals by the Hebrew terms shor and rem to avoid the ambiguities inherent in English.[20] Here are vv. 16-17.

Let it [the blessing] come upon the head of Joseph, and upon the crown of the prince among his brothers.

The firstborn of his shor, majesty is his; and the horns of a rem are his horns. With them he shall gore the peoples, all as one, even to the ends of the earth.

Such are the ten thousands of Ephraim; such are the thousands of Manasseh.

There are two issues to address here. First, what does the shor and rem imagery represent? Second, to whom does it apply?

2A. IMAGERY

Although the shor and the rem are both oxen, they are very different beasts. The shor is a slave. A bearer of burdens, a puller of loads, it lives captive among human dwellings, its great strength bent to servitude; it is milked, slaughtered, and turned to beef and hide. Above all, in Israel, where every firstborn male belonged to Yhwh who smote the firstborn of Egypt, the phrase ‘firstborn of a shor’ denotes an animal destined to violent sacrificial death.[21] All Israelites living within the sphere of the cult would have known to their cost the implications of this phrase. The connection is made, for instance, at Est. R. 7.11.

In [the Zodiacal sign of] Taurus was found the merit of Joseph who was called ox, as it says, The firstborn of his shor, majesty is his (Deut. 33.17); and also the merit of the offering, as it says, A bull [shor], or a sheep, or a goat when it is born [shall be seven days with its mother; and from the eighth day on it shall be accepted as an offering made to Yhwh by fire (Lev. 22.27)].

The rem, on the other hand, is not a servant but a king. A majestic wild beast, it roams unyoked in virgin forest and steppe, its proverbial ferocity inspiring fear and awe among beholders (Num. 23.22; Job 39.9-12).[22] It has no fear of being delivered up as a sacrifice. Not only would none dare meddle with it, but it had no place as a sacrifice in Israel’s cult (Lev. 1.2).

There is then a total contrast between the firstborn of a shor and a rem. Oneis servile, burdened, despised, and destined to sacrificial death; the other, sovereign, free, revered, and destined to life. Lest I be suspected of reading too much into two beasts, the same contrast is noted at Gen. R. 39.11.

There were four whose coinage became current in the world:

(i) Abraham, as it is said, And I will make of you, etc (Gen. 12.2). And what effigy did his coinage bear? An old man and an old woman on one side, and a youth and a maiden on the other.

(ii) Joshua, as it is said, So the Lord was with Joshua and his fame was in all the land (Josh. 6.27), which means that his coinage was current in the world. And what was its effigy? A shor on one side and a rem on the other, corresponding to The firstborn of his shor, majesty is his; and the horns of a rem are his horns (Deut. 33.17).

(iii) David, as it is said, And the fame of David went out into all the lands (1 Chr. 14.17), which means that his coinage was current. And what was its effigy? A [shepherd’s] staff and bag on one side, and a tower on the other, corresponding to Your neck is like the tower of David, built with turrets (Song 4.4).

(iv) Mordecai, as it is said, For Mordecai was great in the king’s house, and his fame went forth throughout all the provinces (Est. 9.4); this too means that his coinage was current. And what was its effigy? Sackcloth and ashes on one side and a golden crown on the other (cf. Est. 4.1; 8.15).

In each case the two sides of the coin present contrasting states of affliction and exaltation. David is raised from shepherd to royal builder of fortifications. Mordecai is lifted from the ashheap to power and dignity. Abraham is elevated from the disgrace of childless old age to the blessing of married progeny—Isaac and Rebekah—and a future. By implication Joshua’s shor and rem represent contrasting states of lowliness and exaltation.

Finally the shor and the rem of Deut. 33.17 are one. This is seen principally from their symbolizing one entity, namely Joseph (Deut. 33.13-16) as the representative head of his tribes (v. 17). But it is seen also from the shor’s ‘majesty’ which befits him to possess the rem’s fearsome horns, its corona.[23] And with such horns, such a crown, the shor becomes the rem.

That a transformation of shor to rem is envisaged is seen from the options. For if the two were simultaneously one, it would be a hybrid without the distinctive characteristics of either. That would make nonsense of the imagery. If however the rem were to become a shor, in defiance of their order of appearance in the text, they would depict a hero who briefly triumphs and is then consigned to humiliation. That would be a mediocre fate altogether compared to the suggested alternative, ascent from humiliation to lasting triumph, if the shor becomes the rem.

But how does the shor become the rem? How does a creature destined to sacrifice become triumphant? Clearly not by avoiding its destiny. Its way to resurgence and transformation must be in some way through sacrifice and death.

2B. REFERENT

The oxen of Deut. 33.17 are then one entity in two contrasting states of lowliness and exaltation. But whom do they represent? Three possibilities exist.

JOSEPH

First, being part of the blessing on Joseph, they represent Joseph and his tribes. In fact, on the basis of this text, the ox—firstborn, domestic, rem,or generic—and its horns become in Israelite literature the proper symbol of the Josephites for ever.

The Ephraimite military have a punning brag about acquiring by their strength horns for themselves in reconquering the Transjordanian town of Karnaim (Amos 6.13). In their sword-songs they sport iron horns to gore (ngḥ) the nations, a clear allusion to Deut. 33.17 (1 Kgs 22.11; 2 Chron. 18.10). In Ps. 22.22 (21) the horns of the wild oxen and the mouth of the lion surely represent Ephraim and Judah—signifying by merismus all Israel—united under Saul against David. In Ps. 29.6 Mt Hermon-Sirion on the northern horizon of the Kingdom of Ephraim is likened to a frisky young rem.

The identification continues in post-biblical literature. In the Testament of Naphtali 5.6-7, Joseph seizes a great black bull with two great horns and eagle’s wings and ascends into the heavens. In Numbers Rabbah the camp of Ephraim are said to have marched through the Sinai under a banner adorned with a bull-emblem (2.7; cf. 2.18). Elsewhere in rabbinic literature, as we shall see below, there are scores of instances where the oxen of Deut. 33.17 represent Joseph or his descendants.

Such symbolism surely befits Joseph, the blameless youth compelled into servitude and delivered to the virtual death of pit and dungeon (Gen. 37.24; 39.20), but later raised to sovereignty, freedom and life (Gen. 41.39-45).[24] Like the sacrificial victim, his affliction ultimately gave life to Israel (Gen. 50.20). Joseph being then the exalted rem, his horns would represent his vigorous offspring, Ephraim and Manasseh. The verse is routinely applied to Joseph in rabbinic literature.[25]

JOSHUA

However a second interpretation is possible. One can see in the ‘firstborn’ a reference to a descendant of Joseph through Ephraim. The term firstborn has a particular resonance with Ephraim who, though not a natural firstborn, obtained, like three generations of his progenitors, titular primogeniture.[26] And if, on the basis of v. 16, the first his pronoun of v. 17 refers to Joseph, then the firstborn of his shor would be some generations down from Joseph—Joseph, his shor, its firstborn—and would represent a hero to arise from Joseph through Ephraim.[27]

The obvious candidate for the reference is Joshua. He too, like Joseph, knew both lowliness and exaltation. According to E.G. Hirsch, in rabbinic literature ‘Joshua is regarded as the type of the faithful, humble, deserving, wise man’.[28] Though an Ephraimite prince, he did not rebel in the desert, as did others. Instead he humbly served Moses until he was eventually appointed commander of Israel in preference even to Moses’ own sons.[29] Like Joseph, his voluntary humiliation was ultimately life-giving, delivering Israel from the desert and bringing them into the Promised Land. The horns of the aurochs would again represent the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh who followed him and gored the nations of Canaan. Rabbinic literature frequently refers Deut. 33.17 to Joshua also.[30]

MESSIAH BEN JOSEPH

Finally the passage can be taken as referring to a future descendant of Joseph and Joshua. In fact, as Strack and Billerbeck note, such an idea was bound to be inferred from Joshua’s merely partial fulfilment of the words of the blessing.[31] For Joshua did not gore the peoples, all as one, to the ends of the earth, but only the seven nations of Canaan. The discrepancy between prediction and event would have led naturally to the conception of a future Joshua who would fulfil the prophecy entirely.

Such a figure, known in rabbinic literature as Messiah ben Joseph or ben Ephraim,[32] is frequently associated with Deut. 33.17.[33] Like Joshua he stands at the head of Ephraim and Manasseh to fight the wars of the Lord.[34] Like Joseph and Joshua he is raised from sacrificial humiliation to triumph, dying for the sins of Israel[35] and being raised to honour in the messianic kingdom.[36]

At this stage we therefore reach an important conclusion. A coming Josephite hero, a Messiah ben Joseph, rather than being a a later idea read into Deut. 33.17, appears to be implicit in it. There are three reasons why this is so. (1) The text speaks clearly of a Josephite hero, one perhaps like Joshua (referred to either prospectively or retrospectively depending on one’s view of dating). (2) The imagery of the firstborn shor and rem shows that he must suffer sacrificially before being exalted. (3) Since Joshua did not fulfil the conquest of all nations, nor was it even his remit (Josh. 3.10), this hero was bound to be looked for in the future.

3. A SACRIFICIAL JOSEPHITE MESSIAH IN 1 ENOCH 90.37-38

There is therefore a clear resemblance between 1 En. 90.37-38 and Deut. 33.17. Both are theriomorphic representations of hero-figures; both feature the same two bovids in the same order. This can hardly be coincidental. Rather Deut. 33.17 seems to be the source-text for the imagery of 1 En. 90.37-38. We are therefore justified in appealing to the former to interpret the latter.

In the light of Deut. 33.17 it seems like 1 Enoch’s messianic white bull represents a messianic figure, or Messiah, from Joseph-Joshua. This is not simply because of the symbol of the bull or ox, but because it changes into a rem, like the hero of Deut. 33.17. Moreover, as in Deut. 33.17, he seems to be a firstborn bull. For it is his birth which brings about the transformation of the wild creatures into his likeness, and he is called the ‘first’ among the white bulls so transformed (v. 37).[37]

This white bull also represents a sacrificial messianic figure. For the bull was a sacrificial animal, especially the firstborn bull, which was inevitably destined to sacrificial death. The bull of 1 En. 90.37 is a perfect sacrifice. His whiteness represents his ethical perfection (cf. Isa. 1.18; Ps. 51.9 [7]).[38] After his suffering and death he will be transformed into a majestic state, represented by the aurochs.

Therefore 1 En. 90.37-38 can be interpreted as follows. The Messiah is born. His representation as an ox shows his lineage from Joseph, Ephraim and Joshua; his whiteness shows his faultless rectitude; and his great horns represent his majesty and power; the homage of the beasts and birds represents his acclamation among the nations. This unblemished creature is destined, like every firstborn male ox in Israel, to die as a sacrifice. The death is not described, but its results are.

The first result is that the human race is transformed into white bulls in line with the Messiah’s image. Here the writer has moved beyond Deut. 33.17 and seems to be drawing on texts such as Isa. 53.11. The second result is that the Messiah himself is transformed—as with the shor of Deut. 33.17 and innocent Joseph—from his former servile state into a new one of sovereignty and power. This surely implies his return from death to life—whether by reincarnation, resurrection, or some other reappearance—as surely as the firstborn bull was destined to die. Then the exalted Messiah and all redeemed humankind live in the favour of the Lord of the Sheep, the God of Israel.

4. FINAL OBSERVATIONS

We are now in a position to respond to some final objections. Lindars remarked, ‘Why should the Messiah change from being a domestic animal into a wild animal of the same species?’[39] The answer is now clear. Since both these animals are a biblical symbol for a hero from Joseph-Ephraim, the writer chose them to represent just such a figure. If it be objected that bulls represent the line from Adam to Isaac throughout the Apocalypse (85.3–89.12), one may respond that they are not altogether the same; unlike the Messiah, the patriarchs do not become aurochsen. But insofar as they are all white bulls, the writer may wish to suggest that the patriarchs, like the messianic figure, were patient bearers of the yoke of Torah; and that the Messiah, like the patriarchs, is the head of a new race, not simply a continuation of Israel, the sheep.

Rowley objected to Torrey’s identification of the nagar with Messiah ben Joseph-Ephraim as follows.

The fact that this [1 En. 90.38] is generally regarded as an allusion to Deut. 33.16f., and that later speculation interpreted that Biblical passage of the warrior Messiah, is not very clear evidence that the writer of 1 Enoch was thinking of the Messiah ben Ephraim.[40]

Rowley’s inability to see Messiah ben Ephraim in 1 En. 90.38 is surely due to his failure in reading Deut. 33.17. If it is an allusion to Deut. 33.16-17, as he allows, then it cannot refer to anyone other than a coming Josephite deliverer for the reasons given above. Such a figure may justly be called Messiah ben Ephraim. Likewise Rowley’s failure to connect Messiah ben Ephraim with the War Messiah or mashuah milhamah appears to be due to his lack of awareness of rabbinic traditions on the subject, which repeatedly identify Messiah ben Joseph-Ephraim with this very figure.[41] The same shortcoming is unfortunately evident in his other remarks on Messiah ben Joseph.[42]

5. FIRSTBORN SHOR AND REM IN 1 ENOCH 90 AND DEUTERONOMY 33:17.

I have reasoned as follows. (1) In 1 En. 90.37-38 the messianic white bull becomes an aurochs. (2) The same transformation appears in Deut. 33.17; there the two oxen represent sacrificial and triumphant aspects of a coming Joseph-Joshua hero. (3) The unique coincidence of imagery in these two passages strongly suggests that 1 En. 90.37-38 is dependent on Deut. 33.17. (4) Conclusion: The white bull of 1 En. 90.37-38 depicts an anticipated Joseph-Joshua Messiah destined to sacrificial death, and the nagar-rem represents his post-mortem resurgence in sovereignty and power.

There can be no ground for objection to such a conclusion per se, since a dying and resurrected Joseph-Joshua Messiah is a familiar figure in rabbinic literature.[43] The only objection can be to the dating of the idea, for it has long been maintained that the idea of the suffering Josephite Messiah dates from long after the Animal Apocalypse.[44]

THE DATE OF MESSIAH BEN JOSEPH

1 Enoch 90.37-38 therefore has implications for the dating of the Josephite Messiah. It adds its witness to the case for the idea existing in all essentials centuries before the first rabbinic references.[45] Indeed, the idea and its symbolism must have been already well established when the Animal Apocalypse appeared for its theriomorphic code to have been comprehensible.

INTERPRETATION OF DEUT. 33.17

It has implications in turn for the history of interpretation of Deut. 33.17. Its Josephite ox-hero who will subdue all nations must have elicited early speculation about an eschatological suffering and rising Joshua. This may in fact be the true source of the Messiah ben Joseph idea.[46]

OTHER SECOND CENTURY BCE TEXTS

It has implications for the authenticity of other second century BCE texts which are regarded on ideological grounds as Christian interpolations. One thinks particularly of T. Benj. 3.8, whose spotless Josephite Lamb of God shall die for the ungodly, and of Sib. Or. 5.256-59 whose sun-stopping (Joshua) pre-eminent man shall come again from heaven to where he spread on the fruitful wood his hands.[47]

AND CHRISTIAN ORIGINS

Finally, there are implications for Christian origins. Perhaps the New Testament writers were not the first Israelites to believe that a second Joshua ben Joseph would die as a sacrifice for the transformation of mankind and then rise to power.

For more on this subject, see all my Messiah ben Joseph blogs. For even more, see the book Messiah ben Joseph (2016).

This blog first appeared in Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 15.3 (2006) pp. 211-28. You can get the text on the Scholarly articles page.

[1]. E. Isaac dates the Animal Apocalypse from 165 bce or earlier (‘1 Enoch’, in OTP, I, pp. 5-89 [7]). P.A. Tiller (A Commentary on the Animal Apocalypse of 1 Enoch [Atlanta: Scholars, 1993], pp. 78-79) dates it shortly after 165 and J.T. Milik to 164 bce (The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments of Qumrân Cave 4 [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976], pp. 44, 244). Such a date is consistent with the Qumran fragment 4QEnf of the Apocalypse dating from 150–125 bce (Milik, Books of Enoch, pp. 41, 244-45).

[2]. A. Dillmann, Das Buch Henoch (Leipzig: Vogel, 1853), p. 286; M. Buttenwieser (‘Messiah’ in JE,VIII, pp. 505-12 [509]); R.H. Charles, The Book of Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1893), p. 258 n. 1; F. Martin, Le Livre d’Hénoch (Paris: Letouzey et Ané, 1906), p. 235n; Isaac, ‘1 Enoch’, p. 5; C.C. Torrey, The Apocryphal Literature (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1945), p. 112; ‘The Messiah Son of Ephraim’, JBL 66 (1947), pp. 253-77 (266); B. Lindars, ‘A Bull, a Lamb and a Word: I Enoch xc.38’, NTS 22 (1976), pp. 483-86 (485). Milik, Books of Enoch, p. 45, and Tiller, Commentary, p. 388, prefer the term ‘eschatological patriarch’ or ‘second Adam’, the latter noting also his universal dominion (Tiller, Commentary, p. 385). As far as I am aware the passage has not yet been covered in the University of Michigan’s Enoch Seminars.

[3]. C.C. Torrey, ‘The Messiah Son of Ephraim’, JBL 66 (1947), pp. 253-77 (267).

[4]. There are references to Messiah ben Joseph in rabbinic literature of all periods and genres. Among the older texts, see Suk. 52a; Tg. Tos. to Zech. 12.10; among midrashic literature see my translations of Aggadat Mashiah, Otot ha-Mashiah, Sefer Zerubbabel, Asereth Melakhim, Pirqei Mashiah, and Nistarot Rav Shimon ben Yohai ,in D.C. Mitchell, The Message of the Psalter (JSOTSup, 252; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997), pp. 304-50. I have also cited the Messiah ben Joseph traditions from the Midrash on Psalms in the third section of my article ‘Les psaumes dans le Judaïsme rabbinique’, RTL 36.2 (2005), pp. 166-91.

For discussion of the content and dating of these traditions, see my articles ‘Rabbi Dosa and the Rabbis Differ: Messiah ben Joseph in the Babylonian Talmud’, Review of Rabbinic Judaism 8 (2005), pp. 77-90; ‘The Fourth Deliverer: A Josephite Messiah in 4QTestimonia’, Biblica 86.4 (2005), pp. 545-53; ‘Messiah bar Ephraim in the Targums’, Aramaic Studies 4.2 (July 2006). An older classic work on the subject is G.H. Dalman, Der leidende und der sterbende Messias der synagoge im ersten nachchristlichen Jahrtausend (Berlin: Reuther, 1888).

[5]. See particularly H.H. Rowley’s influential article, ‘Suffering Servant and Davidic Messiah’, in his The Servant of the Lord and Other Essays on the Old Testament (Oxford: Blackwell, 2nd rev. edn, 1965 [1952]), pp. 63-93.

[6]. It is probably worthwhile to note at this point my policy on rabbinic literature lest I be accused, like Torrey (Rowley, ‘Suffering Servant’, pp. 76-77), of importing rabbinic interpretations into pre-rabbinic texts. It will be found that I employ rabbinic literature, as I do modern scholarship, only to confirm interpretations already reached from within the primary text, not as primary evidence itself. Similarly I cite rabbinic interpretations as supporting evidence that certain symbols were read as I suggest; or to show the persistence of certain biblical traditions into post-biblical times.

[7]. There is theoretically a third option, that the white bull is simultaneously a nagar. But this differs little from the first option since both involve dual states of being, which are perhaps more likely to be manifested serially than simultaneously. To my knowledge this interpretation has not been proposed.

[8]. Those who see the second beast as the first transformed include Dillmann, Das Buch Henoch, p. 287; Martin, Le livre d’Hénoch, p. 235n.; Milik, Books of Enoch, p. 45, who sees the transformation as signifying the bull’s increased power; perhaps Tiller, A Commentary, p. 388. Knibb, M.A. Knibb, Ethiopic Book of Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), II, p. 216, accepts that both one animal transformed or two separate animals are possible.

[9]. Torrey, ‘Messiah, Son of Ephraim’, p. 267.

[10]. Sifrê on Deut. 33.16, §353; Yalk. on Deut. 33.16, §959. See too the midrashim in n. 4 above. Torrey’s view may derive from the singular notion of G.H. Dix, ‘The Messiah ben Joseph’, JTS 27 (1926), p. 132, that Gen. 49.10 was evidence that Ben Joseph would displace Ben David.

[11]. The lion symbol, deriving from Gen. 49.9, occurs at e.g. 1 Kgs 10.19-20; 2 Chron. 9.18-19; 4 Ezra 11.36-12.3; 12.31-34; Gen. R. 95.1; Exod. R. 1.16; Num. R. 14.1; Est. R. 7.11; Midr. Tanh. 11.3. The ass symbol, deriving from Zech. 9.9, occurs at e.g. Gen. R. 75.6; Eccl. R. 1.9.1. The lion and ass were, of course, prohibited for sacrifice (Lev. 1.2; Exod. 34.20; 13.13). The Judahite Messiah is however symbolized by a bull on one occasion, at T. Jos. 19.5. But there the tribes of Israel are together symbolized by twelve bulls, and the bull cannot therefore be regarded as the proper symbol of Ben David in that place.

[12]. Dillmann, Das Buch Henoch. Leipzig: Vogel, 1853: 288; J. Flemming, Das Buch Henoch (GCS 5; Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs, 1901) 140; Tiller, A Commentary on the Animal Apocalypse, 389. The same view would appear to be implied by the majority of commentators, who see the nagar as an animal. However Isaac, ‘1 Enoch’, 71, appears to envisage three states with two intervening metamorphoses.

[13]. See Bodenheimer, Animal and Man in Bible Lands (Leiden: Brill, 1960) 108, where a picture of the aurochs shows its upright horns. He states that in his time the aurochs, although pronounced extinct, was (like the tribes of Ephraim) rumoured to be alive in the mountain fastnesses of Kurdistan. More recently its demise has been confirmed, but attempts to resurrect it are afoot.

Its nearest living relative may be the ancient breed of white wild oxen in Chillingham Park, Northumberland, whose blood group, unique among European cattle, shows them to be direct descendants of the ox which roamed Britain before Roman importation of bos taurus. Like the aurochs their horns grow upward on top of the head and ancestral skulls testify that they were formerly of great size.

Bos primogenius (sometimes primogenitus) means of course ‘firstborn bull’. The name may have arisen from the Linnaean classifier’s confusion of the two animals in the Vulgate: Quasi primogeniti tauri pulchritudo eius cornua rinocerotis cornua illius.

[14]. Gen. R. s. 31; Midr. Pss. on 22.22; Yalq. Shim. on Ps. 22 (§ 688); Midr. Pss. on 92.11; Rashi on Ps. 22.22.

[15]. Dillman, Henoch, 287-88; Milik, Books of Enoch, 45.

[16]. Milik, Books of Enoch, 4, 214; M.E. Stone, ‘1 Enoch’ in Jewish Writings of the Second Temple Period (ed. M.E. Stone)(Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984) 395-406.397.

[17]. Lindars, ‘A Bull, a Lamb and a Word’, 484.

[18]. Num. 23.22; 24.8; Deut. 33.17; Job 39.9; lxx Ps. 21.22 (=mt 22.22 [21]); lxx Ps. 28.6 (=mt 29.6); lxx 91.11 (=mt 92.11 [10]). The only exception is Isa. 34.7, where it is rendered ‘adroi, that is, ‘large’ or ‘well-grown’ (bovids).

[19]. Dillman, Henoch, 287-88; Charles, Enoch, 258-59; Martin, Le livre d’Hénoch, 235n.; Milik, Books of Enoch, 45; Knibb, Ethiopic Book of Enoch, II, p. 216. Torrey also thinks the nagar is an aurochs, but reaches the conclusion by another route, suggesting the Greek translator read Aramaic ראימא rema as מאמרא word (‘Messiah the Son of Ephraim’, p. 267).

Charles later changed his view, following Goldschmidt, Das Buch Henoch (Berlin, 1982), p. 90, to nagar as ‘lamb’, from a misreading of Hebrew טלה lamb as מלה word (The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913], p. 260; The Book of Enoch [London: SPCK, 1929], p. 128). But a Hebrew text of Enoch is unattested and the argument does not hold in Aramaic.

Lindars, ‘A Bull, a Lamb and a Word’, p. 485, suggested Aramaic אִמַּר lamb was read as אֵמַר word; but, he admits, such a spelling of אֵימַר is unattested, and it is rare even plene (only Tg. Num. 24.3, 15). Moreover a lamb is not a ‘great beast’ with ‘great black horns on its head’. Isaac feels it is better to refrain from emendation and take nagar as ‘word’ (‘1 Enoch’, p. 71).

Certainly ‘word’ is attested as a messianic term in later Israelite literature (Jn 1.1, 14). But the Johannine term is invariably translated with Ethiopic qāl, not nagar. Moreover a word, like a lamb, is not a great black-horned beast.

[20]. English has no singular non-gendered word for one beast of the domestic cattle. Bull indicates gender rather than species, and applies to animals other than cattle, such as elephants and antelope. Ox is too broad, since it can be applied also to the wild ox. Hebrew shor is a domestic bovid of either sex.

[21]. Num. 18.17; cf. Exod. 13.12, 15; Lev. 27.26; Deut. 12.17; 14.23; Exod. 13.2; Num. 3.13.

[22]. Bodenheimer, Animal and Man, 108, also notes the ferocity of the aurochs. The oxen of Chillingham Park, noted above, share the aurochs’ extreme ferocity and are quite unapproachable.

[23]. As with Latin cornus and corona, so Hebrew qrn supports a complex image-cluster symbolizing kingship (Ps. 148.14), anointing (1 Sam. 16.1), and radiance (Exod. 34.29-35).

[24]. Ancient near eastern prisons were underground dungeons, and so there developed a widespread association between imprisonment and death (see O. Keel, The Symbolism of the Biblical World [London: SPCK, 1978]). Cf. Isa. 24.22; 42.7, 22; Jer. 37.16; 38.6; Zech. 9.11.

[25]. Gen. R. 75.12; 86.3; 95.1; 95 (msv); 99.2; Exod. R. 1.16; 30.7; Est. R. 7.11; Lam. R. on 2.3 §6; Midr. Tan. Wayyigash (Gen. 44.18), §11.3 (Buber 102b/204).

[26]. Isaac’s acquisition of primogeniture is well-known (Gen. 27). Joseph was Rachel’s firstborn, but not Jacob’s. However, 1 Chron. 5.1-2 says Joseph was granted the rights of Jacob’s firstborn in place of disgraced Reuben. In this, the Chronicler draws only on what is implicit in Genesis, where Joseph is not only honoured above his brothers (Gen. 37.2, 3, 14), but receives the firstborn’s double portion (Gen. 48.22), by which his sons Ephraim and Manasseh each become tribes of Israel in their own right with their own inheritance (Josh. 14.4; 17.17-18). Ephraim, like his father, becomes an honorary firstborn when his grandfather Jacob again bestows pre-eminence on a lesser son (Gen. 48.13-20). Joseph, like his father, adopts his grandson as his direct heir (Gen. 50.23).

[27]. Similar usages elsewhere support this conclusion. At Num. 18.17 the firstborn of a shor is the offspring of the shor; two beasts. At Deut. 15.19-20 the firstborn of your shor is the offspring of the shor of the owner; three individuals, as here in Deut. 33.17.

[28]. E.G. Hirsch, ‘Joshua’, in JE,VII, p. 282. Bible verses such as Prov. 8.15; 27.18; 29.23 are applied to him (Num. R. §12-13).

[29]. Joshua was a descendant of the only princely line of Ephraim, and of the tribal leader Elishama ben Ammihud (1 Chron. 7.20-27; Num. 2.18; 7.48). Exod. 24.13; 33.11; Num. 11.28; 27.18-23; Josh. 1.16-18; 4.14. At Tg. Ps.-J. to Exod. 40.11 he is ‘the head of the sanhedrin of his people’.

[30]. Gen. R. 6.9 (shor, rem); 39.11 (shor, rem); 75.12 (firstborn shor); Num. R. 2.7 (shor); 20.4 (shor, rem: Israel under Joshua’s command).

[31]. H.L. Strack and P. Billerbeck, Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud und Midrasch (Munich, 1924/1928), II, p. 293.

[32]. Tg Ps.-Jon. to Exod. 40.11. The meturgeman clearly did not hold the belief, mentioned by Hirsch (‘Joshua’, pp. 282-83) and advanced by Strack and Billerbeek (Kommentar, II, p. 296) against Messiah ben Ephraim’s Joshuanic descent, that Joshua married Rahab and died without male issue. But the proof-texts cited in JE for this idea (Zeb. 116b; Meg. 14a; Yalq., Josh. §9) do not support the claim, while Yalq. Josh. §9 makes Rahab the ancestress of the Judahites of 1 Chron. 4.21. Joshua’s male issue seem also to be implied at AZ 25a, where the filling of the nations by Ephraim’s seed (Gen. 48.19) is said to have taken place at Joshua’s conquest of the land (Josh. 10.3).

[33]. Midr. Tan. Wayyigash (Gen. 44.18), §11.3 (Buber, 103) (firstborn shor); Gen. R. 75.6 (firstborn shor); Gen. R. 95 (msv); 99.2 (firstborn shor, rem); Pir. R. Eliez. 22a.ii: (firstborn shor, rem); Aggadat Bereshit 79 (firstborn shor, rem); Num. R. 14.1 (firstborn shor); Zohar, Mishpatim, 479, 481, 483 (shor); Pinhas, 565 (firstborn shor); 567 (shor); 745 (firstborn shor); Ki Tetze, 21 (shor, firstborn shor); 62 (shor). It is applied to Messiah in general at Pes. R. 53.2.

[34]. Otot 6.5; at Ag. M. 17, 20; As. M. 4.13; Saadia, Kitab al amanat, 8.5 (Rosenblatt 1948: 301); Zohar, Vayyera, 478-80, he appears in Galilee, the territory of Ephraim. See too the latterday ingathering led by the children of Rachel at Sifrê on Deut. 33.16 (Pisqa 353); b. BB 123b; Gen. R. 73.7; 75.5; 97 (NV in Soncino edn); 99.2; PRE 19b.ii.

[35]. Texts which see Messiah ben Joseph’s death as an atonement include Suk. 52a; Pes. R. 36-37; Saadia, Kitab VIII.6 (Rosenblatt 1948: 304); Nist. R. Shim. b. Yoh. 23 (Mitchell, Message, p. 331); Alshekh, Marot ha-Zov’ot on Zech 12.10; Naphtali ben Asher Altschuler, Ayyalah Sheluhah (Cracow, 1593)on Isa. 53.4; Samuel b. Abraham Lañado, Keli Paz on Isa. 52.13; Shney Luhot ha-Berit (Fürth 1724, 299b), cited in German in S. Hurwitz, Die Gestalt des sterbenden Messias: Religionspsychologische Aspekte der jüdischen Apokalyptik (Studien aus dem C.G. Jung-Institut, 8; Zürich/Stuttgart, 1958), pp. 162-63.

[36]. For his resurrection, see e.g., Ag. M. 2.22; Otot 9.1; Sef. Z. 49-50; Aser. Mel. 4; Pir. M. 5.47-49; NRSY 34; Midrash Wayyosha 15.18 (BHM I.35-57); Saadia, Kitab, 8.6; PRY (BHM VI.115); Zohar,Shlakh Lekha, 136; Balaq, 342.

[37]. Of course he is not the first white bull, nor even the first one born – the righteous line from Adam are represented by white bulls (1 En. 85.3, 9; 89.1, 10, 11). But neither were the titular firstborns Jacob, Joseph and Ephraim the first of their species, or even of their families. Their primogeniture was one of pre-eminence.

[38]. So too Martin, Le livre d’Hénoch, p. 235n.

[39]. Lindars, ‘A Bull, a Lamb and a Word’, p. 485.

[40]. Rowley, ‘Suffering Servant’, pp. 76-77.

[41]. Gen. R. 99.2: ‘the War Messiah, who will be descended from Joseph’; Midr. Tan. I.103a (§11.3): ‘in the age to come a War Messiah is going to arise from Joseph’; Num. R. 14.1: ‘the War Messiah who comes from Ephraim’; Aggadat bereshit, §63 (IV.87 in A. Jellinek, Bet ha-Midrash [= BHM], Jerusalem: Wahrmann, 1967 [Leipzig: Vollrath, 1853–77]): ‘a War Messiah will arise from Joseph’; Kuntres Acharon §20 to Yalkut Shimoni on the Pentateuch (BHM VI.79-90, p. 81): ‘a War Messiah is going to arise from Joseph’; Gen. R. 75.6; 99.2 applies Moses’ blessing on Joseph (Deut. 33.17) to the War Messiah.

The same conclusion is made by many commentators: Dalman, Der leidende, p. 6; L. Ginzberg, ‘Eine unbekannte jüdische Sekte’, Monatschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 58 (1914), p. 421; Strack and Billerbeck, Kommentar, p. 292; J. Heinemann, ‘The Messiah of Ephraim and the Premature Exodus of the Tribe of Ephraim’, HTR 68 (1975), pp. 1-15 (7); H. Freedman and M. Simon, The Midrash (London: Soncino, 1939), I, p. 698 n. 2; IX, p. 125 n. 3; M. Jastrow, A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Bavli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature (New York, 1950), p.852 (‘Mashiah’).

Strangely enough Knibb thinks the nagar is a War Messiah, whom he regards as a priestly figure (The Ethiopic Book of Enoch, II, p. 216). There are two passages where the mashuah milhamah is apparently a priest (m. Sot 8.1; Yoma 72b). But in eschatological contexts the reference is always to Messiah ben Joseph.

[42]. For Rowley’s views that there is no evidence linking Zech. 12.10 with Messiah ben Ephraim in pre-Christian times (‘Suffering Servant’, pp. 73-74), nor any linking the suffering servant of Isa. 53 with Messiah ben Ephraim (pp. 74-77), nor any that the death of Messiah ben Ephraim was ever thought of as vicarious (p. 76), see my ‘Messiah bar Ephraim in the Targums’ where the allegedly non-existent evidence is cited at length; see also n. 36 above.

[43]. For the necessity of Messiah ben Joseph’s descent from Joshua as well as from Joseph, see my ‘The Fourth Deliverer’, p. 552, and ‘Messiah bar Ephraim in the Targums’, where I present the genealogical and textual evidence for his Joshuanic descent.

It is worth noting at this point that the case has long been made for the existence in the Book of Similitudes (1 En. 37–71) of a transcendent heavenly figure with features of the mashiah of Ps. 2, the son of man of Dan. 7.13, and the servant of Yhwh of Isa. 49; 52.13–53.12. The literature on the subject is vast, but see, e.g., J. Jeremias, ‘Erlöser und Erlösung in Spätjudentum’, Deutsche Theologie (1929), pp. 109-15, who argues that 1 Enoch’s Son of Man (pp. 46-48, 62-63, 69-71) is equated with Isaiah’s servant and is exalted through death; more of the relevant literature is cited in Rowley, ‘Suffering Servant’, pp. 76-83.

[44]. There is a widespread view that Messiah ben Joseph developed out to the defeat of Bar Kokhba in 135 ce. See e.g., J. Hamburger, Realenzyklopädie des Judentums (Strelitz i. M., 1874), II, p. 768; J. Levy, ‘Mashiah’, Neuhebräisches und chaldäisches Wörterbuch (Leipzig 1876/1889), III, pp. 270-72; A. Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah (s.l. 1883), p. 79 n. 1, 434-435; Strack and Billerbeck, Kommentar, II, p. 294; J. Klausner, The Messianic Idea in Israel (London, 1956), pp. 487-92; Hurwitz, Die Gestalt des sterbenden Messias, pp. 178-80; G. Vermes, Jesus the Jew (London, 1973), pp. 139-40. Similarly Heinemann has suggested that an existing militant Ephraim Messiah became a dying messiah by analogy with Bar Kokhba (‘The Messiah of Ephraim’, pp. 1-15).

[45]. I have made the same point in Mitchell, ‘The Fourth Deliverer’, p. 553; ‘Rabbi Dosa’, pp. 89-90; ‘Messiah bar Ephraim in the Targums’. Similar views are found in J. Drummond, The Jewish Messiah (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1877), p. 357; A. Wünsche, Die Leiden des Messias (Leipzig, 1870), p. 110; D. Castelli, Il Messia secondo gli Ebrei (Florenz, 1874); G.H. Dalman, Der leidende und sterbende Messias der Synagoge (Berlin, 1888); Strack and Billerbeck, Kommentar, II, p. 293.

[46]. My caution comes from recognizing the possibility that Gen. 49.24 may be another source of the idea, and not from any doubt that Deut. 33.17 is itself a source.

[47]. J.C. O’Neill regards both these passages as essentially pre-Christian; see ‘The Lamb of God in the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs’, JSNT 2 (1979), pp. 2-30; ‘The Man from Heaven: SibOr 5.256-59’, JSP 9 (1991), pp. 87-102. J. Liver notes the considerable similarity in ideas, concepts and terminology between 1 Enoch, The Book of Jubilees, The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs and the Qumran literature, and suggests that they originated in closely related circles (‘The Doctrine of the Two Messiahs in Sectarian Literature in the Time of the Second Commonwealth’, HTR 52 [1959], pp. 149-85, 149).