THE SATOR SQUARE

THE SATOR SQUARE is an ancient “rebus” or word-square. Similar word-squares are known to us from ancient times. But, among them all, the SATOR square is an especially ingenious little construction. Yet more ingenious still is what is concealed within it. Once we decipher it, it will teach us something very significant about the earliest creeds of the Christian faith.

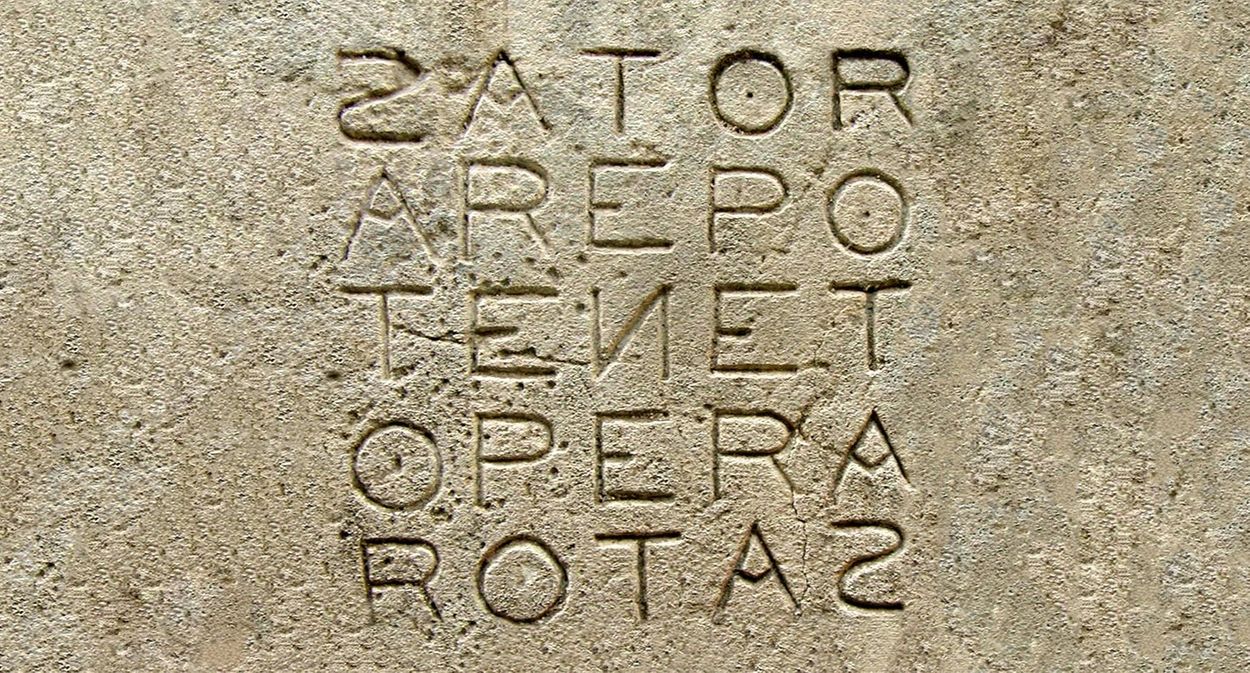

If we look carefully at the SATOR square, we will notice that it is a fourfold palindrome. That is, the sequence of its five words—SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS—can be read back-to-front in all four different directions, starting from top left downwards or rightwards and from bottom right upwards or leftwards.

What’s more, if a line is drawn from the top left S to the bottom right S, all the letters on either side of the line reflect one another in perfect symmetry. So too with a line running from top right to bottom left R.

It is also a multiple acrostic. That is, any letter in one word in the outer square is the first letter of another word running away at right angles to it.

ROMAN PERIOD ORIGINS

The SATOR square is ancient. In the second century AD, someone scratched it on a potsherd which ended up in a Manchester midden. Around the same time, it was engraved, more grandly, on a roof-tile of the villa publica of Aquincum—modern-day Budapest—the residence of the governor of the Roman province of Pannonia Inferior. In the third century, someone inscribed it on the walls of a Roman garrison in Dura-Europos, Syria, and a villa in Cirencester, England.

Later, in the fourth century, someone in Egypt wrote it on papyrus and wore it in an amulet around the neck. Then it appears in Italy, on an Abbey door, and in France, on an eighth-century Bible. In Norway it was written in runes. It even reached faraway Ethiopia, where it became the names of the five wounds of Jesus: SADOR, ALADOR, DANET, ADERA, RODAS. And, since medieval times, it has often appeared in books of charms and spells.

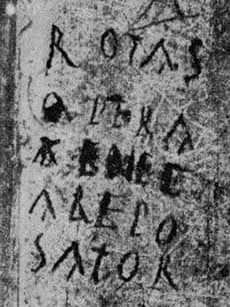

But interest in the SATOR square multiplied when archaeologists found three examples of it in the towns destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius. In Pompeii, they found one on a column beside the city’s Grand Palace. They found another on a wall in the house of Publio Paquio Proculo in Via Dell’ Abbondanza. And, in nearby Herculaneum, they found it etched on the pillar of a wrestling school. These finds showed that the SATOR square was already popular before August AD 79, the year when volcanic ash engulfed these cities and they lay undiscovered until the nineteenth century.

MEANING OF THE SATOR SQUARE

Any attempt to decipher the meaning of the square has to start with its five words—SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS. They are puzzling enough. At face value they mean, “Sower Arepo holds with labour the wheels.” But who is Arepo? And what are the wheels? Perhaps they were plough-wheels, for wheeled ploughs did exist in the first-century Roman empire.

If we ignore AREPO, a word unknown in any other Latin text, it might say, ‘He sows who works the [plough-]wheels.’ Or again, SATOR, ‘sower’, can mean progenitor or begetter. But the reader seeking a message in any of this may be forgiven for missing it.

A CROSS-SHAPED ‘TENET’ IN THE SATOR SQUARE

Yet puzzles have keys for their unlocking. And the key here is in the middle rows, in the two occurrences of the word TENET. These two words form a cross. But further, each of the Ts at the end of each TENET makes another cross. You see, Roman crosses took different forms. The crux immissa, the traditional Christian cross, had a protruding top point. The crux commissa, in the shape of a T, had no point. Nor was the Roman letter T always the same either. Some were written with, and some without, the protruding top point. So the Latin letter T, in whatever form, can be taken as a symbol for the cross. And so these crossed TENETs, each one with a cross at both ends, make it look like the SATOR square is a Christian device.

AN ICHTHUS FISH IN THE SATOR SQUARE

A Christian origin is further confirmed by the letter N in the middle of the cross. In Aramaic, the name of this letter, nun, carries the meaning of a ‘fish’. The fish, of course, was a Christian symbol from earliest times. Believers used it to secretly identify one another in times of persecution. One secret Christian might draw a curved line in the sand and the other would complete it with an intersecting curve to make the fish. In that way, they would identify themselves in times of persecution.

The fish-symbol came from the Greek word for fish, ichthus. Its five Greek letters—ιχθυς—form an acrostic for the early Christian creed: Iesous Christos theou uios soter: ‘Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour’. And the fish also served as a symbol for the members of the church, the great catch brought in by the Galilean fishermen who were sent as fishers of men.

Nobody knows when the Christian fish-symbol was first used. But, since the SATOR square and its TENET cross have the nun or ‘fish’ as their central letter, it looks like this is indeed an early use of the fish as a Christian symbol.

AN ABSOLUTE RULER IN THE SATOR SQUARE

Finally, the cross-shaped verb TENET, ‘he holds’, has its own meaning. The verb is used absolutely in Latin to refer to someone who holds supreme power in the state. Cicero, for instance, uses it in the plural form: ‘The aim of those who rule (qui tenent) is that nothing should remain’ (Ad Atticum 2:18). So, in the singular, as in the SATOR square, it means, ‘He rules.’

So the SATOR square looks very much like a Christian device. The central cross, with its cruciform Ts at each point, represents the cross of Christ. The central nun is the Aramaic word for the Christian fish-symbol and its credal statement that Jesus Christ is Son of God and Saviour. And the verb TENET looks like a statement that the one on the cross holds or rules the created order.

So we shouldn’t be surprised if people all across the Christian world thought the square had protective powers. Of course, in medieval Europe the Aramaic nun and the Greek creed would have been lost on most people. Yet the cross-shaped TENET alone was clear enough to anyone with a smattering of Latin. It told how the cross was linked with the ‘holding’ power of God who rules all things.

DIG A LITTLE DEEPER

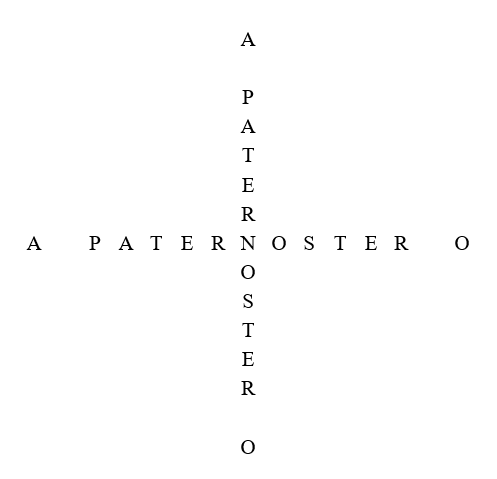

Between 1924 and 1927, scholars found that the square can be unrolled into a cross-shaped PATERNOSTER or ‘Our Father’ with a pair of extra As and Os, representing the Greek letters Alpha and Omega.[1]

The Alpha and Omega can be added before and after PATERNOSTER, perhaps depicting the eternity of the Father.

Or, maybe better still, the Alpha and Omega can be placed within the arms of the cross, to represent a Greek chi (Χ) for Christos superimposed upon the cross.

Now this discovery, of course, makes it even clearer that the SATOR square is an early Christian device. And it shows several things about what its maker believed.

PATER NOSTER, ‘Our Father’, is the Latin opening of the prayer that Jesus taught his disciples in Matthew 6:9–13 and Luke 11:2–4. In English, we call it ‘the Lord’s prayer’. But in most languages it is known simply by its opening words. The French call it the Notre père and the Germans, the Vater unser. In the same way, the Latin church called it the Paternoster. So this one word, PATERNOSTER, elicits the entire prayer. And that prayer is a summary, a manual, a vademecum, for the Christian faith.

Now in that prayer, ‘Our Father’ is the divinity whom we address in heaven. But, in the SATOR square, ‘Our Father’ is himself in a cross-shape. And it seems to me that we can see this in several ways.

A MAN ON THE CROSS

First, a man is on the cross. The Aramaic nun-fish at the centre tells us that he is ‘Jesus Christ, son of God, Saviour’. But ‘Our Father’ is there with him. ‘He holds’ (TENET) the man on the cross so that the sufferer, who calls on ‘Our Father’ will ultimately be saved from his sufferings. In that sense, ‘Our Father’ is, as it were, fully behind the cross. He not only upholds the sufferer, but as the Sower of all things, the cross is part of his will and plan.

OUR FATHER ON THE CROSS

Second, ‘Our Father’, PATERNOSTER, is also on the cross, but at his heart is the nun-fish representing Jesus. The composer of the SATOR square was well aware, of course, of the teaching about the Father, Son, and Spirit. It dates from apostolic times (Matt. 28:19; 2 Cor. 13:13; 1 Pet. 1:2). But he was a pre-Nicene Christian, living before the history of trinitarian disputes. A later age might suspect him of Modalism which fails to distinguish between the Persons of the Trinity, or even of Patripassianism, which sees the Father suffering in the bodily sufferings of the Son. Yet to completely deny the sufferings of the Father is an over-reaction. As Moltmann says, ‘The Son suffers and dies on the cross. The Father suffers with him, but not in the same way.’[2]

So our square-designer was no mean theologian. In fact, he has the highest possible Christology. He believed that God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself (2 Cor. 5:19). He closely identifies the one on the cross with the divine Father. He has no doubts at all about the divine nature of Jesus.

ALPHA AND OMEGA

Alpha and Omega are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. The writer of the Book of Revelation uses them as a title to signify the eternity of God Almighty (1:8; 21:6) and of Jesus (22:13; cf. 1:17). Now, my view is that the Revelation may date from around the time of Nero’s persecution in AD 64. And this suggests to me that the writer of the SATOR square knew the Book of Revelation. Of course, others date the Revelation from the late first century. And it’s possible one way or another that the Alpha-Omega of the SATOR square came first and the Revelation borrowed it. Either way is possible. After all, the Lord had said to Isaiah a full eight hundred years before, I am the first and I am the last (Isa. 44:6).

So, all in all, the SATOR square not only shows knowledge of the Lord’s Prayer and of the ‘Alpha and Omega’ title. But it also shows a Christology as high as any in the New Testament. It identifies the crucified Jesus with the Father, the Sower or Progenitor of all, who holds steady the wheels of all creation. It’s quite a message to be contained in a twenty-five letter puzzle.

ORIGINS OF THE SATOR SQUARE

Because the SATOR square was found amidst Vesuvian ash, we know it certainly existed in AD 79. Yet the Vesuvian squares cannot be the originals. Pompeii and Herculaneum were port cities, not centres of culture. There must have have been an older source from which these squares, and those in Manchester, Hungary, and Syria, all derived.

How old this source would have to be to reach Pompeii before AD 79 is open to question. But it is evidently the work of an erudite mind, well-versed in the teachings of the early church, and acquainted with Aramaic, Greek, and Latin. And, since the body of the text is in Latin, its source must lie in early Roman Christianity. It is therefore likely that it came from Rome, the centre of the early Latin church.

WHO WROTE IT, AND WHEN, AND WHY?

If we allow between fifteen and twenty years from its creation till its arrival in provincial Pompeii, then it must date from apostolic times, possibly from Nero’s persecution of AD 64. Since its composer was an Aramaic speaker, it could have been written by Simon Peter, or by Paul under house arrest, or by John Mark, or by Joseph Barsabas, or the eloquent Apollos. Or, of course, by another Aramaic speaker in Rome at that time.

As for the purpose of its creation, its author wrote it not simply as a statement of Christian faith, but also as an amulet for divine protection, a Christian mezuzah to be written on doors and walls, just as it was found in Pompeii and elsewhere later. For the church needed divine protection in the time of Nero’s fiery persecution. Coded messages became essential. To identify one another, Christians had the fish-symbol, or they spilled a little wine to represent the shed blood of Christ. In such a setting, a mysterious word-square, incomprehensible to the uninitiated, but eliciting the keeping power of God, the sacrifice of the divine man, and the Lord’s prayer, was the perfect amulet to etch on a wall or door.

If you’d like to know more about what the Lord’s Prayer can do for you and your family in your day to day life, then you might just like this book, How To Be Happy For Ever (No, Really!!).

Who knows, maybe it will turn your life around.

OBJECTION, YOUR HONOUR

Yet some object that the square is not Christian at all. Starting from the premiss that there could be no Christians in Pompeii in AD 79, or that the Christology of this text is way too high for the first-century church, they claim the text is Jewish or Mithraic.

But consider. If the square is not Christian, then the Paternoster and double Alpha-Omega are accidental. Yet the random chance of there being exactly the right 25 letters to make up these words from the 23 letters of the Latin alphabet is equivalent to 2325. That is, a chance of more than one in eleven decillion. Or, to be precise:

2325 = 11,045,767,571,919,545,466,173,812,409,689,943.

Such a number exceeds the estimated number of stars in the entire universe. If anyone wants to base their ideas on such odds, I wish them well. But me, I prefer the obvious solution.

Could it be Jewish? Even at face value, this square has a TENET cross right in the middle of it. And the cruciform T begins and ends each TENET. That, as explained above, is a declaration that the one on the cross, or the one who planned it, holds absolute power. What Pharisee would ever produce such a text? If this text is Jewish, then it is by a Jew who knew the Lord’s prayer, who enjoyed cruciform word patterns, and saw the cross as a manifestation of the divine glory of the Father and Sower of all. But then there were such Jews in Rome. They called themselves Christians.

Interested in the origins of the Christian faith? See Jesus: The Incarnation of the Word (2021).

CONCLUSION

So the SATOR square shows that, before 79 AD, some people saw the crucified Jesus as the one who holds absolute power, a divine man, one with the Father; that his prayer, the Our Father, is crucial to the Christian faith; that the cross was a Christian symbol; that the fish was also a Christian symbol, with its implied credal formula about Jesus the Saviour being the Son of God; and that Alpha and Omega was a title for Jesus and the Father, perhaps before the Revelation was written.

A few decades ago, such claims might have been seen as extreme. But there is now increasing consensus that the gospels were indeed written by the apostles and date from within a generation of Jesus’s lifetime.[3] So this reading of the SATOR square is hardly implausible.

Want to know more about how the earliest Christian communities used and understood the Lord’s Prayer? If so, see my blog on the The Lord’s Prayer in Aramaic. You might also like Praying the Lord’s Prayer.

[1] The encoded PATERNOSTER was found, apparently independently, by Hickes, ‘Roman Square’; Frank, Deutsche Gaue; Grosser, ‘Sator Formel’; Agrell, ‘Talmystik’.

[2] Moltmann, Crucified God, 203.

[3] Thiede and D’Ancona, Eyewitness; Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses.