WHY DO THE SCOTS LOVE UNICORNS?

THE SCOTS love unicorns. Well, who wouldn’t? But the Scots love them more than anyone else. Everyone is talking about it: the BBC, the National Geographic, and the Daily Mail. And, yes, unicorns are everywhere in Scotland. It’s nothing new. You see, the Scots have always loved unicorns, ever since ancient times. But the big question is Why Do The Scots Love Unicorns? Want to know more a bit more? Read on, McDuff…

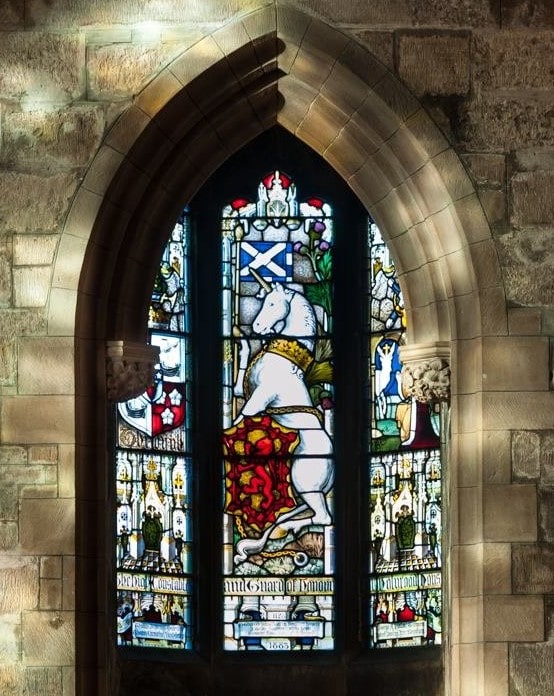

All over Scotland you’ll find them. Bold heraldic unicorns, wreathed in golden chains, adorn the gates and battlements of Caledonia’s castles and manors. Unicorns, fierce and frowning, gaze down from the great gateposts of Holyrood Palace or caper on heraldic shields in Craigmillar Castle. Unicorns, proudly holding the blue-and-white saltire flag of Saint Andrew, keep a watchful over the commerce of old Scotia’s burghers at the Mercat Crosses—the town market places—of Aberdeen, Dundee, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Inverness, Perth, Stirling, and a dozen other towns. You’ll find them in gold, bronze, ivory, granite, marble, and sandstone. You’ll find them on the figurehead of the royal frigate in Dundee. You’ll even find them in stained glass inside Saint Giles Cathedral on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. They’re everywhere. Scotland is unicorn-land.

THE SCOTS ALWAYS LOVED UNICORNS

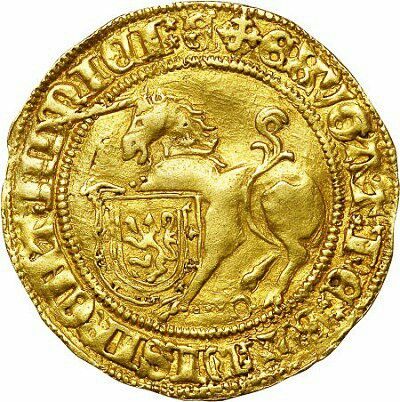

Nor is this a recent phenomenon. The unicorn has been an important national symbol as long as the Scots have been a people. Way back in the 1100s, William I of Scotland had a Scots love for unicorns. He had one emblazoned on his coat of arms. Unicorns flew on Scottish banners in the days when the Scots battled the English at Stirling Bridge and Bannockburn. A little later, Robert III featured it on the royal seal of Scotland. In the 15th century, it pranced on a Scots gold coin, called (you guessed it) the Unicorn. Before the Union of the Crowns, the Scottish coat of arms was flanked by two unicorns. You can see that in the coat-of-arms of Mary Queen of Scots, here at right. That was the traditional old coat-of-arms of Scotland.

In fact, when Queen Mary came from France to become queen of Scotland, she even brought a piece of unicorn horn with her. (No, really!) Nor was it just for decoration. Oh no! It was for sticking in her food before she ate, so that the unicorn horn would alert her immediately if her food had been poisoned by her enemies.

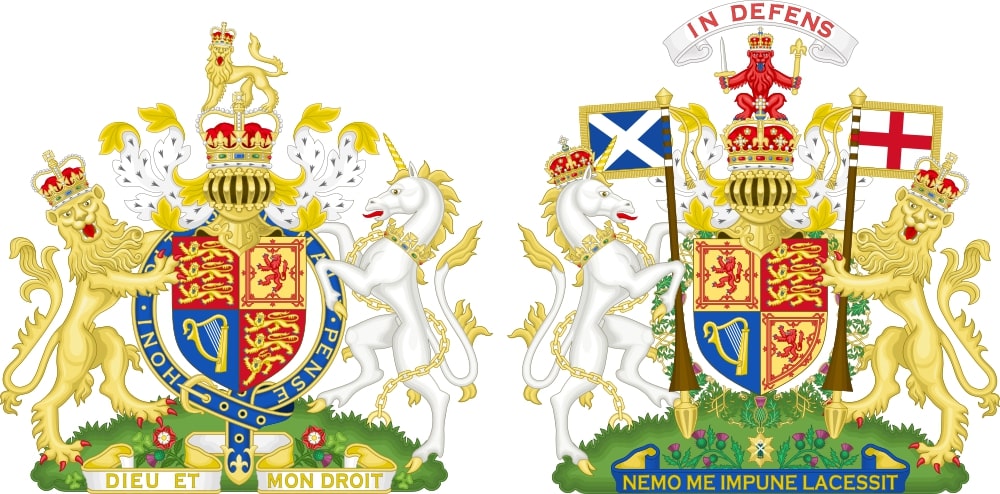

Of course, the lion had (and still has) an important role in Scottish heraldry. But after Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland (James I of England), inherited the English crown in 1603, and took his whole court to London, it was the Scottish unicorn, not the Scottish lion, which joined the English lion on the royal coat of arms.

You can see that in the picture below, in the picture on the right. In fact, there are now two versions of the British coat-of-arms. In the English version, at left, the lion is crowned but the unicorn is not. I wonder why? But the Scottish version, at right, has a crowned unicorn, with the ancient Scottish motto, “Nemo me impune lacessit”, colloquially rendered in Scotland as the words of the thistle: “Wha daur meddle wi’ me?” (“Who dare meddle with me?”)

When James came to set up his court in London, he was not too popular with his English subjects. They celebrated Scots rule in a couplet:

Hark, hark, the dogs do bark,

The beggars have come to town.

In fact, that’s what Guy Fawkes’s Gunpowder Plot was all about. He detested the idea that a Scot was sitting on the English throne and wanted to blow James “back to his Scottish hills”. The Londoners even wrote a song to tell how the lion bested the unicorn.

The lion and the unicorn

Were fighting for the crown

The lion beat the unicorn

All around the town.

Some gave them white bread,

And some gave them brown;

Some gave them plum cake

and drummed them out of town.

Unfortunately for the Londoners, their dream of drumming out the Scots remained a dream. The Stewart seed remained on the throne until they were replaced by German Georg, fifty-third in line for the throne, in 1714. (Like that was better! At least the Stewarts could speak English.)

THE SCOTS UNICORN IN THE ZOO OF NATIONS

These days, many nations have an animal symbol. England, Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, and not a few others, have the lion. America, Austria, Belgium, and Russia have the eagle. Bengal has the tiger, China the panda, and Australia the kangaroo. But these are all real animals which you can find in the real world. The Scots alone remain obstinately devoted to a mythological beast not found within their borders, nor anyone else’s.

Now all of this is well known. But the real question, the question which nobody seems to be able answer, is, “Why Do The Scots Love Unicorns?” The unicorn, they say, is a symbol of purity, or of power. But there’s much more to it than that. The real truth is that the unicorn has long been associated with the most ancient claims of Scottish identity. Let’s look into this a bit further.

THE AUROCHS OF THE HOUSE OF EPHRAIM

The unicorn is a symbol of the Scots’ claim to be descended from the twelve tribes of Israel and, in particular, from the House of Ephraim, who were the offspring of the Patriarch Joseph—Joseph of the marvellous dreams and the coat of many colours—who was Prince of Egypt almost four thousand years ago.

The story begins in Genesis 49. Jacob, the father of the Israelites, on his deathbed, made prophecies concerning his sons. I won’t go into all the details here. But he apportioned animal symbols to some of his sons. Lordly Judah he called the lion’s cub, Issachar the brawny ass, Dan the serpent, Naphtali the gazelle, and Benjamin the wolf. Yet, although Jacob loved Joseph best of all his sons, and gave him the longest and most bountiful of all his blessings, he didn’t give Joseph or his sons an animal symbol to stand beside the others.

Then, some four hundred years later, Moses became Israel’s leader. By this time the sons of Joseph had become two great clans, Ephraim and Manasseh. Like Jacob, Moses spoke a blessing on the tribes of Israel before his death. You can find it in Deuteronomy 33. Like Jacob, he spoke an exceptionally long and rich blessing over Joseph’s tribes. And, since Joseph had waited so long for an animal symbol to stand beside the others, Moses now gave him not just one, but two related animals. The key part of the blessing goes like this:

13. And of Joseph he said…

17. The firstborn of his shor is his majesty,

and the horns of a rem are his horns.

With them he shall gore the nations, all as one,

even to the ends of the earth.

18. And these are the ten thousands of Ephraim;

and these are the thousands of Manasseh.

Now here Moses compares the tribe of Joseph to two different kinds of bovid, namely, the shor and the rem (or r’em). They are both bulls. And so, in general, Joseph’s symbol became the bull.

FIRSTBORN SHOR & REM

Now, it’s fair to say that the shor and the rem are very different beasts. The shor is the bos taurus or domestic ox. It is a bearer of burdens, a captive and a slave. But Joseph’s shor is not just any shor. It is the ‘firstborn of a shor’, which, in Israelite law, was distinguished from its siblings by two things. The upside was that it was exempt from the hard labour which was the lot of other oxen, as it says in Deuteronomy 15.19: You shall not do work with the firstborn of your shor. The downside was that it was born under sentence of a violent sacrificial death, as we read in Numbers 18.17: The firstborn of a shor you shall not redeem; they are holy. Sprinkle their blood upon the altar. It was a bloody business being a firstborn shor.

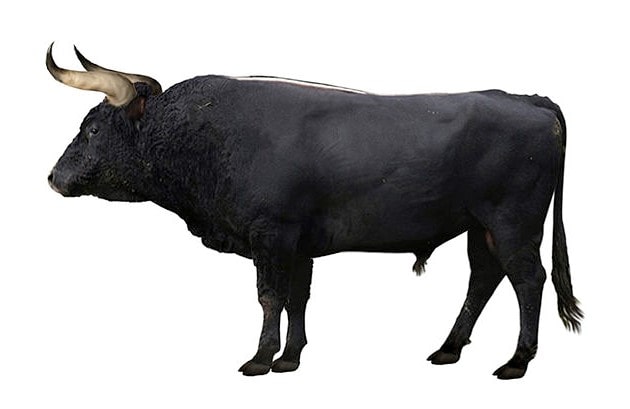

But the rem, on the other hand, is the bos primigenius or aurochs, the Eurasian wild ox. The aurochs is now extinct. The last European aurochs died as late as 1627, in Poland. But its brothers in the Levant died out more than 2,000 years before, during the Levantine Iron Age (1200–600 BC), as a result of human competition for pasture-lands. Yet, to those who knew it, when it roamed freely throughout West Asia, Europe, and North Africa, the aurochs was a truly fearsome beast. Aurochs skeletons have been found standing two metres tall at the shoulder, with the tips of the great black horns rising three metres from the ground.

Julius Caesar saw the European aurochs during his campaign in Germany’s Black Forest. He described it as follows:

They are only a little smaller than elephants, and have the appearance, colour, and shape of a bull. Their strength is very great, and also their speed. They spare neither man nor beast that they see. They cannot be brought to endure the sight of men, nor be tamed, even when taken young. The size, shape, and appearance of their horns differ much from the horns of our oxen (Gallic War, VI.28).

All were in awe of this monstrous creature. From Neolithic Lascaux to Babylon’s Ishtar gate, it ramped and roared its way through the iconography of the ancient world.

So there is a total contrast between the firstborn of a shor and a rem. What one is, the other is not. One is lowly and bound to slaughter. The other is sovereign and bound to life. And the reason why Joseph is compared to these two very different bulls is that it reflects the servitude and mortification he endured before being raised to glory and honour. And, in the same way, it presages that the Messiah, whom Jacob promised to Joseph, would die as a sacrifice before rising to rule. If you want to know more about that, then see my post on Messiah ben Joseph.

THE REM BECOMES THE MONOKEROS

But back to unicorns. The ancient Hebrew text made Joseph’s symbol to be the bull, more precisely, the shor (שור) and rem (ראם). Then, in the third century BC, the Bible appeared in a language the rest of the world could understand when the ancient Greek translation (called the Septuagint) was made by Jewish scholars in Alexandria in Egypt. The Septuagint translators had no difficulty translating shor. Everyone knew what a domestic ox was. They trudged up and down the banks of the Nile.

But the rem was not so easy to identify. Remember, it had been extinct in the Levant and North Africa since at least 600 BC, that is, four hundred years before the Septuagint translators did their work. So they had never seen one. Nor did they know what kind of beast it was, although it was clear from Deuteronomy, and from all the other places where the rem is mentioned in the Bible, that it was a wild animal, much bigger and stronger and tougher than a shor.

So the closest thing the Septuagint translators could imagine was a very big, strong, horned quadruped which lived to the south, in the lands of the Sudan. They called it the monokeros or ‘one-horn’ or the rhinokeros or ‘nose-horn’, which is pretty much the same thing. The Septuagint translators had probably seen this beast, for exotic animals were traded from Africa up to the Hellenistic world, passing through Alexandria on the way. So, when confronted with the Bible’s memories of a big, strong quadruped called the rem, the Septuagint translators decided it was the monokeros. Nor were they deterred by thinking that a monokeros could not have ‘the horns [plural] of a rem’. After all, the African monokeros did indeed have two horns, both substantial.

THE MONOKEROS BECOMES THE UNICORN

And so, in the hands of the Septuagint translators, Joseph’s symbol changed from the rem or aurochs to the monokeros. In time, the Latin Vulgate translation, in the fourth century AD, followed the Septuagint, calling Joseph’s great beast the rinoceros. Of course, the Vulgate became the only Bible of medieval western Europe where, in popular usage, the beast came to be known by the Latin form of its name, unicornus.

Yet, in medieval Europe, no-one had ever seen a monkeros or rinoceros or indeed an unicornus of any kind. All they knew was that it was a large quadruped with, as its name suggested, one horn. The largest quadruped they could conceive of was a horse. And so the unicorn became, in the medieval imagination, a fabulous horse-like beast, sometimes with the hindquarters or feet of a lion.

Remarkable fables grew up about the unicorn. Isidore, the learned 7th century Archbishop of Seville, preached to the faithful that: “The unicorn is too strong to be caught by hunters, except by a trick: if a virgin is placed in front of a unicorn and she bares her breast to it, all of its fierceness will cease and it will lay its head on her bosom, and thus quieted is easily caught.” Good to know.

And so, in this way, Joseph’s triumphant bull metamorphosed from aurochs to monokeros to a fabulous one-horned shining horse with a soft spot for maidens. But what did all this have to do with the Scots and their love of unicorns?

WHY DO THE SCOTS LOVE UNICORNS?

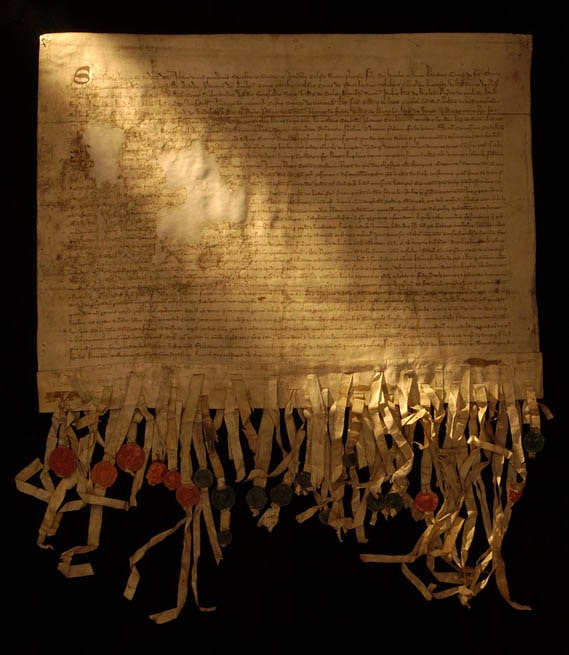

To explain why the Scots love unicorns—why they identify with unicorns—we must now turn to an ancient Scottish document, the Declaration of Arbroath.

In the 1290s, King Edward I of England, was invited to arbitrate in the Scottish Royal succession. Around the same time he came to pay respects at the new Cathedral built over the shrine of St Mungo. He brought with him, as an offering, large quantities of timber for the Cathedral roof. But when his appointee to the crown, John Balliol, was deposed by the Scottish lords, Edward launched a bloody campaign of conquest against the Scots. Bishop Robert Wishart of Glasgow took Edward’s timber to construct siege engines against the English invaders.

The English campaign was prolonged and cruel and was continued by Edward II. The Scots sought a way to cut if off at source by appealing to Pope John XXII. And so the Declaration of Arbroath was written in 1320, probably by Bernard de Linton, the Abbot of Arbroath and Chancellor of Scotland, at the behest of the Scottish nobles. Its purpose was to justify the independence of the Scottish nation in the face of English claims that they had received the gospel before the Scots, and so, being the more ancient Christian nation, had the right to rule Scotland.

THE DECLARATION OF ARBROATH

The Declaration of Arbroath is justly famous. First, as a plea for independent nationhood as the will of the people and their leaders it has few parallels in history. The Scots, it says, are determined to live as a free nation no matter what the English or Rome might send against them. It eloquently declares that they are prepared to lay down their lives for their national freedom.

For as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom—for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

But further, the Declaration of Arbroath flatly denied the ideology that held sway throughout Europe and, indeed, much of the world, the ideology of the divine right of kings. It stated that, although the people were bound to the king “both by law and by his merits”, this allegiance was based on the premiss that he would defend them and uphold their freedom and rights. If he failed in this expectation, the people would replace him with another. In this idea, that rulers rule by consent, the Declaration of Arbroath directly influenced both the Reformation and the American Declaration of Independence.

Yet, what concerns us here is the part of the document that follows after the opening preamble of greetings and the list of signatories. Its purpose was to counter the claim that the English were the more ancient Christian nation. But it says much more about how the Scots views themselves. It runs as follows:

Most Holy Father and Lord, we know, and from the chronicles and books of the ancients we find, that among other famous nations our own, the Scots, has been graced with widespread renown. For they journeyed from Greater Scythia by way of the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Pillars of Hercules, and dwelt for a long course of time in Spain among the most savage tribes, but nowhere could they be subdued by any race, however barbarous.

Thence they came, twelve hundred years after the people of Israel crossed the Red Sea, to their home in the west where they still live today. The Britons they first drove out, the Picts they utterly destroyed, and, even though very often assailed by the Norwegians, the Danes and the English, they took possession of that home with many victories and untold efforts; and, as the historians of old time bear witness, they have held it free of all bondage ever since. In their kingdom there have reigned one hundred and thirteen kings of their own royal stock, the line unbroken by a single foreigner.

The high qualities and deserts of these people, were they not otherwise manifest, gain glory enough from this: that the King of kings and Lord of lords, our Lord Jesus Christ, after His Passion and Resurrection, called them, even though settled in the uttermost parts of the earth, almost the first to His most holy faith. Nor would He have them confirmed in that faith by merely anyone but by the first of His Apostles by calling—though second or third in rank—the most gentle Saint Andrew, the Blessed Peter’s brother, and desired him to keep them under his protection as their patron forever. See the full text of the Declaration…

In other words, the Declaration of Arbroath dates the beginnings of the Scottish people to when when the Israelites crossed the Red Sea. The implication, of course, is that the Scots are of Israelite descent. The Declaration then proceeds to speak of their sojourn in Greater Scythia, that is, in northern Persia and Afghanistan. This refers to the captivity of the tribes of Joseph, when, in 722 BC, Sennacherib’s Assyrian army invaded the northern kingdom of Israel (not the southern kingdom of Judah) and swept many Israelites of the House of Joseph into captivity, settling them “in Halah, in Gozan on the Habor River and in the towns of the Medes” (2 Kings 17:6), that is, in the area of Greater Scythia. Yet from there, the exiled Ephraimites spread out into many parts of the world.

The Declaration then tells how the Scots travelled through the Mediterranean, through the Pillars of Hercules—the Straits of Gibraltar—and dwelt many years in Spain, before they arrived in their northern land, 1200 years after the Exodus, that is, between 300 and 50 BC, depending on how one dates the Exodus. And then the Declaration goes on to speak of the Viking and English invasions.

So the Scottish answer to the Pope was this: The English are not a more ancient Christian nation than we. In fact, we are Israelites, the children of the scattered House of Joseph. We have dwelt in this land since before the time of Christ. And, by the way, Saint Andrew himself, the brother of your patron Peter, is our patron and guardian (for his bones were brought to Scotland in the 4th century by Saint Regulus).

THE POPE’S REPLY

Pope John—to his everlasting credit—was convinced by this argument. He immediately urged Edward II to make peace with the Scots. Not long after, in 1328, the English acknowledged Scotland as an independent nation.

But, as far as the Scots love of unicorns is concerned, the point beyond dispute is this: In the early 14th century, the Scots believed themselves to be descendants of the tribes of Joseph. And that explains why they took for themselves the symbol of Joseph’s great-horned beast which, by medieval times, had become the unicorn.

As for whether or not this Scots claim is true, much depends (as always) on who you ask. But, in my rather unbiased view, there are three things in its favour.

TRUE OR FALSE?

First, DNA evidence can neither prove nor disprove it. The best DNA evidence of Israelite descent—the celebrated Cohanim haplotype—derives from an Israelite male of the mid-first millennium BC. No-one has yet identified a haplotype to prove or disprove descent from the patriarchs.

Second, the historicity of the Ephraimite sojourn in Scythia and their subsequent diaspora is beyond dispute. The Judeo-Roman historian Josephus wrote, in the first century AD, that “the ten tribes are beyond the Euphrates till now, and are an immense multitude and not to be estimated in numbers” (Antiquities, 11.133) This great people-movement happened in fulfilment of Jacob’s prophecy over Ephraim, that “His seed shall fill the nations” (Gen. 48:19). The Scots are not the only nation that trace their descent from this dissemination. And it is possible that the name, Scots or Scotii, originated from their being identified by their neighbours as Scutii, that is Scythians.

Finally, remember, that this Scots’ claim is of some antiquity. This is not the silly British Israelitism of Herbert Armstrong, who foolishly insisted that British meant b’rit-ish (man of the covenant). No. It is an early 14th-century document. And it is addressed to no less a person than the Pope who, as the writers believed, would have been able to verify their claims. And so, while a number of nations claim Ephraimite descent, no other claim is as ancient or as weighty as this one. Yet it was made when Bibles were rare, and when any real knowledge of Israelite history was rarer still. But the professed itinerary is quite in keeping with what we now know of the captivity and dispersal of the Ephraimites.

So my humble opinion is that the Scots claim to be descendants of the tribes of Joseph, though unproven, is far from incredible. And, of course, it totally explains why the Scots love unicorns.

If you’d like to know more about the mighty aurochs and its place in Bible imagery and prophecy, I discuss it fully in Chapter 2 of Messiah ben Joseph.